|

Śrīla Prabhupāda Līlambṛta - — Śrīla Prabhupāda Līlambṛta

Volume I — A lifetime in preparation — Volumen I — Toda una vida en preparación

<< 3 A Very Nice Saintly Person >> — << 3 Una persona santa muy agradable >>

| “There has not been, there will not be, such benefactors of the highest merit as [Caitanya] Mahaprabhu and His devotees have been. The offer of other benefits is only a deception; it is rather a great harm, whereas the benefit done by Him and His followers is the truest and greatest eternal benefit. This benefit is not for one particular country, causing mischief to another; but it benefits the whole universe.”

— Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī

| | “No ha habido, no habrá, tales benefactores del más alto mérito como lo han sido [Caitanya] Mahaprabhu y Sus devotos. La oferta de otros beneficios es solo un engaño; es más bien un gran daño, mientras que el beneficio hecho por Él y sus seguidores es el más verdadero y más grande beneficio eterno. Este beneficio no es para un país en particular, causando daño a otro; sino que beneficia a todo el universo.”

— Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī

|  | ABHAY’S FRIEND NARENDRANATH Mullik was insistent. He wanted Abhay to see a sādhu from Māyāpur. Naren and some of his friends had already met the sādhu at his nearby āśrama on Ultadanga Junction Road, and now they wanted Abhay’s opinion. Everyone within their circle of friends considered Abhay the leader, so if Naren could tell the others that Abhay also had a high regard for the sādhu, then that would confirm their own estimations. Abhay was reluctant to go, but Naren pressed him.

| | EL AMIGO DE ABHAY NARENDRANATH Mullik insistió. Quería que Abhay viera a un sādhu de Māyāpur. Naren y algunos de sus amigos ya habían conocido al sādhu en su āśrama cercano en El Crucero de la Calle Ultadanga, ahora querían la opinión de Abhay. Todos dentro de su círculo de amigos consideraban a Abhay el líder, por lo que si Naren podía decirle a los demás que Abhay también tenía un gran respeto por el sādhu, eso confirmaría sus propias estimaciones. Abhay se mostró reacio a ir, pero Naren lo presionó.

|  | They stood talking amidst the passersby on the crowded early-evening street, as the traffic of horse-drawn hackneys, oxcarts, and occasional auto taxis and motor buses moved noisily on the road. Naren put his hand firmly around his friend’s arm, trying to drag him forward, while Abhay smiled but stubbornly pulled the other way. Naren argued that since they were only a few blocks away, they should at least pay a short visit. Abhay laughed and asked to be excused. People could see that the two young men were friends, but it was a curious sight, the handsome young man dressed in white khādī kurtā and dhotī being pulled along by his friend.

| | Estaban de pie hablando entre los transeúntes en la concurrida calle a primera hora de la tarde, mientras el tráfico de coches de caballos, carretas tiradas por bueyes, ocasionalmente auto-taxis y autobuses a motor se movía ruidosamente por la carretera. Naren puso su mano firmemente alrededor del brazo de su amigo, tratando de arrastrarlo hacia adelante, mientras Abhay sonreía pero obstinadamente tiraba hacia el otro lado. Naren argumentó que, dado a que estaban a solo unas cuadras de distancia, al menos deberían hacer una breve visita. Abhay se rió y pidió que lo excusaran. La gente podía ver que los dos jóvenes eran amigos, pero era un espectáculo curioso, el apuesto joven vestido con khādī kurtā blanca y dhotī siendo arrastrado por su amigo.

|  | Naren explained that the sādhu, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, was a Vaiṣṇava and a great devotee of Lord Caitanya Mahāprabhu. One of his disciples, a sannyāsī, had visited the Mullik house and had invited them to meet Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta. A few of the Mulliks had gone to see him and had been very much impressed.

| | Naren explicó que el sādhu, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, era un vaiṣṇava y un gran devoto del Señor Caitanya Mahāprabhu. Uno de sus discípulos, un sannyāsī, visitó la casa de Mullik y los invitó a conocer a Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta. Algunos de los Mullik fueron a verlo y quedaron muy impresionados.

|  | But Abhay remained skeptical. Oh, no! I know all these sādhus, he said. I’m not going. Abhay had seen many sādhus in his childhood; every day his father had entertained at least three or four in his home. Some of them were no more than beggars, and some even smoked gāñjā. Gour Mohan had been very liberal in allowing anyone who wore the saffron robes of a sannyāsī to come. But did it mean that though a man was no more than a beggar or gāñjā smoker, he had to be considered saintly just because he dressed as a sannyāsī or was collecting funds in the name of building a monastery or could influence people with his speech?

| | Pero Abhay se mantuvo escéptico. ¡Oh, no! Conozco a todos estos sadhus, dijo. Yo no voy. Abhay había visto muchos sadhus en su infancia; todos los días su padre recibió por lo menos a tres o cuatro en su casa. Algunos de ellos no eran más que mendigos, algunos incluso fumaban gāñjā. Gour Mohan fue muy generoso al permitir que llegara cualquiera que vistiera las túnicas color azafrán de un sannyāsī. Pero, ¿significaba eso que aunque un hombre no era más que un mendigo o un fumador de gāñjā, tenía que ser considerado santo solo porque vestía como un sannyāsī o estaba recaudando fondos en nombre de la construcción de un monasterio o podía influir en las personas con su discurso?

|  | No. By and large, they were a disappointing lot. Abhay had even seen a man in his neighborhood who was a beggar by occupation. In the morning, when others dressed in their work clothes and went to their jobs, this man would put on saffron cloth and go out to beg and in this way earn his livelihood. But was it fitting that such a so-called sādhu be paid a respectful visit, as if he were a guru?

| | No. En general, fueron un grupo decepcionante. Abhay incluso vio a un hombre en su vecindario que era mendigo por ocupación. Por la mañana, cuando los demás se vestían con su ropa de trabajo y se dirigían a sus trabajos, este hombre se ponía ropa color azafrán y salía a mendigar para así ganarse la vida. Pero, ¿es apropiado que tal supuesto sādhu se le haga una visita respetuosa, como si fuera un guru?

|  | Naren argued that he felt that this particular sādhu was a very learned scholar and that Abhay should at least meet him and judge for himself. Abhay wished that Naren would not behave this way, but finally he could no longer refuse his friend. Together they walked past the Parsnath Jain Temple to 1 Ultadanga, with its sign, Bhaktivinod Asana, announcing it to be the quarters of the Gauḍīya Maṭh.

| | Naren argumentó que sentía que este sādhu en particular era un gran erudito y que Abhay debería al menos conocerlo y juzgar por sí mismo. Abhay deseaba que Naren no se comportara de esa manera, pero finalmente ya no pudo rechazar a su amigo. Juntos pasaron junto al templo Parsnath Jain hasta el 1 de la Calle Ultadanga, con su cartel, Bhaktivinod Asana, anunciando que era el recinto de la Gauḍīya Maṭh.

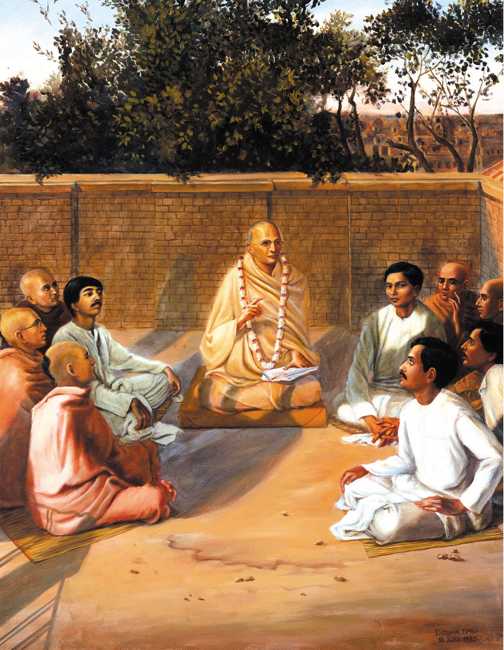

|  | When they inquired at the door, a young man recognized Mr. Mullik – Naren had previously given a donation – and immediately escorted them up to the roof of the second floor and into the presence of Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, who was sitting and enjoying the early evening atmosphere with a few disciples and guests.

