|

Śrīla Prabhupāda Līlambṛta - — Śrīla Prabhupāda Līlambṛta

Volume I — A lifetime in preparation — Volumen I — Toda una vida en preparación

<< 4 How Shall I Serve You? >> — << 4 ¿Cómo debo servirte? >>

| “I have every hope that you can turn yourself into a very good English preacher if you serve the mission to inculcate the novel impression of Lord Caitanya’s teachings to the people in general as well as philosophers and religionists.”

— Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī in a letter to Śrīla Prabhupāda, December 1936

| | «Tengo todas las esperanzas de que puedas convertirte en un muy buen predicador en inglés si cumples la misión de inculcar la impresión novedosa de las enseñanzas del Señor Caitanya a la gente en general, así como a los filósofos y religiosos».

— Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī en una carta a Śrīla Prabhupāda, diciembre de 1936

|  | IN OCTOBER OF 1932, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī led a group of hundreds of disciples and pilgrims on a month-long parikrama, or circumambulation, of the sacred places of Vṛndāvana. Vṛndāvana residents and visitors perform parikrama by following the old, dry bed of the Yamunā River and circumambulating the Vṛndāvana area, stopping at the places where Kṛṣṇa performed His pastimes when He roamed in Vṛndāvana five thousand years ago. Abhay had wanted to attend Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī’s parikrama but couldn’t because of his work. Nevertheless, on the twentieth day of the pilgrimage he traveled from Allahabad, intent on seeing Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī again and hoping to join the parikrama party at Kosi, just outside Vṛndāvana, at least for a day.

| | EN OCTUBRE DE 1932, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī dirigió a un grupo de cientos de discípulos y peregrinos en un parikrama, o circunvalación de un mes de duración, en los lugares sagrados de Vṛndāvana. Los residentes y visitantes de Vṛndāvana realizan el parikrama siguiendo el lecho viejo y seco del río Yamunā y circunvalando el área de Vṛndāvana, deteniéndose en los lugares donde Kṛṣṇa realizó sus pasatiempos cuando vagó en Vṛndāvana hace cinco mil años. Abhay quiso asistir al parikrama de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī pero no pudo debido a su trabajo. Sin embargo, el vigésimo día de la peregrinación viajó desde Allahabad, con la intención de volver a ver a Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī y con la esperanza de unirse a la fiesta del parikrama en Kosi, a las afueras de Vṛndāvana por al menos un día.

|  | The parikrama Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta had organized was one of the biggest ever seen in Vṛndāvana. By engaging so many people, he was using the parikrama as a method of mass preaching. Even as early as 1918, when he had first begun his missionary work, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta’s specific contribution had been his emphasis on preaching. Prior to his advent, the Vaiṣṇavas had generally avoided populated places, and they had performed their worship in holy, secluded places like Vṛndāvana. Even when they had traveled to preach, they would maintain the simple mode of the impoverished mendicant. The Gosvāmī followers during Lord Caitanya’s time had lived in Vṛndāvana underneath trees; one night under one tree, the next night under another.

| | El parikrama que Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta había organizado fue uno de los más grandes jamás vistos en Vṛndāvana. Al involucrar a tanta gente, estaba usando el parikrama como método de predica masiva. Incluso en 1918, cuando había comenzado su trabajo misionero, la contribución específica de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta había sido su énfasis en la predica. Antes de su advenimiento, los vaiṣṇavas generalmente evitaban los lugares poblados y realizaban su adoración en lugares sagrados y apartados como Vṛndāvana. Incluso cuando viajaban para predicar, mantenían el modo sencillo del mendigo empobrecido. Los seguidores de los Gosvāmīs durante el tiempo del Señor Caitanya habían vivido en Vṛndāvana debajo de los árboles; una noche debajo de un árbol, la noche siguiente debajo de otro.

|  | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, whose aim was on preaching worldwide, knew that the renunciation of the Gosvāmīs was not possible for Westerners; therefore he wanted to introduce the idea that devotees could even live in a big palatial temple. He had accepted a large donation from a wealthy Vaiṣṇava merchant and in 1930 had constructed a large marble temple in the Baghbazar section of Calcutta. In the same year, he had moved, along with many followers, from his small rented quarters at Ultadanga to the impressive new headquarters.

| | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, cuyo objetivo era predicar en todo el mundo, sabía que la renuncia de los Gosvāmīs no era posible para los occidentales; por lo tanto, quería presentar la idea de que los devotos podrían incluso vivir en un gran templo palaciego. Aceptó una gran donación de un rico comerciante vaiṣṇava que en 1930 había construido un gran templo de mármol en la sección de Bagdad en Calcuta. En el mismo año se mudó junto con muchos seguidores, de sus pequeñas habitaciones alquiladas en Ultadanga a la impresionante nueva sede.

|  | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta was demonstrating that although a devotee should not spend a cent for his own sense gratification, he could spend millions of rupees for the service of Kṛṣṇa. While previously Vaiṣṇavas would not have had anything to do with the mechanized contrivances introduced by the British, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta, on the authority of scripture, was demonstrating a higher understanding. It was Rūpa Gosvāmī, the great disciple of Lord Caitanya, who had written, “One is perfectly detached from all materialistic worldly entanglement not when one gives up everything but when one employs everything for the service of the Supreme Personality of Godhead, Kṛṣṇa. This is understood to be perfect renunciation in yoga.” If everything is God’s energy, then why should anything be given up? If God is good, then His energy is also good; material things should not be used for one’s own sense enjoyment, but they could be and should be used for the service of Kṛṣṇa. So Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta wanted to use the most modern printing presses. He wanted to invite worldly people to hear kṛṣṇa-kathā in gorgeously built temples. And, for their preaching, devotees should not hesitate to ride in the best conveyances, wear sewn cloth, or live amidst material opulence.

| | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta estaba demostrando que aunque un devoto no debía gastar un centavo para su propia complacencia sensorial si podía gastar millones de rupias al servicio de Kṛṣṇa. Mientras que anteriormente los vaiṣṇavas no habían tenido nada que ver con los artilugios mecanizados introducidos por los británicos, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta, bajo la autoridad de las Escrituras, estaba demostrando un mayor entendimiento. Fue Rūpa Gosvāmī, el gran discípulo del Señor Caitanya, quien escribió: “Uno está perfectamente desapegado de todo enredo materialista del mundo, no cuando se renuncia a todo, sino cuando emplea todo para el servicio de la Suprema Personalidad de Dios, Kṛṣṇa. Esto se entiende en el yoga como renuncia perfecta". Si todo es la energía de Dios, ¿por qué se debe renunciar a algo? Si Dios es bueno, entonces su energía también es buena; las cosas materiales no deben usarse para el disfrute de los sentidos, pero pueden y deben usarse para el servicio de Kṛṣṇa. Entonces Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta quería usar las imprentas más modernas. Quería invitar a personas mundanas a escuchar kṛṣṇa-kathā en templos magníficamente construidos. Para realizar su prédica los devotos no deben dudar en viajar en los mejores medios de transporte, usar ropa cosida o vivir en medio de la opulencia material.

|  | It was in this spirit that he had constructed the building at Baghbazar and there displayed a theistic exhibition, a series of dioramas assembled from finely finished, painted, and dressed clay dolls. Such dolls are a traditional art form in Bengal, but the staging of nearly one hundred elaborate displays depicting the Vaiṣṇava philosophy and the pastimes of Lord Kṛṣṇa had never before been seen. The theistic exhibition created a sensation, and thousands attended it daily.

| | Fue con este espíritu que construyó el edificio en Baghbazar, allí instaló una exposición teísta, una serie de dioramas ensamblados a partir de muñecos de arcilla finamente terminadas, pintados y vestidos. Tales muñecos son una forma de arte tradicional en Bengala, pero nunca se había visto la puesta en escena de casi cien exhibiciones elaboradas que representan la filosofía vaiṣṇava y los pasatiempos del Señor Kṛṣṇa. La exposición teísta creó una positiva sensación, miles asistieron diariamente.

|  | In that same year, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī had taken about forty disciples on a parikrama all over India, a tour featuring many public lectures and Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta’s meetings with important men. By 1932 he had three presses in different parts of India printing six journals in various Indian dialects.

| | En ese mismo año, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī había llevado a unos cuarenta discípulos a un parikrama por toda la India, una gira con muchas conferencias públicas y reuniones de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta con hombres importantes. Para 1932 tenía tres imprentas en diferentes partes de la India imprimiendo seis revistas en varios dialectos indios.

|  | In Calcutta a politician had asked Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī how he could possibly print his Nadiyā Prakāśa as a daily newspaper. Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī had replied that it was not so amazing if one considered that in Calcutta alone there were almost half a dozen ordinary daily newspapers, although Calcutta was but one city amongst all the cities of India, India was but one nation amongst many nations on the earth, the earth was but an insignificant planet amidst all the other planets in the universe, this universe was one amongst universes so numerous that each was like a single mustard seed in a big bag of mustard seeds, and the entire material creation was only one small fraction of the creation of God. Nadiyā Prakāśa was not printing the news of Calcutta or the earth but news from the unlimited spiritual sky, which is much greater than all the material worlds combined. So if the daily Calcutta newspapers could report limited earthly tidings, then small wonder that Nadiyā Prakāśa could appear daily. In fact, a newspaper about the spiritual world could be printed every moment, were there not a shortage of interested readers.