| | Cuando preguntaron en la puerta, un joven reconoció al Sr. Mullik – Naren previamente hizo una donación – e inmediatamente los acompañó al techo del segundo piso ante la presencia de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, quien estaba sentado y disfrutando de las primeras horas de la tarde con algunos discípulos e invitados.

|  | Sitting with his back very straight, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī appeared tall. He was slender, his arms were long, and his complexion was fair and golden. He wore round bifocals with simple frames. His nose was sharp, his forehead broad, and his expression was very scholarly yet not at all timid. The vertical markings of Vaiṣṇava tilaka on his forehead were familiar to Abhay, as were the simple sannyāsa robes that draped over his right shoulder, leaving the other shoulder and half his chest bare. He wore tulasī neck beads, and the clay Vaiṣṇava markings of tilaka were visible at his throat, shoulder, and upper arms. A clean white brahminical thread was looped around his neck and draped across his chest. Abhay and Naren, having both been raised in Vaiṣṇava families, immediately offered prostrated obeisances at the sight of the revered sannyāsī.

| | Sentado con la espalda muy recta, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī parecía alto. Era delgado, sus brazos eran largos, su tez era clara y dorada. Usaba lentes bifocales redondos con marcos sencillos. Su nariz era afilada, su frente amplia, su expresión era muy estudiosa pero nada tímida. Las marcas verticales del tilaka Vaiṣṇava en su frente le eran familiares a Abhay, al igual que la sencilla túnica de sannyāsa que cubrían su hombro derecho, dejando el otro hombro y la mitad de su pecho desnudos. Llevaba cuentas de tulasī en el cuello, las marcas vaiṣṇavas de arcilla de tilaka eran visibles en la garganta, los hombros y la parte superior de los brazos. Un hilo brahmínico blanco y limpio estaba enrollado alrededor de su cuello y envuelto a través de su pecho. Abhay y Naren, ambos criados en familias vaiṣṇavas, inmediatamente ofrecieron reverencias postradas al ver al reverenciado sannyāsī.

|  | While the two young men were still rising and preparing to sit, before any preliminary formalities of conversation had begun, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta immediately said to them, You are educated young men. Why don’t you preach Lord Caitanya Mahāprabhu’s message throughout the whole world?

| | Mientras los dos jóvenes aún estaban de pie y preparándose para sentarse, antes de que comenzaran las formalidades preliminares de la conversación, Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta les dijo de inmediato: Ustedes son jóvenes educados. ¿Por qué no predican el mensaje del Señor Caitanya Mahāprabhu por todo el mundo?

|  | Abhay could hardly believe what he had just heard. They had not even exchanged views, yet this sādhu was telling them what they should do. Sitting face to face with Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, Abhay was gathering his wits and trying to gain a comprehensible impression, but this person had already told them to become preachers and go all over the world!

| | Abhay apenas podía creer lo que acababa de escuchar. Ni siquiera habían intercambiado puntos de vista, pero este sādhu les estaba diciendo lo que debían hacer. Sentado cara a cara con Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, Abhay estaba reuniendo su ingenio trataba de obtener una impresión comprensible, ¡pero esta persona ya les había dicho que se convirtieran en predicadores y que fueran por todo el mundo!

|  | Abhay was immediately impressed, but he wasn’t going to drop his intelligent skepticism. After all, there were assumptions in what the sādhu had said. Abhay had already announced himself by his dress to be a follower of Gandhi, and he felt the impulse to raise an argument. Yet as he continued to listen to Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta speak, he also began to feel won over by the sādhu’s strength of conviction. He could sense that Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta didn’t care for anything but Lord Caitanya and that this was what made him great. This was why followers had gathered around him and why Abhay himself felt drawn, inspired, and humbled and wanted to hear more. But he felt obliged to make an argument – to test the truth.

| | Abhay quedó inmediatamente impresionado, pero no iba a abandonar su inteligente escepticismo. Después de todo, había suposiciones en lo que dijo el sādhu. Abhay ya se anunció por su vestimenta como seguidor de Gandhi y sintió el impulso de plantear una discusión. Sin embargo, mientras continuaba escuchando hablar a Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta, también comenzó a sentirse conquistado por la fuerza de convicción del sādhu. Podía sentir que a Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta no le importaba nada más que el Señor Caitanya y que eso era lo que lo hacía grande. Esta fue la razón por la que los seguidores se reunieron a su alrededor y por la que el propio Abhay se sintió atraído, inspirado y humillado. Quería escuchar más, pero se sintió obligado a presentar un argumento, para probar la verdad.

|  | Drawn irresistibly into discussion, Abhay spoke up in answer to the words Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta had so tersely spoken in the first seconds of their meeting. Who will hear your Caitanya’s message? Abhay queried. We are a dependent country. First India must become independent. How can we spread Indian culture if we are under British rule?

| | Arrastrado irresistiblemente a la discusión, Abhay habló en respuesta a las palabras que Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta había pronunciado tan lacónicamente en los primeros segundos de su encuentro. ¿Quién escuchará el mensaje de tu Caitanya? preguntó Abhay. Somos un país dependiente. Primero India debe independizarse. ¿Cómo podremos difundir la cultura india si estamos bajo el dominio británico?

|  | Abhay had not asked haughtily, just to be provocative, yet his question was clearly a challenge. If he were to take this sādhu’s remark to them as a serious one – and there was nothing in Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta’s demeanor to indicate that he had not been serious – Abhay felt compelled to question how he could propose such a thing while India was still dependent.

| | Abhay no había preguntado con arrogancia solo para ser provocativo, pero su pregunta era claramente un desafío. Si él fuera a tomar el comentario de este sādhu como algo serio – y no había nada en el comportamiento de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta que indicara que no fuera en serio – Abhay se sintió obligado a preguntarse cómo podía proponer tal cosa mientras la India aún era dependiente.

|  | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta replied in a quiet, deep voice that Kṛṣṇa consciousness didn’t have to wait for a change in Indian politics, nor was it dependent on who ruled. Kṛṣṇa consciousness was so important – so exclusively important – that it could not wait.

| | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta respondió con voz tranquila y profunda que la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa no tiene que esperar un cambio en la política india, ni depende de quién gobierne. La Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa es tan importante, tan exclusivamente importante, que no puede esperar.

|  | Abhay was struck by his boldness. How could he say such a thing? The whole world of India beyond this little Ultadanga rooftop was in turmoil and seemed to support what Abhay had said. Many famous leaders of Bengal, many saints, even Gandhi himself, men who were educated and spiritually minded, all might very well have asked this same question, challenging this sādhu’s relevancy. And yet he was dismissing everything and everyone as if they were of no consequence.

| | Abhay quedó impresionado por su audacia. ¿Cómo podía decir tal cosa? Todo el mundo de la India más allá de este pequeño tejado de Ultadanga estaba conmocionado y parecía apoyar lo que dijo Abhay. Muchos líderes famosos de Bengala, muchos santos, incluso el propio Gandhi, hombres educados y de mente espiritual, muy bien podrían haber hecho esta misma pregunta, desafiando la relevancia de este sādhu. Sin embargo, estaba descartando todo y a todos como si no tuvieran importancia.

|  | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta continued: Whether one power or another ruled was a temporary situation; but the eternal reality is Kṛṣṇa consciousness, and the real self is the spirit soul. No man-made political system, therefore, could actually help humanity. This was the verdict of the Vedic scriptures and the line of spiritual masters. Although everyone is an eternal servant of God, when one takes himself to be the temporary body and regards the nation of his birth as worshipable, he comes under illusion. The leaders and followers of the world’s political movements, including the movement for svarāj, were simply cultivating this illusion. Real welfare work, whether individual, social, or political, should help prepare a person for his next life and help him reestablish his eternal relationship with the Supreme.

| | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta continuó: Que un poder u otro gobierne es una situación temporal; la realidad eterna es la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa, el yo real es el alma espiritual. Por lo tanto, ningún sistema político creado por el hombre podrá ayudar realmente a la humanidad. Este es el veredicto de las escrituras védicas y de la línea de maestros espirituales. Aunque todos son sirvientes eternos de Dios, cuando uno se toma a sí mismo como el cuerpo temporal y considera que la nación de su nacimiento es digna de adoración, cae en la ilusión. Los líderes y seguidores de los movimientos políticos del mundo, incluido el movimiento por svarāj, simplemente están cultivando esta ilusión. El verdadero trabajo de bienestar, ya sea individual, social o político, debe ayudar a preparar a una persona para su próxima vida y ayudarla a restablecer su relación eterna con el Supremo.