| | En Calcuta, un político le había preguntado a Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī cómo podía imprimir su Nadiyā Prakāśa como un diario. Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī respondió que no era tan sorprendente si uno consideraba que solo en Calcuta había casi media docena de periódicos diarios, aunque Calcuta era solo una ciudad entre todas las ciudades de India, India era solo una nación entre muchas naciones en la tierra, la tierra no era más que un planeta insignificante en medio de todos los otros planetas del universo, este universo era uno entre universos tan numerosos que cada uno era como una semilla de mostaza en una gran bolsa de semillas de mostaza, toda la creación material es solo una pequeña fracción de la creación de Dios. Nadiyā Prakāśa no estaba imprimiendo las noticias de Calcuta o la tierra, sino las noticias del ilimitado cielo espiritual, que es mucho mayor que todos los mundos materiales combinados. Si los periódicos diarios de Calcuta podían informar noticias terrenales limitadas, entonces no es de extrañar que Nadiyā Prakāśa pudiera aparecer diariamente. De hecho, un periódico sobre el mundo espiritual podría imprimirse en todo momento mientras no hubiera escasez de lectores interesados.

|  | One of Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta’s publications was in English, The Harmonist, and it advertised the Vṛndāvana parikrama of 1932.

| | Una de las publicaciones de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta era en inglés, El Armonista y anunció allí el parikrama de Vṛndāvana de 1932.

|  | Circumambulation of Sri Braja Mandal

| | Circunvalación del Mandal de Sri Braja

|  | His Divine Grace Paramahamsa Śrī Śrīmad Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Gosvāmī Maharaj, the spiritual head of the Madhva-Gauḍīya Vaishnava community, following Śrī Kṛṣṇa Caitanya Mahaprabhu, has been pleased to invite the co-operation of all persons of every nationality, irrespective of caste, creed, colour, age, or sex, in the devotional function of circumambulation of the holy sphere of Braja in the footsteps of the Supreme Lord Sri Kṛṣṇa Caitanya, Who exhibited the leela of performing the circumambulation of Śrī Braja Mandal during the winter of 1514 A.D.

| | Su Divina Gracia Paramahamsa Śrī Śrīmad Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Gosvāmī Maharaj, el jefe espiritual de la comunidad Madhva-Gauḍīya Vaishnava, siguiendo a Sri Kṛṣṇa Caitanya Mahaprabhu, se complace en invitar a la cooperación de todas las personas de todas las nacionalidades, independientemente de su casta, credo, color, edad o sexo, en la función devocional de la circunvalación de la esfera sagrada de Braja siguiendo los pasos del Señor Supremo Sri Kṛṣṇa Caitanya, quien exhibió el pasatiempo de realizar la circunvalación de Śrī Braja Mandal durante el invierno de 1514 d.C.

|  | When Abhay had heard from the members of the Allahabad Gauḍīya Maṭh about the parikrama, he had been fully occupied with his local Prayag Pharmacy business and traveling to secure new accounts. But he had calculated how he could join at least for a day or two, and he had fixed his mind on again obtaining the darśana of Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī.

| | Cuando Abhay se enteró de los miembros del Allahabad Gauḍīya Maṭh sobre el parikrama, estaba completamente ocupado con su negocio local de Farmacia Prayag y viajó para asegurar nuevos clientes. Calculó cómo podría unirse al menos durante un día o dos y decidió concentrarse nuevamente en obtener el darśana de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī.

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda: I was not initiated at the time of the parikrama, but I had very good admiration for these Gauḍīya Maṭh people. They were very kind to me, so I thought, “What are these people doing in this parikrama? Let me go.” So I met them at Kosi.

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda: No fui iniciado en el momento del parikrama, pero tenía una muy buena admiración por estas personas del Maṭh Gauḍīya. Fueron muy amables conmigo, así que pensé: “¿Qué están haciendo estas personas en este parikrama? Déjame ir..” Entonces los encontré en Kosi.

|  | The parikrama party traveled with efficient organization. An advance group, bringing all the bedding and tents, would go ahead to the next day’s location, where they would make camp and set up the kitchen. Meanwhile, the main party, bearing the Deity of Lord Caitanya Mahāprabhu and accompanied by kīrtana singers, would visit the places of Lord Kṛṣṇa’s pastimes and in the evening arrive in camp.

| | El grupo del parikrama viajó con una organización eficiente. Una avanzada llevaba toda la ropa de cama y las carpas, iría al lugar del día siguiente, donde acamparían y prepararían la cocina. Mientras tanto, el grupo principal, con la Deidad del Señor Caitanya Mahāprabhu acompañada por cantantes de kīrtana, visitaría los lugares de los pasatiempos del Señor Kṛṣṇa y por la tarde llegaría al campamento.

|  | The camp was divided into sections and arranged in a semicircle, and pilgrims were assigned to a particular section for the night. In the center were the quarters of Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta and the Deity of Lord Caitanya, and close by, the tents of the sannyāsīs. There were separate camps for ladies and men – married couples did not stay together. There was also a volunteer corps of guards who stayed up all night, patrolling the area. At night the camp, with its hundreds of tents with gaslights and campfires, resembled a small town, and local people would come to see, astonished at the arrangements. In the evening, everyone would gather to hear a discourse by Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī.

| | El campamento se dividió en secciones y se organizó en un semicírculo, los peregrinos fueron asignados a una sección particular para la noche. En el centro estaban las habitaciones de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta y la Deidad del Señor Caitanya y cerca, las carpas de los sannyāsīs. Había campamentos separados para damas y caballeros: las parejas casadas no se quedaban juntas. También había un cuerpo de guardias voluntarios que se quedaron despiertos toda la noche, patrullando el área. Por la noche el campamento, con sus cientos de carpas con luces de gas y fogatas, se parecía a un pequeño pueblo, la gente local venía a ver, asombrada por los arreglos. Por la noche, todos se reunían para escuchar un discurso de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī.

|  | The pilgrims would rise early each morning and chant Hare Kṛṣṇa together. Then, carrying the Deity of Lord Caitanya, they would set out in procession – kīrtana groups, the police band, the lead horse, the flag bearers, and all the pilgrims. They traveled to the holy places: the birthplace of Lord Kṛṣṇa, the place where Lord Kṛṣṇa slew Kaṁsa, the Ādi-keśava temple, Rādhā-kuṇḍa, Śyāma-kuṇḍa, and many others.

| | Los peregrinos se levantaban temprano cada mañana y cantaban Hare Kṛṣṇa juntos. Luego, llevando a la Deidad del Señor Caitanya, salían en procesión: grupos de kīrtana, la banda de policía, el caballo principal, los portadores de la bandera y todos los peregrinos. Viajaron a los lugares sagrados: el lugar de nacimiento del Señor Kṛṣṇa, el lugar donde el Señor Kṛṣṇa mató a Kaṁsa, el templo Ādi-keśava, Rādhā-kuṇḍa, Śyāma-kuṇḍa y muchos otros.

|  | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī’s massive pilgrimage had been rolling on with great success when he met with serious opposition. The local temple proprietors in Vṛndāvana objected to Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta’s awarding the sacred brahminical thread to devotees not born in the families of brāhmaṇas. Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta, throughout his lectures and writings, had repeatedly proven from the Vedic scriptures that one is a brāhmaṇa not by birth but by qualities. He often cited a verse from Sanātana Gosvāmī’s Hari-bhakti-vilāsa stating that just as base metal when mixed with mercury can become gold, so an ordinary man can become a brāhmaṇa if initiated by a bona fide spiritual master. He also often cited a verse from Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam in which the great sage Nārada tells King Yudhiṣṭhira that if one is born in the family of a śūdra but acts as a brāhmaṇa he has to be accepted as a brāhmaṇa, and if one is born in the family of a brāhmaṇa but acts as a śūdra he is to be considered a śūdra. Because the prime method of spiritual advancement in the Age of Kali is the chanting of the holy name of God, any person who chants Hare Kṛṣṇa should be recognized as a saintly person.

| | La peregrinación masiva de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī había estado rodando con gran éxito cuando se encontró con una seria oposición. Los propietarios del templo local en Vṛndāvana se opusieron a que Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta otorgara el cordón sagrado brahmínico a los devotos que no nacieron en las familias de los brāhmaṇas. A lo largo de sus conferencias y escritos Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta había demostrado repetidamente a través de las escrituras védicas que uno es un brāhmaṇa no por nacimiento sino por cualidades. A menudo citaba un verso del Hari-bhakti-vilāsa de Sanātana Gosvāmī que decía que así como el metal base cuando se mezcla con mercurio puede convertirse en oro, un hombre común puede convertirse en un brāhmaṇa si es iniciado por un maestro espiritual genuino. También a menudo citaba un verso del Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam en el que el gran sabio Nārada le dice al Rey Yudhiṣṭhira que si uno nace en la familia de un śūdra pero actúa como un brāhmaṇa, debe ser aceptado como un brāhmaṇa y si uno nace en la familia de un brāhmaṇa pero actúa como un śūdra, debe ser considerado un śūdra. Debido a que el método principal de avance espiritual en la era de Kali es el canto del santo nombre de Dios, cualquier persona que canta Hare Kṛṣṇa debe ser reconocida como una persona santa.

|  | When the local paṇḍitas approached Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī for discussion, they questioned his leniency in giving initiation and his awarding the brahminical thread and sannyāsa dress to persons of lower castes. Because of Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī’s scholarly, forceful presentation, the paṇḍitas seemed satisfied by the discussion, but when the parikrama party arrived at Vṛndāvana’s seven main temples, which had been erected by the immediate followers of Lord Caitanya, the party found the doors closed. Vṛndāvana shopkeepers closed their businesses, and some people even threw stones at the passing pilgrims. But the parikrama party, led by Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, continued in good spirits, despite the animosity, and on October 28 the party arrived at Kosi, the site of the treasury of Kṛṣṇa’s father, King Nanda.