|  | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī had articulated these ideas many times before in his writings:

| | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī articuló estas ideas muchas veces antes en sus escritos:

|  | “There has not been, there will not be, such benefactors of the highest merit as [Caitanya] Mahaprabhu and His devotees have been. The offer of other benefits is only a deception; it is rather a great harm, whereas the benefit done by Him and His followers is the truest and greatest eternal benefit... This benefit is not for one particular country causing mischief to another; but it benefits the whole universe... The kindness that Śrī Caitanya Mahaprabhu has shown to jivas absolves them eternally from all wants, from all inconveniences and from all the distresses... That kindness does not produce any evil, and the jivas who have it will not be the victims of the evils of the world.”

| | «No ha habido, ni habrá, tales benefactores del más alto mérito como lo han sido [Caitanya] Mahaprabhu y Sus devotos. La oferta de otros beneficios es solo un engaño; es más bien un gran daño, mientras que el beneficio hecho por Él y sus seguidores es el más verdadero y más grande beneficio eterno... Este beneficio no es para un país en particular causando daño a otro; sino que beneficia a todo el universo... La bondad que Śrī Caitanya Mahaprabhu ha mostrado a las jivas las absuelve eternamente de todas las necesidades, de todos los inconvenientes y de todas las angustias... Esa bondad no produce ningún mal y las jivas que la tienen no serán víctimas de los males del mundo».

|  | As Abhay listened attentively to the arguments of Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, he recalled a Bengali poet who had written that even less advanced civilizations, like China and Japan, were independent and yet India labored under political oppression. Abhay knew well the philosophy of nationalism, which stressed that Indian independence had to come first. An oppressed people was a reality, the British slaughter of innocent citizens was a reality, and independence would benefit people. Spiritual life was a luxury that could be afforded only after independence. In the present times, the cause of national liberation from the British was the only relevant spiritual movement. The people’s cause was in itself God.

| | Mientras Abhay escuchaba atentamente los argumentos de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, recordó a un poeta bengalí que escribió que incluso las civilizaciones menos avanzadas, como la china y la japonesa, son independientes, sin embargo, la India sufría opresión política. Abhay conocía bien la filosofía del nacionalismo, que enfatizaba que la independencia india tenía que ser lo primero. Un pueblo oprimido era una realidad, la matanza británica de ciudadanos inocentes era una realidad y la independencia beneficiaría a la gente. La vida espiritual era un lujo que solo podía permitirse después de la independencia. En los tiempos actuales, la causa de la liberación nacional de los británicos era el único movimiento espiritual relevante. La causa del pueblo era en sí mismo Dios.

|  | Yet because Abhay had been raised a Vaiṣṇava, he appreciated what Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta was saying. Abhay had already concluded that this was certainly not just another questionable sādhu, and he perceived the truth in what Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta said. This sādhu wasn’t concocting his own philosophy, and he wasn’t simply proud or belligerent, even though he spoke in a way that kicked out practically every other philosophy. He was speaking the eternal teachings of the Vedic literature and the sages, and Abhay loved to hear it.

| | Sin embargo, debido a que Abhay fue criado como vaiṣṇava, apreció lo que Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta estaba diciendo. Abhay ya había llegado a la conclusión de que ciertamente no se trataba simplemente de otro sādhu cuestionable, percibió la verdad en lo que dijo Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta. Este sādhu no estaba inventando su propia filosofía, y no era simplemente orgulloso o beligerante, a pesar de que hablaba de una manera que eliminaba prácticamente todas las demás filosofías. Estaba hablando de las enseñanzas eternas de la literatura védica y de los sabios y a Abhay le encantaba escucharlas.

|  | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta, speaking sometimes in English and sometimes in Bengali, and sometimes quoting the Sanskrit verses of the Bhagavad-gītā, spoke of Śrī Kṛṣṇa as the highest Vedic authority. In the Bhagavad-gītā Kṛṣṇa had declared that a person should give up whatever duty he considers religious and surrender unto Him, the Personality of Godhead (sarva-dharmān parityajya mām ekaṁ śaraṇaṁ vraja). And the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam confirmed the same thing. Dharmaḥ projjhita-kaitavo ’tra paramo nirmatsarāṇāṁ satām: all other forms of religion are impure and should be thrown out, and only bhāgavata-dharma, performing one’s duties to please the Supreme Lord, should remain. Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta’s presentation was so cogent that anyone who accepted the śāstras would have to accept his conclusion.

| | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta, hablando unas veces en inglés, otras en bengalí y algunas veces citando los versos sánscritos del Bhagavad-gītā, habló de Śrī Kṛṣṇa como la máxima autoridad védica. En el Bhagavad-gītā, Kṛṣṇa declaró que una persona debe abandonar cualquier deber que considere religioso y entregarse a Él, la Personalidad de Dios (sarva-dharmān parityajya mām ekaṁ śaraṇaṁ vraja). El Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam confirmó lo mismo. Dharmaḥ projjhita-kaitavo ’tra paramo nirmatsarāṇāṁ satām: todas las demás formas de religión son impuras y deben descartarse y solo debe permanecer el bhāgavata-dharma, el cumplimiento de los deberes de uno para complacer al Señor Supremo. La presentación de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta era tan convincente que cualquiera que aceptara los śāstras tendría que aceptar su conclusión.

|  | The people were now faithless, said Bhaktisiddhānta, and therefore they no longer believed that devotional service could remove all anomalies, even on the political scene. He went on to criticize anyone who was ignorant of the soul and yet claimed to be a leader. He even cited names of contemporary leaders and pointed out their failures, and he emphasized the urgent need to render the highest good to humanity by educating people about the eternal soul and the soul’s relation to Kṛṣṇa and devotional service.

| | La gente ahora era incrédula, dijo Bhaktisiddhānta, por lo tanto ya no creen que el servicio devocional pueda eliminar todas las anomalías, incluso en la escena política. Continuó criticando a cualquiera que fuera ignorante del alma y que, sin embargo, afirme ser un líder. Incluso citó nombres de líderes contemporáneos, señaló sus fallas y enfatizó la necesidad urgente de brindar el mayor bien a la humanidad al educar a las personas sobre el alma eterna, la relación del alma con Kṛṣṇa y el servicio devocional.

|  | Abhay had never forgotten the worship of Lord Kṛṣṇa or His teachings in Bhagavad-gītā. And his family had always worshiped Lord Caitanya Mahāprabhu, whose mission Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī was espousing. As these Gauḍīya Maṭh people worshiped Kṛṣṇa, he also had worshiped Kṛṣṇa throughout his life and had never forgotten Kṛṣṇa. But now he was astounded to hear the Vaiṣṇava philosophy presented so masterfully. Despite his involvement in college, marriage, the national movement, and other affairs, he had never forgotten Kṛṣṇa. But Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī was now stirring up within him his original Kṛṣṇa consciousness, and by the words of this spiritual master not only was he remembering Kṛṣṇa, but he felt his Kṛṣṇa consciousness being enhanced a thousand times, a million times. What had been unspoken in Abhay’s boyhood, what had been vague in Jagannātha Purī, what he had been distracted from at college, what he had been protected in by his father now surged forth within Abhay in responsive feelings. And he wanted to keep it.

| | Abhay nunca olvidó la adoración del Señor Kṛṣṇa o Sus enseñanzas del Bhagavad-gītā. Su familia siempre adoró al Señor Caitanya Mahāprabhu, cuya misión estaba adoptando Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī. Así como esta gente del Maṭh Gauḍīya adoraba a Kṛṣṇa, él también adoró a Kṛṣṇa durante toda su vida y nunca olvidó a Kṛṣṇa. Pero ahora estaba asombrado de escuchar la filosofía vaiṣṇava presentada de manera tan magistral. A pesar de su participación en la universidad, el matrimonio, el movimiento nacional y otros asuntos, nunca olvidó a Kṛṣṇa. Ahora Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī estaba despertando dentro de él su Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa original y por las palabras de este maestro espiritual no solo estaba recordando a Kṛṣṇa, sino que sentía que su Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa aumentaba mil veces, un millón de veces. Lo que no se dijo en la niñez de Abhay, lo que fue vago en Jagannātha Purī, aquello de lo que se distrajo en la universidad, aquello con lo que su padre lo protegió, ahora surgió dentro de Abhay en sentimientos de respuesta y quiso conservarlo.

|  | He felt himself defeated. But he liked it. He suddenly realized that he had never before been defeated. But this defeat was not a loss. It was an immense gain.

| | Se sintió derrotado. Pero le gustó. De repente se dio cuenta de que nunca antes había sido derrotado. Pero esta derrota no fue una pérdida. Fue una ganancia inmensa.