| | Cuando los paṇḍitas locales se acercaron a Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī para discutir cuestionaron su indulgencia para dar iniciación y su concesión del cordón brahmínico y la vestimenta de sannyāsa a personas de castas inferiores. Debido a la presentación académica y contundente de Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, los paṇḍitas parecían satisfechos con lo hablado, pero cuando el grupo del parikrama llegó a los siete templos principales de Vṛndāvana, que habían sido erigidos por los discípulos inmediatos del Señor Caitanya, el grupo encontró las puertas cerradas. Los comerciantes de Vṛndāvana cerraron sus negocios y algunas personas incluso arrojaron piedras a los peregrinos que pasaban. Pero el grupo del parikrama, dirigida por Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, continuó de buen humor, a pesar de la animosidad y el 28 de octubre el grupo llegó a Kosi, el sitio de la tesorería del padre de Kṛṣṇa, el rey Nanda.

|  | Abhay arrived in Maṭhurā by train from Allahabad and approached Kosi by ricksha. The countryside was full of charm for Abhay; instead of factories and large buildings there were mostly forests, and aside from the main paved road on which he traveled, there were only dirt roads and soft sandy lanes. As a Vaiṣṇava, Abhay felt sensations an ordinary man wouldn’t. Now and then he sighted a peacock in the field, its exotic plumage proclaiming the glories of Vṛndāvana and Kṛṣṇa. Even a nondevotee, however, could appreciate the many varieties of birds, their interesting cries and songs filling the air. Occasionally a tree would be filled with madly chirping sparrows making their urgent twilight clamor before resting for the night. Even one unaware of the special significance of Vṛndāvana could feel a relief of mind in this simple countryside where people built fires from cow manure fuel and cooked their evening meals in the open, their fires adding rich, natural smells to the indefinable mixture which was the odor of the earth. There were many gnarled old trees and colorful stretches of flowers – bushes of bright violet camellia, trees abloom with delicate white pārijāta blossoms, and big yellow kadamba flowers, rarely seen outside Vṛndāvana.

| | Abhay llegó a Maṭhurā en tren desde Allahabad y se acercó a Kosi en ricksha. El campo estaba lleno de encanto para Abhay; en lugar de fábricas y grandes edificios, en su mayoría había bosques, aparte del camino principal pavimentado por el que viajaba, solo había caminos de tierra y senderos de arena suave. Como vaiṣṇava, Abhay sintió sensaciones que un hombre común no sentiría. De vez en cuando veía un pavo real en el campo, su exótico plumaje proclamaba las glorias de Vṛndāvana y Kṛṣṇa. Sin embargo incluso un no devoto podría apreciar las muchas variedades de aves, sus interesantes cantos y canciones llenando el aire. De vez en cuando un árbol se llenaba de gorriones chirriantes que hacían su urgente clamor crepuscular antes de descansar por la noche. Incluso alguien que desconoce el significado especial de Vṛndāvana podría sentir un alivio mental en este campo sencillo donde la gente encendía fuegos de estiércol de vaca y cocinaba sus cenas al aire libre, sus fuegos agregaban olores naturales y ricos a la mezcla indefinible que era el olor de la tierra. Había muchos árboles viejos nudosos y flores coloridas: arbustos de camelia violeta brillante, árboles en flor con delicadas flores blancas de pārijāta y grandes flores amarillas de kadamba, raramente vistas fuera de Vṛndāvana.

|  | On the road there was lively horse-drawn ṭāṅgā traffic. The month of Kārttika, October-November, was one of the several times of the year that drew many pilgrims to Vṛndāvana. The one-horse ṭāṅgās carried large families, some coming from hundreds of miles away. Larger bands of pilgrims, grouped by village, walked together, the women dressed in bright-colored sārīs, brown-skinned men and women sometimes singing bhajanas, carrying but a few simple possessions as they headed for the town of thousands of temples, Vṛndāvana. And there were businessmen like Abhay, dressed more formally, coming from a city, maybe to spend the weekend. Most of them had at least some semblance of a religious motive – to see Kṛṣṇa in the temple, to bathe in the holy Yamunā River, to visit the sites where Lord Kṛṣṇa had performed His pastimes such as the lifting of Govardhana Hill, the killing of the Keśī demon, or the dancing in the evening with the gopīs.

| | En el camino había un intenso tráfico de ṭāṅgās tiradas por caballos. El mes de Kārttika, octubre-noviembre, fue una de las varias veces del año que atrajo a muchos peregrinos a Vṛndāvana. Las ṭāṅgās de un caballo llevaban familias numerosas, algunas de ellas a cientos de kilómetros de distancia. Grandes grupos de peregrinos, agrupados por pueblo, caminaron juntos, las mujeres vestidas con sārīs de colores brillantes, hombres y mujeres de piel marrón que a veces cantaban bhajanas, llevando solo algunas sencillas posesiones mientras se dirigían a la ciudad de miles de templos, Vṛndāvana. Y había hombres de negocios como Abhay, vestidos más formalmente, procedentes de una ciudad, tal vez para pasar el fin de semana. La mayoría de ellos tenían al menos una especie de motivo religioso: ver a Kṛṣṇa en el templo, bañarse en el río sagrado de Yamunā, visitar los lugares donde el Señor Kṛṣṇa había realizado sus pasatiempos, como el levantamiento de la colina Govardhana, el asesinato de el demonio Keśī, o el baile nocturno con las gopīs.

|  | Abhay was sensitive to the atmosphere of Vṛndāvana, and he noted the activity along the road. But more than that, he cherished with anticipation the fulfillment of his journey – his meeting again, after a long separation, the saintly person he had always thought of within himself, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, who had spoken to him in Calcutta and had convinced him of Lord Caitanya’s mission to preach Kṛṣṇa consciousness. Abhay would soon see him again, and this purpose filled his mind.

| | Abhay era sensible a la atmósfera de Vṛndāvana, notó la actividad a lo largo del camino. Pero más que eso, apreciaba con anticipación el cumplimiento de su viaje: su encuentro nuevamente, después de una larga separación, con la persona santa en la que siempre había pensado, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, que le había hablado en Calcuta y lo había convencido de la misión del Señor Caitanya, de predicar la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa. Abhay pronto lo volvería a ver, este propósito llenó su mente.

|  | Upon reaching the lantern-illuminated camp of the Gauḍīya Maṭh and inquiring at the registration post, he was allowed to join the parikrama village. He was assigned to a tent of gṛhastha men and was offered prasādam. The people were friendly and in good spirits, and Abhay talked of his activities with the maṭha members in Calcutta and Allahabad. Then there was a gathering – a sannyāsī was making an announcement. This evening, he said, there would be a scheduled visit to a nearby temple to see the Deity of Śeṣaśāyī Viṣṇu. Some of the pilgrims cheered, “Haribol! Hare Kṛṣṇa!” The sannyāsī also announced that His Divine Grace Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura would speak that evening for the last time and would be leaving the parikrama party the next day. So there was a choice of going on the parikrama or staying for the lecture.

| | Al llegar al campamento del Maṭh Gauḍīya, iluminado con faroles e indagar en el puesto de registro, se le permitió unirse a la aldea del parikrama. Fue asignado a una carpa de hombres gṛhasthas y se le ofreció prasādam. La gente era amigable y estaba de buen humor, Abhay habló de sus actividades con los miembros del maṭh en Calcuta y Allahabad. Luego hubo una reunión: un sannyāsī estaba haciendo un anuncio. Esta noche habría una visita programada a un templo cercano para ver a la Deidad de Śeṣaśāyī Viṣṇu. Algunos de los peregrinos vitorearon: “¡Haribol! ¡Hare Kṛṣṇa!” El sannyāsī también anunció que Su Divina Gracia Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura hablaría esa tarde por última vez y se iría del grupo de parikrama al día siguiente. Así que había la opción de ir al parikrama o quedarse para la conferencia.

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda: So I met them in Kosi, and Keśava Mahārāja was informing that Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta is going to Maṭhurā tomorrow morning and he will speak hari-kathā this evening. Anyone who wants to may remain. Or otherwise they may go to see Śeṣaśāyī Viṣṇu. So at that time I think only ten or twelve men remained – Śrīdhara Mahārāja was one of them. And I thought it wise, “What can I see at this Śeṣaśāyī? Let me hear what Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī will speak. Let me hear.”

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda: Entonces los encontré en Kosi, Keśava Mahārāja estaba informando que Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta irá a Maṭhurā mañana por la mañana y hablará hari-kathā esta tarde. Cualquiera que quiera puede permanecer. O de lo contrario, pueden ir a ver a Śeṣaśāyī Viṣṇu. Entonces, en ese momento creo que solo quedaban diez o doce hombres: Śrīdhara Mahārāja era uno de ellos. Y pensé que tenía razón: “¿Qué puedo ver en este Śeṣaśāyī? Déjame escuchar lo que Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī hablará. Dejame escuchar".

|  | When Abhay arrived, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta was already speaking. He sat with his back erect, a shawl around his shoulders, not speaking like a professional lecturer giving a scheduled performance, but addressing a small gathering in his room. At last Abhay was in his presence again. Abhay marveled to see and hear him, this unique soul possessed of kṛṣṇa-kathā, speaking uninterruptedly about Kṛṣṇa in his deep, low voice, in ecstasy and deep knowledge. Abhay sat and heard with rapt attention.

| | Cuando llegó Abhay, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta ya estaba hablando. Se sentó con la espalda erguida, con un chal sobre los hombros, no hablaba como un profesor profesional dando una actuación programada, sino dirigiéndose a una pequeña reunión en su habitación. Por fin Abhay volvió a estar en su presencia. Abhay se maravilló al verlo y escucharlo, esta alma única obsesionada por al kṛṣṇa-kathā, que habla ininterrumpidamente sobre Kṛṣṇa con su voz grave y profunda, en éxtasis y conocimiento profundo. Abhay se sentó y escuchó con gran atención.

|  | Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī had been speaking regularly about sambandha, abhidheya, and prayojana. Sambandha is the stage of devotional service in which awareness of God is awakened, abhidheya is rendering loving service to the Lord, and prayojana is the ultimate goal, pure love of God. He stressed that his explanations were in exact recapitulation of what had originally been spoken by Kṛṣṇa and passed down through disciplic succession. Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī’s particular utterance, mostly Bengali but sometimes English, with frequent quoting of Sanskrit from the śāstras, was deep with erudition. “It is Kṛṣṇa,” said Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, “who is the only Superlord over the entire universe and, beyond it, of Vaikuṇṭha, the transcendental region. As such, no one can raise any obstacle against His enjoyment.”

| | Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī había estado hablando regularmente sobre sambandha, abhidheya y prayojana. Sambandha es la etapa del servicio devocional en la que se despierta la conciencia de Dios, abhidheya está prestando un servicio amoroso al Señor y prayojana es la meta final, el amor puro de Dios. Hizo hincapié en que sus explicaciones eran una recapitulación exacta de lo que Kṛṣṇa había dicho originalmente y transmitido a través de la sucesión discipular. Las palabras de Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, principalmente en bengalí pero a veces en inglés, con citas frecuentes del sánscrito de los śāstras, fueron profundas y con erudición. “Es Kṛṣṇa”, dijo Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, “quien es el único Superser sobre todo el universo y más allá, de Vaikuṇṭha, la región trascendental. Como tal, nadie puede levantar ningún obstáculo contra su gozo".

|  | An hour went by, two hours … . The already small gathering in Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta’s room gradually thinned. A few sannyāsīs left, excusing themselves to tend to duties connected with the parikrama camp. Only a few intimate leaders remained. Abhay was the only outsider. Of course, he was a devotee, not an outsider, but in the sense that he was not a sannyāsī, was not handling any duties, was not even initiated, and was not traveling with the parikrama but had joined only for a day – in that sense he was an outsider. The philosophy Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī was speaking, however, was democratically open to whoever would give an ardent hearing. And that Abhay was doing.

| | Pasó una hora, dos horas ... La ya pequeña reunión en la habitación de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta se fue disminuyendo gradualmente. Unos pocos sannyāsīs se fueron, excusándose para atender tareas relacionadas con el campamento de parikrama. Solo quedaban unos pocos líderes íntimos. Abhay era el único extraño. Por supuesto, él era un devoto, no un extraño, pero en el sentido de que no era un sannyāsī, no estaba cumpliendo ningún deber, ni siquiera estaba iniciado y no viajaba con el parikrama, sino que se había unido solo por un día, esa sensación de que era un extraño. Sin embargo la filosofía que Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī estaba hablando era democráticamente abierta a quien quisiera escuchar fervorosamente. Y eso es lo que Abhay estaba haciendo.

|  | He was listening with wonder. Sometimes he would not even understand something, but he would go on listening intently, submissively, his intelligence drinking in the words. He felt Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī revealing to him the direct vision of the spiritual world, just as a person reveals something by opening a door or pushing aside a curtain. He was revealing the reality, and this reality was loving service to the lotus feet of Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa, the supremely worshipable Personality of Godhead. How masterfully he spoke! And with utter conviction and boldness!

| | Estaba escuchando con asombro. A veces ni siquiera entendía cosas, pero seguía escuchando atentamente, sumisamente, su inteligencia absorbiendo las palabras. Sintió que Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī le reveló la visión directa del mundo espiritual, así como una persona revela algo abriendo una puerta o apartando una cortina. Él estaba revelando la realidad, esta realidad era un servicio amoroso a los pies de loto de Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa, la Suprema y Adorable Personalidad de Dios. ¡Cuán magistralmente habló! ¡Y con absoluta convicción y fuerza!

|  | It was with such awe that Abhay listened with fastened attention. Of course, all Vaiṣṇavas accepted Kṛṣṇa as their worshipable Lord, but how conclusively and with what sound logic was the faith of the Vaiṣṇavas established by this great teacher! After several hours, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī stopped speaking. Abhay felt prepared to go on listening without cessation, and yet he had no puzzling doubts or queries to place forward. He wanted only to hear more. As Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta made his exit, Abhay bowed, offering his obeisances, and then left the intimate circle of sannyāsīs in their row of tents and went to the outer circle of tents, his mind surcharged with the words of his spiritual master.

| | Con tanto asombro, Abhay escuchó con atención fija. Por supuesto que todos los vaiṣṇavas aceptan a Kṛṣṇa como su adorable Señor, pero ¡cuán concluyente y con qué lógica tan sólida es la fe de los vaiṣṇavas establecida por este gran maestro! Después de varias horas, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī dejó de hablar. Abhay se sintió preparado para seguir escuchando sin cesar y sin embargo, no tenía dudas ni preguntas desconcertantes que plantear. Solo quería escuchar más. Cuando Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta hizo su salida, Abhay se inclinó, ofreciéndole reverencias y dejó el círculo íntimo de sannyāsīs en su fila de carpas y se fue al círculo exterior de tiendas de campaña, su mente cargada con las palabras de su maestro espiritual.

|  | Now their relationship seemed more tangible. He still treasured his original impression of Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, the saintly person who had spoken to him on the rooftop in Calcutta; but tonight that single impression that had sustained him for years in Allahabad had been enriched and filled with new life. His spiritual master and the impression of his words were as much a reality as the stars in the sky and the moon over Vṛndāvana. That impression of hearing from Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī was filling him with its reality, and all other reality was forming itself around the absolute reality of Śrīla Gurudeva, just as all the planets circle around the sun.

| | Ahora su relación parecía más tangible. Todavía atesoraba su impresión original sobre Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, la persona santa que le había hablado en la azotea de Calcuta; pero esta noche esa única impresión que lo había sostenido durante años en Allahabad se había enriquecido y llenado de nueva vida. Su maestro espiritual y la impresión de sus palabras eran tan reales como las estrellas en el cielo y la luna sobre Vṛndāvana. Esa impresión de escuchar de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī lo estaba llenando de su realidad y otra realidad se estaba formando alrededor de la realidad absoluta de Śrīla Gurudeva, tal como todos los planetas giran alrededor del sol.

|  | The next morning, Abhay was up with the others more than an hour before dawn, bathed, and chanting mantras in congregation. Later in the morning the tall, stately figure of Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, dressed in plain saffron, got into the back seat of a car and rode away from the camp. Thoughtful and grave, he looked back and waved, accepting the loving farewell gestures of his followers. Abhay stood amongst them.

| | A la mañana siguiente, Abhay se levantó con los demás una hora antes del amanecer, se bañó y recitó mantras en la congregación. Más tarde en la mañana, la figura alta y majestuosa de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, vestido sencillo de azafrán, se subió al asiento trasero de un automóvil y se alejó del campamento. Pensativo y serio, miró hacia atrás y saludó, aceptando los gestos de despedida amorosa de sus seguidores. Abhay se paró entre ellos.

|  | A little more than a month later, Abhay was again anticipating an imminent meeting with Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta, this time at Allahabad. Abhay had only recently returned from Vṛndāvana to his work at Prayag Pharmacy when the devotees at the Allahabad Gauḍīya Maṭh informed him of the good news. They had secured land and funds for constructing a building, the Śrī Rūpa Gauḍīya Maṭh, and Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta would be coming on November 21 to preside over the ceremony for the laying of the cornerstone. Sir William Malcolm Haily, governor of the United Provinces, would be the respected guest and, in a grand ceremony, would lay the foundation stone in the presence of Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta. When Abhay learned that there would also be an initiation ceremony, he asked if he could be initiated. Atulānanda, the maṭha’s president, assured Abhay that he would introduce him to Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī.

| | Poco más de un mes después, Abhay nuevamente anticipaba una reunión inminente con Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta, esta vez en Allahabad. Abhay había regresado recientemente de Vṛndāvana a su trabajo en la Farmacia Prayag cuando los devotos del Maṭh Gauḍīya de Allahabad le informaron de las buenas noticias. Habían asegurado tierras y fondos para construir un edificio, Śrī Rūpa Gauḍīya Maṭh y Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta vendrían el 21 de noviembre para presidir la ceremonia de colocación de la primera piedra. Sir William Malcolm Haily, gobernador de las Provincias Unidas, sería el invitado prominente y en una gran ceremonia pondría la primera piedra en presencia de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta. Cuando Abhay se enteró de que también habría una ceremonia de iniciación, preguntó si podía ser iniciado. Atulānanda, el presidente del maṭha, le aseguró a Abhay que lo presentaría a Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī.

|  | At home, Abhay discussed his initiation plans with his wife. She had no objection, but she did not want to take initiation herself. They were already worshiping the Deity at home and offering their food to the Deity. They believed in God and were living peacefully.