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda: I was from a Vaiṣṇava family, so I could appreciate what he was preaching. Of course, he was speaking to everyone, but he found something in me. And I was convinced about his argument and mode of presentation. I was so much struck with wonder. I could understand: Here is the proper person who can give a real religious idea.

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda: Yo era de una familia vaiṣṇava, así que podía apreciar lo que predicaba. Por supuesto, estaba hablando con todos, pero él encontró algo en mí y me convenció su argumento y modo de presentación. Estaba tan atónito. Pude entender: Aquí está la persona adecuada que puede dar una idea religiosa real.

|  | It was late. Abhay and Naren had been talking with him for more than two hours. One of the brahmacārīs gave them each a bit of prasādam in their open palms, and they rose gratefully and took their leave.

| | Era tarde. Abhay y Naren estuvieron hablando con él durante más de dos horas. Uno de los brahmacārīs le dio a cada uno un poco de prasādam en sus palmas abiertas, se levantaron agradecidos y se despidieron.

|  | They walked down the stairs and onto the street. The night was dark. Here and there a light was burning, and there were some open shops. Abhay pondered in great satisfaction what he had just heard. Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta’s explanation of the independence movement as a temporary, incomplete cause had made a deep impression on him. He felt himself less a nationalist and more a follower of Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī. He also thought that it would have been better if he were not married. This great personality was asking him to preach. He could have immediately joined, but he was married; and to leave his family would be an injustice.

| | Bajaron las escaleras y salieron a la calle. La noche era oscura. Aquí y allá ardía una luz y algunas tiendas abiertas. Abhay reflexionó con gran satisfacción sobre lo que acababa de escuchar. La explicación de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta del movimiento de independencia como una causa temporal e incompleta le causó una profunda impresión. Se sintió menos nacionalista y más seguidor de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī. También pensó que hubiera sido mejor si no estuviera casado. Esta gran personalidad le estaba pidiendo que predicara. Pudo haberse unido inmediatamente, pero estaba casado y dejar a su familia sería una injusticia.

|  | Walking away from the āśrama, Naren turned to his friend: “So, Abhay, what was your impression? What do you think of him?”

| | Alejándose del āśrama, Naren se volvió hacia su amigo: “Entonces, Abhay, ¿cuál fue tu impresión? ¿Qué piensas de él?"

|  | He’s wonderful! replied Abhay. The message of Lord Caitanya is in the hands of a very expert person.

| | ¡Es maravilloso! respondió Abhay. El mensaje del Señor Caitanya está en manos de una persona muy experta.

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda: I accepted him as my spiritual master immediately. Not officially, but in my heart. I was thinking that I had met a very nice saintly person.

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda: Lo acepté como mi maestro espiritual de inmediato. No oficialmente, sino en mi corazón. Estaba pensando que había conocido a una persona muy agradable y santa.

|  | After his first meeting with Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, Abhay began to associate more with the Gauḍīya Maṭh devotees. They gave him books and told him the history of their spiritual master.

| | Después de su primer encuentro con Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, Abhay comenzó a asociarse más con los devotos del Maṭh Gauḍīya. Le dieron libros y le contaron la historia de su maestro espiritual.

|  | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī was one of ten children born to Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura, a great Vaiṣṇava teacher in the disciplic line from Lord Caitanya Himself. Before the time of Bhaktivinoda, the teachings of Lord Caitanya had been obscured by teachers and sects falsely claiming to be followers of Lord Caitanya but deviating in various drastic ways from His pure teachings. The good reputation of Vaiṣṇavism had been compromised. Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura, however, through his prolific writings and through his social position as a high government officer, reestablished the respectability of Vaiṣṇavism. He preached that the teachings of Lord Caitanya were the highest form of theism and were intended not for a particular sect or religion or nation but for all the people of the world. He prophesied that Lord Caitanya’s teachings would go worldwide, and he yearned for it.

| | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī fue uno de los diez niños nacidos de Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura, un gran maestro vaiṣṇava en la línea discipular del mismo Señor Caitanya. Antes del tiempo de Bhaktivinoda, las enseñanzas del Señor Caitanya fueron obscurecidas por maestros y sectas que afirmaban falsamente ser seguidores del Señor Caitanya, pero que se desviaban de varias maneras drásticas de Sus enseñanzas puras. La buena reputación del vaisnavismo se cio comprometida. Sin embargo Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura a través de sus prolíficos escritos y a través de su posición social como alto funcionario del gobierno, restableció la respetabilidad del vaisnavismo. Predicó que las enseñanzas del Señor Caitanya son la forma más elevada de teísmo y que no están destinadas a una secta, religión o nación en particular, sino a todas las personas del mundo. Él profetizó que las enseñanzas del Señor Caitanya irían a todo el mundo y lo anhelaba.

|  | The religion preached by [Caitanya] Mahaprabhu is universal and not exclusive. … The principle of kirtan as the future church of the world invites all classes of men, without distinction of caste or clan, to the highest cultivation of the spirit. This church, it appears, will extend all over the world and take the place of all sectarian churches, which exclude outsiders from the precincts of the mosque, church, or temple.

| | La religión predicada por [Caitanya] Mahaprabhu es universal y no exclusiva... El principio del kirtan como la futura iglesia del mundo invita a todas las clases de hombres, sin distinción de casta o clan, al cultivo más elevado del espíritu. Aparentemente, esta iglesia se extenderá por todo el mundo y tomará el lugar de todas las iglesias sectarias, que excluyen a los forasteros de los recintos de la mezquita, iglesia o templo.

|  | Lord Caitanya did not advent Himself to liberate only a few men of India. Rather, His main objective was to emancipate all living entities of all countries throughout the entire universe and preach the Eternal Religion. Lord Caitanya says in the Caitanya Bhagwat: In every town, country, and village, My name will be sung. There is no doubt that this unquestionable order will come to pass. … Although there is still no pure society of Vaishnavas to be had, yet Lord Caitanya’s prophetic words will in a few days come true, I am sure. Why not? Nothing is absolutely pure in the beginning. From imperfection, purity will come about.

| | El advenimiento del Señor Caitanya no fue para liberar solo a unos pocos hombres de la India. Más bien, su objetivo principal fue emancipar a todas las entidades vivientes de todos los países en todo el universo y predicar la Religión Eterna. El Señor Caitanya dice en el Caitanya Bhagwat: En cada ciudad, país y pueblo, se cantará mi nombre. No hay duda de que esta incuestionable orden se cumplirá... Aunque todavía no hay una sociedad pura de vaisnavas, las palabras proféticas del Señor Caitanya se harán realidad un día, estoy seguro. ¿Por qué no? Nada es absolutamente puro al principio. De la imperfección, vendrá la pureza.

|  | Oh, for that day when the fortunate English, French, Russian, German, and American people will take up banners, mridangas, and kartals and raise kirtan through their streets and towns. When will that day come?

| | Oh, para ese día en que los afortunados ingleses, franceses, rusos, alemanes y estadounidenses llevarán pancartas, mridangas, kartalas y resucitarán el kirtan por sus calles y pueblos. ¿Cuándo vendrá ese día?

|  | As a prominent magistrate, Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura was a responsible government officer. He served also as superintendent of the temple of Lord Jagannātha and was the father of ten children. Yet in spite of these responsibilities, he served the cause of Kṛṣṇa with prodigious energy. After coming home from his office in the evening, taking his meals, and going to bed, he would sleep from eight until midnight and then get up and write until morning. He wrote more than one hundred books during his life, many of them in English. One of his important contributions, with the cooperation of Jagannātha dāsa Bābājī and Gaurakiśora dāsa Bābājī, was to locate the exact birthplace of Lord Caitanya in Māyāpur, about sixty miles north of Calcutta.

| | Como magistrado prominente, Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura fue un oficial responsable del gobierno. Sirvió también como superintendente del templo del Señor Jagannātha y fue padre de diez hijos. Sin embargo, a pesar de estas responsabilidades, sirvió a la causa de Kṛṣṇa con una energía prodigiosa. Después de llegar a casa desde su oficina en la noche, tomar sus comidas y acostarse, dormía desde las ocho hasta la medianoche y luego se levantaba y escribía hasta la mañana. Escribió más de cien libros durante su vida, muchos de ellos en inglés. Una de sus contribuciones más importantes, con la cooperación de Jagannātha dāsa Bābājī y Gaurakiśora dāsa Bābājī, fue localizar el lugar exacto del nacimiento del Señor Caitanya en Māyāpur, a unos 96 kilómetros al norte de Calcuta.

|  | While working to reform Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavism in India, he prayed to Lord Caitanya, Your teachings have been much depreciated. It is not in my power to restore them. And he prayed for a son to help him in his preaching. When, on February 6, 1874, Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī was born to Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura in Jagannātha Purī, the Vaiṣṇavas considered him the answer to his father’s prayers. He was born with the umbilical cord wrapped around his neck and draped across his chest like the sacred thread worn by brāhmaṇas. His parents gave him the name Bimala Prasada.

| | Mientras trabajaba para reformar el vaiṣṇavismo gauḍīya en India, rezó al Señor Caitanya: Tus enseñanzas se han depreciado mucho. No está en mi poder restaurarlas. Oró por un hijo que lo ayudara en su predica. Cuando, el 6 de febrero de 1874, Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī nació de Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura en Jagannātha Purī, los vaiṣṇavas lo consideraron la respuesta a las oraciones de su padre. Nació con el cordón umbilical envuelto alrededor de su cuello y envuelto en su pecho como el hilo sagrado que usan los brāhmaṇas. Sus padres le dieron el nombre de Bimala Prasada.

|  | When Bimala Prasada was six months old, the carts of the Jagannātha festival stopped at the gate of Bhaktivinoda’s residence and for three days could not be moved. Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura’s wife brought the infant onto the cart and approached the Deity of Lord Jagannātha. Spontaneously, the infant extended his arms and touched the feet of Lord Jagannātha and was immediately blessed with a garland that fell from the body of the Lord. When Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura learned that the Lord’s garland had fallen onto his son, he realized that this was the son for whom he had prayed.

| | Cuando Bimala Prasada tenía seis meses, los carruajes del festival de Jagannātha se detuvieron en la puerta de la residencia de Bhaktivinoda y durante tres días no se pudieron mover. La esposa de Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura llevó al bebé al carro y se acercó a la Deidad del Señor Jagannātha. Espontáneamente, el niño extendió los brazos y tocó los pies del Señor Jagannātha e inmediatamente fue bendecido con una guirnalda que cayó del cuerpo del Señor. Cuando Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura se enteró de que la guirnalda del Señor había caído sobre su hijo, se dio cuenta de que éste era el hijo por el que estuvo rezado.

|  | One day, when Bimala Prasada was still a child of no more than four years, his father mildly rebuked him for eating a mango not yet duly offered to Lord Kṛṣṇa. Bimala Prasada, although only a child, considered himself an offender to the Lord and vowed never to eat mangoes again. (This was a vow that he would follow throughout his life.) By the time Bimala Prasada was seven years old, he had memorized the entire Bhagavad-gītā and could even explain its verses. His father then began training him in proofreading and printing, in conjunction with the publishing of the Vaiṣṇava magazine Sajjana-toṣaṇī. With his father, he visited many holy places and heard discourses from the learned paṇḍitas.

| | Un día, cuando Bimala Prasada todavía era un niño de no más de cuatro años, su padre lo reprendió levemente por comer un mango que aún no se había ofrecido debidamente al Señor Kṛṣṇa. Bimala Prasada, aunque solo era un niño, se consideraba un delincuente del Señor y prometió no volver a comer mangos. (Este fue un voto que siguió durante toda su vida.) Cuando Bimala Prasada tenía siete años, memorizó todo el Bhagavad-gītā, incluso podía explicar sus versos. Luego, su padre comenzó a entrenarlo en la revisión y la impresión, junto con la publicación de la revista Vaiṣṇava Sajjana-toṣaṇī. Con su padre visitó muchos lugares sagrados y escuchó discursos de los sabios paṇḍitas.

|  | As a student, Bimala Prasada preferred to read the books written by his father instead of the school texts. By the time he was twenty-five he had become well versed in Sanskrit, mathematics, and astronomy, and he had established himself as the author and publisher of many magazine articles and one book, Sūrya-siddhānta, for which he received the epithet Siddhānta Sarasvatī in recognition of his erudition. When he was twenty-six his father guided him to take initiation from a renounced Vaiṣṇava saint, Gaurakiśora dāsa Bābājī, who advised him to preach the Absolute Truth and keep aside all other works. Receiving the blessings of Gaurakiśora dāsa Bābājī, Bimala Prasada (now Siddhānta Sarasvatī) resolved to dedicate his body, mind, and words to the service of Lord Kṛṣṇa.

| | Como estudiante, Bimala Prasada prefería leer los libros escritos por su padre en lugar de los textos escolares. Para cuando tenía veinticinco años ya era muy versado en sánscrito, matemáticas y astronomía y se había establecido como autor y editor de muchos artículos de revistas y un libro, Sūrya-siddhānta, por el cual recibió el epíteto Siddhānta Sarasvati en reconocimiento a su erudición. Cuando tenía veintiséis años, su padre lo guío a tomar la iniciación de un santo vaiṣṇava renunciado, Gaurakiśora dāsa Bābājī, quien le aconsejó predicar la Verdad Absoluta y dejar de lado todas las demás obras. Al recibir las bendiciones de Gaurakiśora dāsa Bābājī, Bimala Prasada (ahora Siddhānta Sarasvatī) decidió dedicar su cuerpo, mente y palabras al servicio del Señor Kṛṣṇa.

|  | In 1905 Siddhānta Sarasvatī took a vow to chant the Hare Kṛṣṇa mantra a billion times. Residing in Māyāpur in a grass hut near the birthplace of Lord Caitanya, he chanted the Hare Kṛṣṇa mantra day and night. He cooked rice once a day in an earthen pot and ate nothing more; he slept on the ground, and when the rainwater leaked through the grass ceiling, he sat beneath an umbrella, chanting.

| | En 1905, Siddhānta Sarasvatī hizo un voto para cantar el mantra Hare Kṛṣṇa mil millones de veces. Residiendo en Māyāpur en una choza de hierba cerca del lugar de nacimiento del Señor Caitanya, cantó el mantra Hare Kṛṣṇa día y noche. Cocinaba arroz una vez al día en una olla de barro y no comía nada más; dormía en el suelo, cuando el agua de lluvia se filtró a través del techo de hierba, se sentó debajo de un paraguas, cantando.

|  | In 1911, while his aging father was lying ill, Siddhānta Sarasvatī took up a challenge against pseudo Vaiṣṇavas who claimed that birth in their caste was the prerequisite for preaching Kṛṣṇa consciousness. The caste-conscious brāhmaṇa community had become incensed by Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura’s presentation of many scriptural proofs that anyone, regardless of birth, could become a brāhmaṇa Vaiṣṇava. These smārta-brāhmaṇas, out to prove the inferiority of the Vaiṣṇavas, arranged a discussion. On behalf of his indisposed father, young Siddhānta Sarasvatī wrote an essay, “The Conclusive Difference Between the Brāhmaṇa and the Vaiṣṇava,” and submitted it before his father. Despite his poor health, Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura was elated to hear the arguments that would soundly defeat the challenge of the smārtas.