| | En casa, Abhay comentó sus planes de iniciación con su esposa. Ella no tenía objeciones, pero no quería iniciarse ella misma. Ya estaban adorando a la Deidad en casa y ofreciendo su comida a la Deidad. Creía en Dios y vivían en paz.

|  | But for Abhay that was not enough. Although he would not force his wife, he knew that he must be initiated by a pure devotee. Avoiding sinful life, living piously – these things were necessary and good, but in themselves they did not constitute spiritual life and could not satisfy the yearning of the soul. Life’s ultimate goal and the absolute necessity of the self was love of Kṛṣṇa. That love of Kṛṣṇa his father had already inculcated within him, and now he had to take the next step. His father would have been pleased to see him do it.

| | Pero para Abhay eso no era suficiente. Aunque no forzaría a su esposa, sabía que debía ser iniciado por un devoto puro. Evitar la vida pecaminosa, vivir piadosamente: estas cosas eran necesarias y buenas, pero en sí mismas no constituían vida espiritual y no podían satisfacer el anhelo del alma. El objetivo final de la vida y la necesidad absoluta de uno mismo era el amor por Kṛṣṇa. Ese amor por Kṛṣṇa que su padre ya había inculcado dentro de él, ahora tenía que dar el siguiente paso. A su padre le hubiera encantado verlo hacerlo.

|  | What he had learned from his father was now being solidified by someone capable of guiding all the fallen souls of the world to transcendental love of God. Abhay knew he should go forward and take complete shelter in the instructions of his spiritual master. And the scriptures enjoined, “He who is desirous of knowing the Absolute Truth must take shelter of a spiritual master who is in disciplic succession and who is fixed in Kṛṣṇa consciousness.” Even Lord Caitanya, who was Kṛṣṇa Himself, had accepted a spiritual master, and only after initiation did He manifest the full symptoms of ecstatic love of Kṛṣṇa while chanting the holy name.

| | Lo que había aprendido de su padre ahora estaba siendo solidificado por alguien capaz de guiar a todas las almas caídas del mundo hacia el amor trascendental por Dios. Abhay sabía que debía avanzar y refugiarse por completo en las instrucciones de su maestro espiritual. Las Escrituras ordenaban: “El que desee conocer la Verdad Absoluta debe refugiarse en un maestro espiritual que está en sucesión discipular y que está fijo en la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa". Incluso el Señor Caitanya, quien era Kṛṣṇa mismo, había aceptado a un maestro espiritual y solo después de la iniciación manifestó todos los síntomas del amor extático por Kṛṣṇa mientras cantaba el santo nombre.

|  | As for the ritual initiation he had received at age twelve from a family priest, Abhay had never taken it very seriously. It had been a religious formality. But a guru was not a mere officiating ritualistic priest; so Abhay had rejected the idea that he already had a guru. He had never received instructions from him in bhakti, and his family guru had not linked him, through disciplic succession, with Kṛṣṇa. But by taking initiation from Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī he would be linked with Kṛṣṇa. Bhaktisiddhānta, son of Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura and disciple of Gaurakiśora dāsa Bābājī, was the guru in the twelfth disciplic generation from Lord Caitanya. He was the foremost Vedic scholar of the age, the expert Vaiṣṇava who could guide one back to Godhead. He was empowered by his predecessors to work for the highest welfare by giving everyone Kṛṣṇa consciousness, the remedy for all sufferings. Abhay felt that he had already accepted Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta as his spiritual master and that from their very first meeting he had already received his orders. Now if Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta would accept him as his disciple, the relationship would be confirmed.

| | En cuanto a la iniciación ritual que había recibido a los doce años de un sacerdote familiar, Abhay nunca lo había tomado muy en serio. Había sido una formalidad religiosa. Pero un guru no era un simple sacerdote ritualista oficiante; así que Abhay había rechazado la idea de que él ya tuviera un guru. Nunca había recibido instrucciones de él en bhakti y su guru familiar no lo había vinculado con Kṛṣṇa a través de la sucesión discipular. Pero al tomar la iniciación de Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, él estaría finalmente vinculado con Kṛṣṇa. Bhaktisiddhānta, hijo de Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura y discípulo de Gaurakiśora dāsa Bābājī, fue el guru en la duodécima generación discipular del Señor Caitanya. Era el erudito védico más importante de la época, un vaiṣṇava experto que podía guiar a uno de regreso a Dios. Sus predecesores le dieron el poder para trabajar por el mayor bienestar al darles a todos la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa, el remedio para todos los sufrimientos. Abhay sintió que ya había aceptado a Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta como su maestro espiritual y que desde su primer encuentro ya había recibido sus instruciones. Ahora si Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta lo aceptaba como su discípulo, la relación se confirmaría.

|  | He was coming so soon after Abhay had seen and heard him in Vṛndāvana! That was how Kṛṣṇa acted, through His representative. It was as if his spiritual master, in coming to where Abhay had his family and business, was coming to draw him further into spiritual life. Without Abhay’s having attempted to bring it about, his relationship with Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta was deepening. Now Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta was coming to him, as if by a higher arrangement.

| | ¡Era tan pronto después de que Abhay lo había visto y oído en Vṛndāvana! Así fue como Kṛṣṇa actuó, a través de Su representante. Era como si su maestro espiritual al llegar a donde Abhay tenía su familia y negocios, iba a atraerlo más a la vida espiritual. Sin que Abhay hubiera intentado hacerlo, su relación con Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta se estaba profundizando. Ahora Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta se acercaba a él, como por un arreglo superior.

|  | On the day of the ceremony, Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī met with his disciples at the Allahabad Gauḍīya Maṭh on South Mallaca Street. While he was speaking hari-kathā and taking questions, Atulānanda Brahmacārī took the opportunity to present several devotees, Abhay amongst them, as candidates for initiation. The Allahabad devotees were proud of Mr. De, who regularly attended the maṭha in the evening, and led bhajanas, listened to the teachings and spoke them himself, and often brought respectable guests. He had contributed money and had induced his business colleagues also to do so. With folded palms, Abhay looked up humbly at his spiritual master. He and Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta were now face to face, and Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta recognized him and was visibly pleased to see him. He already knew him. “Yes,” he said, exchanging looks with Abhay, “he likes to hear. He does not go away. I have marked him. I will accept him as my disciple.”

| | El día de la ceremonia, Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī se reunió con sus discípulos en la Gauḍīya Maṭh de Allahabad en la calle South Mallaca. Mientras hablaba hari-kathā y respondía preguntas, Atulānanda Brahmacārī aprovechó la oportunidad para presentar a varios devotos, Abhay entre ellos, como candidatos para la iniciación. Los devotos de Allahabad estaban orgullosos del Sr. De, que asistía regularmente al maṭh por la noche y dirigía bhajanas, escuchaba las enseñanzas y las hablaba él mismo y a menudo traía invitados respetables. Había aportado dinero y había inducido a sus colegas de negocios a hacerlo también. Con las palmas juntas, Abhay miró humildemente a su maestro espiritual. Él y Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta ahora estaban cara a cara, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta lo reconoció y se sintió visiblemente complacido de verlo. Él ya lo conocía. “Sí", dijo, intercambiando miradas con Abhay, “le gusta escuchar. Él no se va. Ya lo noté, lo aceptaré como mi discípulo.

|  | As the moment and the words became impressed into his being, Abhay was in ecstasy. Atulānanda was pleasantly surprised that his Gurudeva was already in approval of Mr. De. Other disciples in the room were also pleased to witness Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī’s immediate acceptance of Mr. De as a good listener. Some of them wondered when or where Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta had arrived at such an estimation of the young pharmacist.

| | Cuando el momento y las palabras quedaron impresas en su ser, Abhay estaba en éxtasis. Atulānanda se sorprendió gratamente de que su Gurudeva aprobara al Sr. De. Otros discípulos en la sala también se complacieron de presenciar la aceptación inmediata por Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī del Sr. De como un buen oyente. Algunos de ellos se preguntaban cuándo o dónde Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta había llegado a tal estimación del joven farmacéutico.

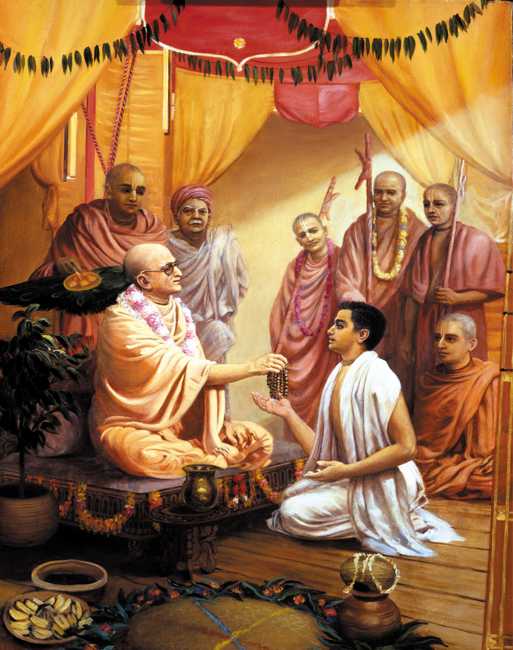

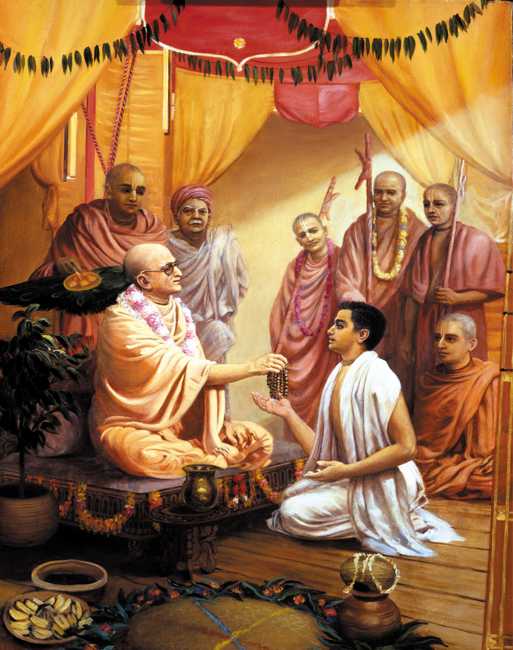

|  | At the initiation, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī was seated on a vyāsāsana, and the room was filled with guests and members of the Gauḍīya Maṭh. Those to be initiated sat around a small mound of earth, where one of Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī’s sannyāsīs prepared a fire and offered grains and fruits into the flames, while everyone chanted mantras for purification. Abhay’s sister and brother were present, but not his wife.

| | En la iniciación, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī estaba sentado en un vyāsāsana, la sala estaba llena de invitados y miembros del Maṭh Gauḍīya. Los iniciados se sentaron alrededor de un pequeño montículo de tierra, donde uno de los sannyāsīs de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī preparó un fuego y ofreció granos y frutas a las llamas, mientras todos cantaban mantras para la purificación. La hermana y el hermano de Abhay estaban presentes, pero no su esposa.

|  | Abhay basked in the presence of his Gurudeva. “Yes, he likes to hear” – the words of his spiritual master and his glance of recognition had remained with Abhay. Abhay would continue pleasing his spiritual master by hearing well. “Then,” he thought, “I will be able to speak well.” The Vedic literature described nine processes of devotional service, the first of which was śravaṇam, hearing about Kṛṣṇa; then came kīrtanam, chanting about and glorifying Him. By sitting patiently and hearing at Kosi, he had pleased Kṛṣṇa’s representative, and when Kṛṣṇa’s representative was pleased, Kṛṣṇa was pleased. Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī had not praised him for donating money to the maṭha and hadn’t advised him to forsake his family and business and travel with him, nor had he asked Abhay to perform great austerities, like the yogīs who mortify their bodies with fasts and difficult vows. But “He likes to hear,” he had said. “I have marked him.” Abhay thought about it and, again, listened carefully as his spiritual master conducted the initiation.

| | Abhay se regodeó en presencia de su Gurudeva. “Sí, le gusta escuchar": las palabras de su maestro espiritual y su mirada de reconocimiento habían permanecido con Abhay. Abhay continuaría complaciendo a su maestro espiritual al escuchar bien. “Entonces", pensó,. “podré hablar bien". La literatura védica describe los nueve procesos del servicio devocional, el primero de los cuales es śravaṇam escuchar de Kṛṣṇa; Luego viene kīrtanam, cantar y glorificarlo. Al sentarse pacientemente y escuchar en Kosi, había complacido al representante de Kṛṣṇa y cuando el representante de Kṛṣṇa estaba complacido, Kṛṣṇa estaba complacido. Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī no lo había elogiado por donar dinero al maṭh ni le había aconsejado que abandonara a su familia y sus negocios y viajara con él, ni le había pedido a Abhay que realizara grandes austeridades, como los yogīs que mortifican sus cuerpos con ayunos y votos difíciles. Pero “le gusta escuchar,” había dicho. “Lo he notado". Abhay lo pensó y nuevamente, escuchó atentamente mientras su maestro espiritual conducía la iniciación.

|  | Finally, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta called for Abhay to come forward and receive the hari-nāma initiation by accepting his beads. After offering prostrated obeisances, Abhay extended his right hand and accepted the strand of japa beads from the hand of his spiritual master. At the same time, he also received the sacred brahminical thread, signifying second initiation. Usually, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta gave the first initiation, harināma, and only after some time, when he was satisfied with the progress of the disciple, would he give the second initiation. But he offered Abhay both initiations at the same time. Now Abhay was a full-fledged disciple, a brāhmaṇa, who could perform sacrifices, such as this fire yajña for initiation; he could worship the Deity in the temple and would be expected to discourse widely. Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta added aravinda, “lotus,” to his name; now he was Abhay Charanaravinda.

| | Finalmente, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta llamó a Abhay a presentarse, recibir la iniciación hari-nāma y aceptar sus cuentas. Después de ofrecer reverencias postradas, Abhay extendió su mano derecha y aceptó el rosario de cuentas de japa de la mano de su maestro espiritual. Al mismo tiempo, también recibió el cordón sagrado brahmínico, lo que significa una segunda iniciación. Usualmente, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta daba la primera iniciación harināma y solo después de algún tiempo, cuando estaba satisfecho con el progreso del discípulo, daría la segunda iniciación. Pero le ofreció a Abhay ambas iniciaciones al mismo tiempo. Ahora Abhay era un discípulo de pleno derecho, un brāhmaṇa, que podía realizar sacrificios, como este fuego yajña para la iniciación; él podría adorar a la Deidad en el templo y se esperaría que predicara ampliamente. Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta agregó aravinda, “loto", a su nombre; ahora era Abhay Charanaravinda.

|  | After Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī left Allahabad for Calcutta, Abhay keenly felt the responsibility of working on behalf of his spiritual master. At the initiation Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta had instructed Abhay to study Rūpa Gosvāmī’s Bhakti-rasāmṛta-sindhu, which outlined the loving exchanges between Kṛṣṇa and His devotees and explained how a devotee can advance in spiritual life. Bhakti-rasāmṛta-sindhu was a “lawbook” for devotional service, and Abhay would study it carefully. He was glad to increase his visits to the Allahabad center and to bring new people. Even at his first meeting with his spiritual master he had received the instruction to preach the mission of Lord Caitanya, and now he began steadily and carefully considering how to do so. Preaching was a responsibility at least as binding as that of home and business. Even in his home he wanted to engage as far as possible in preaching. He discussed with his wife about his plans for inviting people into their home, offering them prasādam, and holding discussions about Kṛṣṇa. She didn’t share his enthusiasm.

| | Después de que Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī dejó Allahabad hacia Calcuta, Abhay sintió profundamente la responsabilidad de trabajar en nombre de su maestro espiritual. En la iniciación, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta le había ordenado a Abhay que estudiara el Bhakti-rasāmṛta-sindhu de Rūpa Gosvāmī, que describía los intercambios amorosos entre Kṛṣṇa y Sus devotos y explicaba cómo un devoto puede avanzar en la vida espiritual. Bhakti-rasāmṛta-sindhu era un “libro de leyes” para el servicio devocional, Abhay lo estudiaría cuidadosamente. Se alegró de aumentar sus visitas al centro de Allahabad y de traer nuevas personas. Incluso en su primer encuentro con su maestro espiritual, había recibido la instrucción de predicar la misión del Señor Caitanya, ahora comenzó a considerar de manera constante y cuidadosa cómo hacerlo. La predica era una responsabilidad al menos tan vinculante como la del hogar y el negocio. Incluso en su casa quería participar lo más posible en la predica. Habló con su esposa sobre sus planes para invitar a las personas a su hogar, ofrecerles prasādam y mantener conversaciones sobre Kṛṣṇa. Ella no compartió su entusiasmo.

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda: My wife was a devotee of Kṛṣṇa, but she had some other idea. Her idea was just to worship the Deity at home and live peacefully. My idea was preaching.

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda: Mi esposa era devota de Kṛṣṇa, pero tenía otra idea. Su idea era simplemente adorar a la Deidad en casa y vivir en paz. Mi idea era predicar.

|  | It was not possible for Abhay to travel with his spiritual master or even to see him often. His pharmaceutical business kept him busy, and he traveled frequently. Whenever possible, however, he tried to time a business trip to Calcutta when his spiritual master was also there. Thus over the next four years he managed to see his spiritual master perhaps a dozen times.

| | Abhay no podía viajar con su maestro espiritual ni verlo a menudo. Su negocio farmacéutico lo mantuvo ocupado y viajaba con frecuencia. Sin embargo, siempre que le fue posible, trató de programar un viaje de negocios a Calcuta cuando su maestro espiritual también estaba allí. Así, durante los siguientes cuatro años, logró ver a su maestro espiritual tal vez una docena de veces.

|  | Whenever Abhay visited Calcutta, the assistant librarian at the Gauḍīya Maṭh, Nityānanda Brahmacārī, would meet him at Howrah train station with a two-horse carriage belonging to the maṭha. Nityānanda saw Abhay as an unusually humble and tolerant person. As they rode together to the maṭha, Abhay would inquire eagerly into the latest activities of Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta: his traveling, his publishing, how many centers were currently open, how his disciples were doing. They wouldn’t talk much about Abhay’s business. Abhay would stay at the Gauḍīya Maṭh, usually for about five days. Sometimes he would visit one of his sisters who lived in Calcutta, but his main reason for coming was Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta; and Abhay would take advantage of every opportunity to hear him.