| | En 1911, mientras su anciano padre estaba enfermo, Siddhānta Sarasvatī se enfrentó a los pseudo Vaiṣṇavas que afirmaban que el nacimiento en su casta era el requisito previo para predicar la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa. La comunidad de brāhmaṇas conciente de la casta se enfureció por la presentación de Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura de muchas pruebas escriturales de que cualquiera, independientemente de su nacimiento, puede convertirse en un brāhmaṇa vaiṣṇava. Estos smārta-brāhmaṇas, para demostrar la inferioridad de los vaiṣṇavas, organizaron una discusión. En nombre de su padre indispuesto, el joven Siddhānta Sarasvatī escribió un ensayo,. “La diferencia definitiva entre el Brāhmaṇa y el Vaiṣṇava.” lo presentó ante su padre. A pesar de su mala salud, Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura estaba eufórico al escuchar los argumentos que derrotarían el desafío de los smārtas.

|  | Siddhānta Sarasvatī then traveled to Midnapore, where paṇḍitas from all over India had gathered for a three-day discussion. Some of the smārta-paṇḍitas who spoke first claimed that anyone born in a śūdra family, even though initiated by a spiritual master, could never become purified and perform the brahminical duties of worshiping the Deity or initiating disciples. Finally, Siddhānta Sarasvatī delivered his speech. He began quoting Vedic references glorifying the brāhmaṇas, and at this the smārta scholars became very much pleased. But when he began discussing the actual qualifications for becoming a brāhmaṇa, the qualities of the Vaiṣṇavas, the relationship between the two, and who, according to the Vedic literature, is qualified to become a spiritual master and initiate disciples, then the joy of the Vaiṣṇava-haters disappeared. Siddhānta Sarasvatī conclusively proved from the scriptures that if one is born as a śūdra but exhibits the qualities of a brāhmaṇa, then he should be honored as a brāhmaṇa, despite his birth. And if one is born in a brāhmaṇa family but acts like a śūdra, then he is not a brāhmaṇa. After his speech, Siddhānta Sarasvatī was congratulated by the president of the conference, and thousands thronged around him. It was a victory for Vaiṣṇavism.

| | Luego Siddhānta Sarasvatī viajó a Midnapore, donde los paṇḍitas de toda la India se habían reunido para una disertación de tres días. Algunos de los smārta-paṇḍitas que hablaron primero afirmaron que cualquier persona nacida en una familia śūdra, aunque sea iniciada por un maestro espiritual, nunca podría purificarse y realizar los deberes brahmínicos de adorar a la Deidad o iniciar discípulos. Finalmente, Siddhānta Sarasvatī pronunció su discurso. Comenzó a citar referencias védicas que glorificaban a los brāhmaṇas, ante esto los eruditos smārta se sintieron muy complacidos. Pero cuando comenzó a discernir sobre las cualificaciones reales para convertirse en un brāhmaṇa, las cualidades de los vaiṣṇavas, la relación entre los dos y quién, según la literatura védica, está calificado para convertirse en un maestro espiritual e iniciar discípulos, entonces la alegría de los odiadores vaiṣṇavas desaparecieron. Siddhānta Sarasvatī demostró de manera concluyente a partir de las escrituras que si uno nace como un śūdra pero exhibe las cualidades de un brāhmaṇa, entonces debe ser honrado como un brāhmaṇa, a pesar de su nacimiento. Y que si uno nace en una familia brāhmaṇa pero actúa como un śūdra, entonces no es un brāhmaṇa. Después de su discurso, Siddhānta Sarasvatī fue felicitado por el presidente de la conferencia y miles se amontonaron a su alrededor. Fue una victoria para el vaisnavismo.

|  | With the passing away of his father in 1914 and his spiritual master in 1915, Siddhānta Sarasvatī continued the mission of Lord Caitanya. He assumed editorship of Sajjana-toṣaṇī and established the Bhagwat Press in Kṛṣṇanagar. Then in 1918, in Māyāpur, he sat down before a picture of Gaurakiśora dāsa Bābājī and initiated himself into the sannyāsa order. At this time he assumed the sannyāsa title Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Gosvāmī Mahārāja.

| | Con la muerte de su padre en 1914 y su maestro espiritual en 1915, Siddhānta Sarasvatī continuó la misión del Señor Caitanya. Asumió la dirección del Sajjana-toṣaṇī y estableció Bhagwat Press en Kṛṣṇanagar. Luego, en 1918, en Māyāpur, se sentó ante una imagen de Gaurakiśora dāsa Bābājī y se inició en la orden sannyāsa. En este momento asumió el título de sannyāsa Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Gosvāmī Mahārāja.

|  | Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī was dedicated to using the printing press as the best medium for large-scale distribution of Kṛṣṇa consciousness. He thought of the printing press as a bṛhad-mṛdaṅga, a big mṛdaṅga. Although the mṛdaṅga drum had traditionally been used to accompany kīrtana, even during the time of Lord Caitanya, and although Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī himself led kīrtana parties and sent groups of devotees chanting in the streets and playing on the mṛdaṅgas, such kīrtanas could be heard only for a block or two. But with the bṛhad-mṛdaṅga, the big mṛdaṅga drum of the printing press, the message of Lord Caitanya could be spread all over the world.

| | Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī se dedicó a utilizar la imprenta como el mejor medio para la distribución a gran escala de la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa. Pensaba en la imprenta como una bṛhad-mṛdaṅga, una gran mṛdaṅga. Aunque el tambor mṛdaṅga se usaba tradicionalmente para acompañar el kīrtana, incluso durante la época del Señor Caitanya y aunque el propio Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī dirigió fiestas de kīrtana y envió grupos de devotos cantando por las calles y tocando las mṛdaṅgas, tales kīrtanas solo podían escucharse por una cuadra o dos. Pero con el bṛhad-mṛdaṅga, el gran tambor mṛdaṅga de la imprenta, el mensaje del Señor Caitanya podría extenderse por todo el mundo.

|  | Most of the literature Abhay began reading had been printed on the Bhagwat Press, which Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī had established in 1915. The Bhagwat Press had printed the Caitanya-caritāmṛta, with commentary by Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, the Bhagavad-gītā, with commentary by Viśvanātha Cakravartī, and one after another, the works of Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura. This literature was the spiritual heritage coming from Lord Caitanya Mahāprabhu, who had appeared almost five hundred years before.

| | La mayor parte de la literatura que Abhay comenzó a leer fue impresa en la Bhagwat Press, que Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī estableció en 1915. La Bhagwat Press imprimió el Caitanya-caritāmṛta, con comentarios de Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, el Bhagavad-gītā, con comentarios de Viśvanātha Cakravartī y una tras otra, las obras de Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura. Esta literatura es la herencia espiritual proveniente del Señor Caitanya Mahāprabhu, quien apareció casi quinientos años atrás.

|  | Abhay had been a devotee of Lord Caitanya since childhood, and he was familiar with the life of Lord Caitanya through the well-known scriptures Caitanya-caritāmṛta and Caitanya-bhāgavata. He had learned of Lord Caitanya not only as the most ecstatic form of a pure devotee who had spread the chanting of the holy name to all parts of India, but also as the direct appearance of Śrī Kṛṣṇa Himself in the form of Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa combined. But now, for the first time, Abhay was in touch with the great wealth of literature compiled by the Lord’s immediate associates and followers, passed down in disciplic succession, and expanded on by great authorities. Lord Caitanya’s immediate followers – Śrīla Rūpa Gosvāmī, Śrīla Sanātana Gosvāmī, Śrīla Jīva Gosvāmī, and others – had compiled many volumes based on the Vedic scriptures and proving conclusively that Lord Caitanya’s teachings were the essence of Vedic wisdom. There were many books not yet published, but Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī was intent on establishing many presses, just to release the sound of the bṛhad-mṛdaṅga for the benefit of all people.

| | Abhay fue un devoto del Señor Caitanya desde la infancia, estaba familiarizado con la vida del Señor Caitanya a través de las conocidas escrituras Caitanya-caritāmṛta y el Caitanya-bhāgavata. Aprendió del Señor Caitanya no solo como la forma más extática de un devoto puro que extendió el canto del santo nombre a todas las partes de la India, sino también como la aparición directa de Śrī Kṛṣṇa mismo en forma de Rādhā y Kṛṣṇa combinados. Pero ahora, por primera vez, Abhay estaba en contacto con la gran riqueza de la literatura recopilada por los asociados y seguidores inmediatos del Señor, transmitida en sucesión discipular y ampliada por grandes autoridades. Los seguidores inmediatos del Señor Caitanya, Śrīla Rūpa Gosvāmī, Śrīla Sanātana Gosvāmī, Śrīla Jīva Gosvāmī y otros, compilaron muchos volúmenes basados en las escrituras védicas demostrando de manera concluyente que las enseñanzas del Señor Caitanya son la esencia de la sabiduría védica. Había muchos libros aún no publicados, pero Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī tenía la intención de establecer muchas imprentas, solo para liberar el sonido del bṛhad-mṛdaṅga en beneficio de todas las personas.

|  | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī was teaching the conclusion of Lord Caitanya’s teachings, that Lord Kṛṣṇa is the Supreme Personality of Godhead and that the chanting of His holy name should be stressed above all other religious practices. In former ages, other methods of attaining to God had been available, but in the present Age of Kali only the chanting of Hare Kṛṣṇa would be effective. On the authority of the scriptures such as the Bṛhan-nāradīya Purāṇa and the Upaniṣads, Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura had specifically cited the mahā-mantra: Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa, Hare Hare / Hare Rāma, Hare Rāma, Rāma Rāma, Hare Hare. Lord Kṛṣṇa Himself had confirmed in Bhagavad-gītā that the only method of attaining Him was devotional service: Abandon all varieties of religion and just surrender unto Me. I shall deliver you from all sinful reactions. Do not fear.

| | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī estaba enseñando la conclusión de las enseñanzas del Señor Caitanya, que el Señor Kṛṣṇa es la Suprema Personalidad de Dios y que el canto de Su santo nombre debe enfatizarse por encima de todas las demás prácticas religiosas. En épocas anteriores, otros métodos para alcanzar a Dios estuvieron disponibles, pero en la actual Era de Kali solo el canto del mahamantra Hare Kṛṣṇa es efectivo. Sobre la autoridad de las escrituras como Bṛhan-nāradīya Purāṇa y los Upaniṣads, Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura citó específicamente el mahā-mantra: Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa, Hare Hare / Hare Rāma, Hare Rāma, Rāma Rāma, Hare Hare. El mismo Señor Kṛṣṇa confirmó en el Bhagavad-gītā que el único método para alcanzarlo era el servicio devocional: Abandona todas las variedades de religión y simplemente ríndete a Mí. Te libraré de todas las reacciones pecaminosas. No temas.

|  | Abhay knew these verses, he knew the chanting, and he knew the conclusions of the Gītā. But now, as he eagerly read the writings of the great ācāryas, he had fresh realizations of the scope of Lord Caitanya’s mission. Now he was discovering the depth of his own Vaiṣṇava heritage and its efficacy for bringing about the highest welfare for people in an age destined to be full of troubles.

| | Abhay conocía estos versos, conocía el canto y conocía las conclusiones del Gītā. Pero ahora, mientras leía ansiosamente los escritos de los grandes ācāryas, tuvo una nueva comprensión del alcance de la misión del Señor Caitanya. Ahora estaba descubriendo la profundidad de su propia herencia vaiṣṇava y su eficacia para lograr el mayor bienestar para las personas en una época destinada a estar llena de problemas.

|  | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta was often traveling, and Abhay was busy with his family and business, so to arrange another meeting was not possible. Yet from their first encounter Abhay had considered Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī his spiritual master, and Abhay began thinking of him always, I have met such a nice saintly person. Whenever possible, Abhay would seek out Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta’s disciples, the members of the Gauḍīya Maṭh.

| | Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta viajaba con frecuencia y Abhay estaba ocupado con su familia y sus negocios, por lo que no fue posible organizar otra reunión. Sin embargo, desde su primer encuentro, Abhay consideró a Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī su maestro espiritual y Abhay comenzó a pensar en él siempre: He conocido a una persona tan agradable y santa. Siempre que sea posible, Abhay buscaría a los discípulos de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta, los miembros del Maṭh Gauḍīya.

|  | As for Gandhi’s movement, Gandhi had suffered a bitter setback when his nonviolent followers had blundered and committed violence during a protest. The British had taken the opportunity to arrest Gandhi and sentence him to six years in jail. Although his followers still revered him, the nationalist movement had lost much of its impetus. But regardless of that, Abhay was no longer interested. Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī had defeated his idea that the nationalist cause was India’s first priority. He had invoked Abhay’s original Kṛṣṇa consciousness, and Abhay now felt confident that Bhaktisiddhānta’s mission was the real priority. Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta had invited him to preach, and from that moment Abhay had wanted to join the Gauḍīya Maṭh as one of Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī’s disciples. But now, instead of his political inclinations, it was his family obligations that stood in the way. He was no longer thinking, First let us become an independent nation, then preach about Lord Caitanya. Now he was thinking, I cannot take part like the others. I have my family responsibilities.

| | En cuanto al movimiento de Gandhi, Gandhi sufrió un duro revés cuando sus seguidores no violentos hicieron un error y cometieron violencia durante una protesta. Los británicos aprovecharon la oportunidad para arrestar a Gandhi y condenarlo a seis años de cárcel. Aunque sus seguidores todavía lo veneraban, el movimiento nacionalista perdió gran parte de su ímpetu. Independientemente de eso, Abhay ya no estaba interesado. Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī derrotó su idea de que la causa nacionalista era la primera prioridad de la India. Invocó la conciencia original de Kṛṣṇa de Abhay y Abhay ahora confiaba en que la misión de Bhaktisiddhānta era la verdadera prioridad. Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta lo invitó a predicar y desde ese momento Abhay quiso unirse al Maṭh Gauḍīya como uno de los discípulos de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī. Pero ahora, en lugar de sus inclinaciones políticas, eran sus obligaciones familiares las que se interponían en el camino. Ya no pensaba: Primero, convirtámonos en una nación independiente, luego prediquemos sobre el Señor Caitanya. Ahora pensaba: No puedo participar como los demás. Tengo mis responsabilidades familiares.

|  | And the family was growing. In 1921 Abhay and his wife had had their first child, a son. And there would be more children, and more income would be needed. Earning money meant sacrificing time and energy, and it meant, at least externally, being distracted from the mission of Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī. Indian culture had the highest regard for the family institution, and divorce was unheard of. Even if a man was in great financial difficulty, he would remain with his wife and children. Although Abhay expressed regret at not being a sannyāsī disciple in the Gauḍīya Maṭh, he never seriously considered leaving his young wife so early in their marriage. Gour Mohan was pleased to hear of his son’s attraction to a Vaiṣṇava guru, but he never expected Abhay to abandon responsibilities and enter the renounced order. A Vaiṣṇava could remain with wife and family, practice spiritual life at home, and even become active in preaching. Abhay would have to find ways to serve the mission of Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī as a family man.

| | La familia estaba creciendo. En 1921, Abhay y su esposa tuvieron su primer hijo, un niño. Habría más hijos y se necesitarían más ingresos. Ganar dinero significaba sacrificar tiempo, energía y significaba, al menos externamente, distraerse de la misión de Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī. La cultura india tenía el mayor respeto por la institución familiar y el divorcio era inaudito. Incluso si un hombre tuviera grandes dificultades financieras, se quedaba con su esposa e hijos. Aunque Abhay expresó su pesar por no ser un discípulo sannyāsī en el Maṭh Gauḍīya, nunca consideró seriamente dejar a su joven esposa tan pronto en su matrimonio. Gour Mohan se alegró de escuchar la atracción de su hijo por un guru vaiṣṇava, pero nunca esperó que Abhay abandonara las responsabilidades y entrara en la orden de renuncia. Un vaiṣṇava podría permanecer con su esposa y su familia, practicar la vida espiritual en el hogar e incluso participar activamente en la predica. Abhay tendría que encontrar la forma de servir a la misión de Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī como hombre de familia.

|  | Abhay thought that if he were to become very successful in business, then he could spend money not only to support his family but also to help support Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī’s mission of spreading Kṛṣṇa consciousness. An astrologer had even predicted that Abhay would become one of the wealthiest men in India. But with his present income he could do little more than provide for his family’s needs. He thought he might do better by trying to develop a business on his own.

| | Abhay pensó que si tenía mucho éxito en los negocios, podría gastar dinero no solo para mantener a su familia sino también para ayudar a apoyar la misión de Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī de difundir la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa. Un astrólogo incluso predijo que Abhay se convertiría en uno de los hombres más ricos de la India. Pero con sus ingresos actuales, podría hacer poco más que satisfacer las necesidades de su familia. Pensó que podría mejorar intentando desarrollar un negocio por su cuenta.