| | Cada vez que Abhay visitaba Calcuta, el bibliotecario asistente del Maṭh Gauḍīya, Nityānanda Brahmacārī, lo encontraba en la estación de tren de Howrah con un carruaje de dos caballos perteneciente al maṭh. Nityānanda vio a Abhay como una persona inusualmente humilde y tolerante. Mientras cabalgaban juntos hacia el maṭh, Abhay indagaría ansiosamente sobre las últimas actividades de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta: sus viajes, su publicación, cuántos centros estaban abiertos actualmente, cómo estaban sus discípulos. No hablarían mucho sobre los negocios de Abhay. Abhay se quedaba en la Gauḍīya Maṭh, generalmente durante unos cinco días. Algunas veces visitaba a una de sus hermanas que vivía en Calcuta, pero su razón principal para venir era Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta; y Abhay aprovecharía cada oportunidad para escucharlo.

|  | Abhay didn’t try to become a leader in the inner management of the Gauḍīya Maṭh. His spiritual master had initiated eighteen sannyāsīs, who carried out most of the preaching and leadership of the mission. Abhay was always the householder, occupied with his own business and family, never living within the maṭha except for brief visits. And yet he began to develop a close relationship with his spiritual master.

| | Abhay no trató de convertirse en un líder en la gestión interna del Maṭh Gauḍīya. Su maestro espiritual había iniciado dieciocho sannyāsīs, quienes llevaron a cabo la mayor parte de la predica y el liderazgo de la misión. Abhay siempre fue el jefe de familia, ocupado con su propio negocio y familia, nunca viviendo dentro del maṭh, excepto por breves visitas. Sin embargo, comenzó a desarrollar una relación cercana con su maestro espiritual.

|  | Sometimes Abhay would go to see him at the Caitanya Maṭh, at the birthplace of Lord Caitanya in Māyāpur. One day at the Caitanya Maṭh, Abhay was in the courtyard when a large poisonous snake crawled out in front of him. Abhay called out for his Godbrothers, but when they came everyone simply stood looking, uncertain what to do. Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta came out on the veranda of the second floor, glanced down, saw the snake, and immediately ordered, “Kill it.” A boy then took a large stick and killed the snake.

| | A veces, Abhay iba a verlo al Caitanya Maṭh, en el lugar de nacimiento del Señor Caitanya en Māyāpur. Un día en el Caitanya Maṭh, Abhay estaba en el patio cuando una gran serpiente venenosa se arrastró frente a él. Abhay llamó a sus hermanos espirituales, pero cuando vinieron todos simplemente se quedaron mirando, sin saber qué hacer. Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta salió a la terraza del segundo piso, miró hacia abajo, vio la serpiente e inmediatamente ordenó: “Mátala". Un joven tomó un palo grande y mató a la serpiente.

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda: So I thought, “How is it that Guru Mahārāja ordered the snake to be killed?” I was a little surprised, but later on I saw this verse, and then I was very glad: modeta sādhur api vṛścika-sarpa-hatyā, “Even saintly persons take pleasure in the killing of a scorpion or a snake.” It had remained a doubt, how Guru Mahārāja ordered the snake to be killed, but when I read this verse I was very much pleased that this creature or creatures like the snake should not be shown any mercy.

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda: Entonces pensé: “¿Cómo es que Guru Mahārāja ordenó que mataran a la serpiente?.” Me sorprendió un poco, pero más tarde vi este verso y me alegré mucho: modeta sādhur api vṛścika-sarpa-hatyā,. “Incluso las personas santas se complacen cuando matan a un escorpión o una serpiente". Le permaneció la duda de cómo Guru Mahārāja ordenó que mataran a la serpiente, pero cuando leí este verso, me complació mucho que a esta creatura o creaturas no se le mostrara ninguna misericordia.

|  | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta was reputed to be so austere and so strong in argument against other philosophies that even his own disciples were cautious in approaching him if he were sitting alone or if they had no specific business with him. Yet even though Abhay’s contact with him was quite limited, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta would always treat him kindly.

| | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta tenía fama de ser tan austero y tan fuerte en el argumento contra otras filosofías que incluso sus propios discípulos fueron cautelosos al acercarse a él si estaba sentado solo o si no tenían asuntos específicos con él. Sin embargo, aunque el contacto de Abhay con él era bastante limitado, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta siempre lo trataría con amabilidad.

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda: Whenever I met my Guru Mahārāja, he would always treat me very affectionately. Sometimes my Godbrothers would criticize because I would talk a little freely with him, and they would quote this English saying, “Fools rush in where angels fear to tread.” But I would think, “Fool? Well, maybe, but that is the way I am.” My Guru Mahārāja was always very, very affectionate to me. When I offered obeisances, he used to return, “Dāso ’smi”: “I am your servant.”

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda: Cada vez que me encontraba con mi Guru Mahārāja me trataba con mucho cariño. A veces, mis hermanos espirituales criticaban porque hablaba tan libremente con él y citaban este dicho en inglés: “Los tontos se apresuran donde los ángeles temen pisar". Pero yo pensaría: “¿Tonto? Bueno, tal vez, pero así soy yo. Mi Guru Mahārāja siempre fue muy, muy cariñoso conmigo. Cuando le ofrecía reverencias, él solía contestar, “Dāso’ smi “: ”Soy tu sirviente".

|  | Sometimes as Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta paced back and forth chanting the Hare Kṛṣṇa mantra aloud while fingering his beads, Abhay would enter the room and also chant, walking alongside his spiritual master. Once when Abhay entered Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta’s room, his spiritual master was sitting on a couch, and Abhay took his seat beside him on an equal level. But then he noticed that all the other disciples in the room were sitting on a lower level, at their spiritual master’s feet. Abhay kept his seat, and Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī said nothing of it, but Abhay never again sat on an equal level with his spiritual master.

| | A veces, mientras Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta caminaba de un lado a otro rezando el mantra Hare Kṛṣṇa en voz alta mientras tocaba sus cuentas, Abhay entraba en la habitación y también rezaba, caminando junto a su maestro espiritual. Una vez, cuando Abhay entró en la habitación de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta, su maestro espiritual estaba sentado en un sofá, Abhay se sentó a su lado al mismo nivel. Pero luego notó que todos los otros discípulos en la sala estaban sentados en un nivel inferior, a los pies de su maestro espiritual. Abhay mantuvo su asiento y Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī no dijo nada al respecto, pero Abhay nunca más se sentó al mismo nivel que su maestro espiritual.

|  | Once in a room with many disciples, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī was speaking and Abhay listening when an old man beside Abhay motioned to him. As Abhay leaned over to hear what the man wanted, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta suddenly spoke out in annoyance at the two apparently inattentive students. “Bābū,” he first addressed the old man beside Abhay, “do you think you have purchased me with your 150-rupees-per-month donation?” And then, turning to Abhay: “Why don’t you come up here and speak instead of me?” Abhay was outwardly mortified, yet he treasured the rebuke.

| | Una vez en una habitación con muchos discípulos, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī estaba hablando y Abhay escuchaba cuando un anciano junto a Abhay le hizo señas. Cuando Abhay se inclinó para escuchar lo que el hombre quería, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta repentinamente habló molesto a los dos estudiantes aparentemente desatentos. “Bābū", se dirigió por primera vez al anciano junto a Abhay, “¿crees que me has comprado con tu donación de 150 rupias por mes?” Y luego, volviéndose hacia Abhay: “¿Por qué no vienes aquí y hablas en mi lugar?” Abhay estaba mortificado exteriormente, pero atesoró la reprimenda.

|  | It was in a private meeting that Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta once told Abhay of the risks he took by preaching so boldly.

| | Fue en una reunión privada que Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta le comentó una vez a Abhay sobre los riesgos que corría al predicar con tanta audacia.

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda: My Guru Mahārāja’s contribution is that he defeated the caste gosvāmīs. He defeated this Brahmanism. He did it the same way as Caitanya Mahāprabhu did. As Caitanya Mahāprabhu said, kibā vipra, kibā nyāsī, śūdra kene naya/ yei kṛṣṇa-tattva-vettā, sei ‘guru’ haya: “There is no consideration whether one is a sannyāsī, a brāhmaṇa, a śūdra, or a gṛhastha. No. Anyone who knows the science of Kṛṣṇa, he is all right, he is gosvāmī, and he is brāhmaṇa.”

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda: La contribución de mi Guru Mahārāja es que derrotó a la casta de los gosvāmīs. Él derrotó a este brahmanismo. Lo hizo de la misma manera que Caitanya Mahāprabhu. Como dijo Caitanya Mahāprabhu, kibā vipra, kibā nyāsī, śūdra kene naya / yei kṛṣṇa-tattva-vettā, sei ‘guru’ haya: “No se tiene en cuenta si uno es un sannyāsī, un brāhmaṇa, un śūdra o un gṛhastha. No. Cualquiera que conozca la ciencia de Kṛṣṇa, está bien, es gosvāmī y es brāhmaṇa".

|  | But no one else taught that since Lord Caitanya. This was my Guru Mahārāja’s contribution. And for this reason, he had to face so many vehement protests from these brāhmaṇa-caste gosvāmīs.

| | Pero nadie más enseñó eso desde el Señor Caitanya. Esta fue la contribución de mi Guru Mahārāja. Y por esta razón, tuvo que enfrentar tantas protestas vehementes de estos gosvāmīs brāhmaṇas de casta.

|  | Once they conspired to kill him – my Guru Mahārāja told me personally. By his grace, when we used to meet alone he used to talk about so many things. He was so kind that he used to talk with me, and he personally told me that these people, “They wanted to kill me.”

| | Una vez conspiraron para matarlo, mi Guru Mahārāja me lo dijo personalmente. Por su gracia, cuando solíamos encontrarnos solos, él hablaba de tantas cosas. Era tan amable que solía hablar conmigo, personalmente me dijo que estas personas “querían matarlo".

|  | They collected twenty-five thousand rupees and went to bribe the police officer in charge of the area, saying, “You take these twenty-five thousand rupees. We shall do something against Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, and you don’t take any steps.” He could understand that they wanted to kill him. So the police officer frankly came to Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī: “Of course, we accept bribes, and we indulge in such things, but not for a sādhu, not for a saintly person. I cannot dare.” So, the police officer refused and said to my Guru Mahārāja, “You take care. This is the position.” So vehemently they protested!

| | Colectaron veinticinco mil rupias y fueron a sobornar al oficial de policía a cargo del área, diciendo: “Toma estas veinticinco mil rupias. Haz algo contra Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī y no escatimes ninguna medida". Podía entender que querían matarlo. Entonces, el oficial de policía fue directamente ante Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī: “Por supuesto, aceptamos sobornos y nos entregamos a tales cosas, pero no para un sādhu, no para una persona santa. No me puedo atrever. Entonces, el oficial de policía se negó y le dijo a mi Guru Mahārāja: “Cuídate. Esta es la situación". ¡Tan vehementemente protestaron!

|  | But he liked boldness in his disciples. Abhay heard of an occasion when one of Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī’s disciples had been very outspoken at a public meeting and had denounced a highly regarded Māyāvādī monk as “a foolish priest.” The remark had caused a disruption at the meeting, and some of the disciples reported the incident to Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta, thinking he would be displeased that his disciple had caused a disturbance. But Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta was pleased and remarked, “He has done well.” His displeasure occurred, rather, when he heard of someone’s compromise.

| | Pero le gustaba la audacia en sus discípulos. Abhay se enteró de una ocasión en que uno de los discípulos de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī había sido muy franco en una reunión pública y había denunciado a un monje māyāvādī considerado como. “un sacerdote tonto". La observación había causado la interrupción de la reunión, algunos de los discípulos informaron el incidente a Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta, pensando que le disgustaría que su discípulo hubiera causado un disturbio. Pero Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta se mostró complacido y comentó: “Lo ha hecho bien". Su disgusto ocurrió, más bien, cuando escuchó sobre el compromiso de alguien.

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda: When my Guru Mahārāja was present, even big, big scholars were afraid to talk with even his beginning students. My Guru Mahārāja was called “living encyclopedia.” He could talk with anyone on any subject, he was so learned. And no compromise. So-called saints, avatāras, yogīs – everyone who was false was an enemy to my Guru Mahārāja. He never compromised. Some Godbrothers complained that this preaching was a “chopping technique” and it would not be successful. But those who criticized him fell down.

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda: Cuando mi Guru Mahārāja estaba presente, incluso los grandes, grandes eruditos tenían miedo de hablar inclusive con sus alumnos principiantes. Mi Guru Mahārāja fue llamado “enciclopedia viviente". Podía hablar con cualquier persona sobre cualquier tema, era muy erudito. Sin comprometerse. Los llamados santos, avatāras, yogīs: todos los que eran falsos eran enemigos de mi Guru Mahārāja. Nunca se comprometió. Algunos hermanos espirituales se quejaron de que esta prédica era una “técnica de corte” y que no sería exitosa. Pero los que lo criticaron se cayeron.

|  | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta was known as the siṁha (“lion”) guru. On occasion, when he saw someone he knew to be a proponent of impersonalism, he would call that person over and challenge: “Why are you cheating the people with Māyāvādī philosophy?” He would often tell his disciples not to compromise. “Why should you go flatter?” he would say. “You should speak the plain truth, without any flattery. Money will come anyway.”

| | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta era conocido como el siṁha ("león") guru. En ocasiones, cuando veía a alguien conocido como defensor del impersonalismo, llamaba a esa persona y lo desafiaba: “¿Por qué engañas a las personas con la filosofía māyāvādī?” A menudo les decía a sus discípulos que no se comprometieran. “¿Por qué deberías halagar?” él decía. “Debes decir la verdad, sin ningún tipo de adulación. El dinero vendrá de todos modos.

|  | Whenever Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta wrote or spoke the Vaiṣṇava philosophy, he was uncompromising; the conclusion was according to the śāstra, and the logic strong. But sometimes Abhay would hear his spiritual master express the eternal teachings in a unique way that Abhay knew he would never forget. “Don’t try to see God,” Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta would say, “but act in such a way that God sees you.”

| | Cada vez que Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta escribió o habló la filosofía vaiṣṇava, fue intransigente; la conclusión estaba de acuerdo con el śāstra y la lógica contundente. Pero a veces Abhay escuchaba a su maestro espiritual expresar las enseñanzas eternas de una manera única que Abhay sabía que nunca olvidaría. “No trates de ver a Dios", diría Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta, “sino actúa de tal manera que Dios te vea".

|  | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta condemned temple proprietors who made a business of showing the Deity for a living. To be a sweeper in the street was more honorable, he said. He coined a Bengali phrase, śālagrām-dvārā bādāṁ bhaṅga: “The priests are taking the śālagrāma Deity as a stone for cracking nuts.” In other words, if a person shows the śālagrāma form of the Lord (or any form of the Deity) simply with a view to make money, then he is seeing the Deity not as the Lord but as a stone, a means for earning his livelihood.

| | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta condenó a los propietarios de templos que se dedicaban a mostrar a la Deidad para ganarse la vida. Ser barrendero en la calle es más honorable, dijo. Él acuñó una frase bengalí, śālagrām-dvārā bādāṁ bhaṅga: “Los sacerdotes están tomando a la Deidad śālagrāma como una piedra para romper nueces". En otras palabras, si una persona muestra la forma śālagrāma del Señor (o cualquier forma de la Deidad) simplemente con el fin de ganar dinero, entonces está viendo a la Deidad no como el Señor sino como una piedra, un medio para ganar su sustento.

|  | Abhay had the opportunity to see his spiritual master deal with the nationalist Subhas Chandra Bose, who had been Abhay’s schoolmate at Scottish Churches’ College. Bose had come in a somewhat critical mood, concerned about Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta’s recruiting young men into religious life.

| | Abhay tuvo la oportunidad de ver la reunión de su maestro espiritual con el nacionalista Subhas Chandra Bose, quien había sido compañero de escuela de Abhay en el Colegio de Iglesias de Escocia. Bose había venido con un humor algo crítico, preocupado por el hecho de que Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta reclutara hombres jóvenes para la vida religiosa.

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda: Subhas Chandra Bose came to my Guru Mahārāja and said, “So many people you have captured. They are doing nothing for nationalism.”

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda: Subhas Chandra Bose fue con mi Guru Mahārāja y le dijo: “Tantas personas has atraído. No están haciendo nada por el nacionalismo".

|  | My Guru Mahārāja replied, “Well, for your national propaganda you require very strong men, but these people are very weak. You can see, they are very skinny. So don’t put your glance upon them. Let them eat something and chant Hare Kṛṣṇa.” In this way he avoided him.

| | Mi Guru Mahārāja respondió: “Bueno, para tu propaganda nacional necesitas hombres muy fuertes, pero estas personas son muy débiles. Puedes ver, son muy flacos. Así que no los veas. Permíteles comer algo y cantar Hare Kṛṣṇa”, de esta manera lo evitó.

|  | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta used to say that when the day came when high court judges were devotees of Kṛṣṇa with Vaiṣṇava tilaka on their foreheads, then he would know that the mission of spreading Kṛṣṇa consciousness was becoming successful.

| | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta solía decir que cuando llegara el día en que los jueces de los tribunales superiores fueran devotos de Kṛṣṇa con tilaka vaiṣṇava en la frente, entonces sabría que la misión de difundir la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa se estaba volviendo exitosa.

|  | He said that Jesus Christ was a śaktyāveśa-avatāra, an empowered incarnation of God. “How can it be otherwise?” he said. “He sacrificed everything for God.”

| | Dijo que Jesucristo era un śaktyāveśa-avatāra, una encarnación de Dios empoderada. “¿Cómo puede ser de otra manera?,” dijo, “él sacrificó todo por Dios".

|  | In his scholarly language he declared, “The materialistic demeanor cannot possibly stretch to the transcendental autocrat.” But sometimes in speech he phrased it in a more down-to-earth way: “The mundane scholars who are trying to understand the Supreme Lord by their senses and mental speculation are like a person trying to taste the honey in a bottle by licking the outside of the bottle.” Philosophy without religion, he said, is dry speculation; and religion without philosophy is sentiment and sometimes fanaticism.

| | En su lenguaje académico declaró: “El comportamiento materialista no puede extenderse al autócrata trascendental". Pero en ocasiones lo expresó de una manera más realista: “Los eruditos mundanos que están tratando de entender al Señor Supremo con sus sentidos y la especulación mental son como una persona que trata de saborear la miel en una botella lamiendo por fuera de la botella". Dijo: la filosofía sin religión es una mera especulación; y la religión sin filosofía es sentimentalismo y a veces, fanatismo.

|  | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta said that the whole world was simply a society of cheaters and cheated. He gave the example that loose women often visit certain holy places in India with the idea of seducing the sādhus, thinking that to have a child by a sādhu is prestigious. And immoral men dress themselves as sādhus, hoping to be seduced by the cheating women. His conclusion: a person should aspire to leave the material world and go back to Godhead, because “this material world is not a fit place for a gentleman.”