|  | Abhay expressed his feelings to Dr. Bose, who listened like a sympathetic father and suggested that Abhay become his agent for all of northern India. Abhay could purchase medicines, liniments, rectified spirits, toothpastes, and other items wholesale from Dr. Bose’s factory and travel widely throughout northern India, building up his own business. Also, Abhay had enough experience with Bose’s Laboratory that he could try to make and market some of his own medicines and products. Dr. Bose and Abhay decided that the centrally located city of Allahabad would be a good place for Abhay to make his headquarters.

| | Abhay expresó sus sentimientos al Dr. Bose, quien escuchó como un padre comprensivo y sugirió que Abhay se convirtiera en su agente para todo el norte de la India. Abhay podía comprar medicinas, linimentos, licores rectificados, pastas dentales y otros artículos al por mayor en la fábrica del Dr. Bose y viajar ampliamente por el norte de la India, creando su propio negocio. Además, Abhay tenía la suficiente experiencia con el Laboratorio de Bose para intentar fabricar y comercializar algunos de sus propios medicamentos y productos. El Dr. Bose y Abhay decidieron que la ciudad céntrica de Allahabad sería un buen lugar para que Abhay hiciera su cuartel general.

|  | In 1923, Abhay and his wife and child moved to Allahabad, a twelve-hour train ride northwest from Calcutta. The British had once made Allahabad the capital of the United Provinces, and they had built many good buildings there, including buildings for a high court and a university. Europeans and affluent Indian families like the Nehrus lived in a modern, paved, well-lit section of town. There was also another, older section, with ancient narrow streets closely lined with buildings and shops. Many Bengalis resided there, and it was there that Abhay decided to settle his family.

| | En 1923, Abhay, su esposa e hijo se mudaron a Allahabad, un viaje en tren de doce horas al noroeste de Calcuta. Los británicos hicieron de Allahabad la capital de las Provincias Unidas y construyeron muchos buenos edificios allí, incluidos edificios para un tribunal superior y una universidad. Los europeos y las familias indias acomodadas como los Nehru vivían en una sección moderna, pavimentada y bien iluminada de la ciudad. También había otra sección más antigua, con calles estrechas bordeadas de edificios y tiendas. Muchos bengalíes residían allí, fue allí donde Abhay decidió establecer a su familia.

|  | He had chosen Allahabad, traditionally known as Prayāga, as a good location for business, but it was also one of India’s most famous places of pilgrimage. Situated at the confluence of the three holiest rivers of India – the Ganges, the Yamunā, and the Sarasvatī – Allahabad was the site of two of India’s most widely attended spiritual events, the annual Māgha-melā, and the Kumbha-melā, which took place every twelve years. And in search of spiritual purification, millions of pilgrims from all over India would converge here each year at the time of the full moon in the month of Māgha (January) and bathe at the junction of the three sacred rivers.

| | Eligió Allahabad, tradicionalmente conocido como Prayāga, como un buen lugar para los negocios, pero también era uno de los lugares de peregrinación más famosos de la India. Situado en la confluencia de los tres ríos más sagrados de la India: el Ganges, el Yamunā y el Sarasvatī, Allahabad fue el sitio de dos de los eventos espirituales más concurridos de la India, el Māgha-melā anual y el Kumbha-melā, que se realiza cada doce años. En busca de la purificación espiritual, millones de peregrinos de toda la India convergen allí cada año en el momento de la luna llena en el mes de Māgha (enero) y se bañan en la unión de los tres ríos sagrados.

|  | Abhay’s home at 60 Badshahi Mundi consisted of a few rented rooms. For his business he rented a small shop in the commercial center of the city at Johnston Gung Road, where he opened his dispensary, Prayag Pharmacy, and began selling medicines, tinctures, syrups, and other products manufactured by Bose’s Laboratory. He met an Allahabad physician, Dr. Ghosh, who was interested in a business partnership, so Abhay asked him to become his attending physician and move his office to Prayag Pharmacy. Dr. Ghosh consented and closed his own shop, Tropical Pharmacy.

| | La casa de Abhay en el 60 de la calle Badshahi Mundi consistía en unas pocas habitaciones alquiladas. Para su negocio, alquiló una pequeña tienda en el centro comercial de la ciudad en Johnston Gung Road, donde abrió su dispensario, Prayag Pharmacy y comenzó a vender medicamentos, tinturas, jarabes y otros productos fabricados por el Laboratorio Bose. Conoció a un médico de Allahabad, el Dr. Ghosh, que estaba interesado en una asociación comercial, por lo que Abhay le pidió que se convirtiera en su médico de cabecera y que trasladara su consultorio a Prayag Pharmacy. El Dr. Ghosh consintió y cerró su propia tienda, Tropical Pharmacy.

|  | At Prayag Pharmacy, Dr. Ghosh would diagnose patients and give medical prescriptions, which Abhay would fill. Dr. Ghosh would then receive a twenty-five-percent commission from the sale of the prescriptions. Abhay and Dr. Ghosh became friends; they would visit at each other’s home, and they treated each other’s children like their own family members. Often they discussed their aspirations for increasing profits.

| | En Prayag Pharmacy, el Dr. Ghosh diagnosticaba a los pacientes y les daba recetas médicas, que Abhay surtiría. El Dr. Ghosh recibía una comisión del veinticinco por ciento por la venta de las recetas. Abhay y el Dr. Ghosh se hicieron amigos; se visitaban en la casa del otro y trataban a los niños como a sus propios familiares. A menudo hablaban de sus aspiraciones de aumentar las ganancias.

|  | Dr. Ghosh: Abhay was a business-minded man. We were all God-fearing, of course. In every home we have a small temple, and we must have Deities. But he used to always talk about business and how to meet family expenses.

| | Dr. Ghosh: Abhay era un hombre de negocios. Todos temíamos a Dios, por supuesto. En cada hogar teníamos un pequeño templo, con deidades. Pero solía hablar siempre de negocios y cómo cubrir los gastos familiares.

|  | Although at home Abhay wore a kurtā and dhotī, sometimes for business he would dress in shirt and pants. He was a good-looking, full-mustached, energetic young man in his late twenties. He and Radharani De now had two children – a daughter was born after they had been in Allahabad one year. Gour Mohan, who was now seventy-five, had come to live with him, as had Abhay’s widowed sister, Rajesvari, and her son, Tulasi. Gour Mohan mostly stayed at home, chanted on his beads, and worshiped the śālagrāma-śilā Deity of Kṛṣṇa. He was satisfied that Abhay was doing right, and Abhay was satisfied to have his father living comfortably with him and freely worshiping Kṛṣṇa.

| | Aunque en casa Abhay usaba kurtā y dhotī, en ocasiones se vestía con camisa y pantalones por negocios. Era un joven apuesto, bigotudo y enérgico de unos treinta años. Él y Radharani De ahora tenían dos hijos: una hija nació después de estar un año en Allahabad. Gour Mohan, que ahora tenía setenta y cinco años, fue a vivir con él, al igual que la hermana viuda de Abhay, Rajesvari y su hijo, Tulasi. Gour Mohan se quedó principalmente en casa, cantaba sus cuentas y adoraba a la Deidad śālagrāma-śilā de Kṛṣṇa. Estaba satisfecho de que Abhay estaba haciendo lo correcto y Abhay estaba satisfecho de tener a su padre viviendo cómodamente con él y adorando pacíficamente a Kṛṣṇa.

|  | Abhay led a busy life. He was intent on building his business. By 8:00 A.M. he would go to his pharmacy, where he would meet Dr. Ghosh and begin his day’s work. At noon he would come home, and then he would return to the pharmacy in the late afternoon. He had purchased a large Buick for eight thousand rupees, and although he never drove it himself, he let his nephew, a good driver, use it for his taxi business. Occasionally, Abhay would use the car on his own business excursions, and his nephew would then act as his chauffeur.

| | Abhay llevó una vida ocupada. Tenía la intención de incrementar su negocio. A las 8:00 a.m. iba a su farmacia, donde se encontraba con el Dr. Ghosh y comenzaba su día de trabajo. Al mediodía volvía a casa y luego regresaría a la farmacia al final de la tarde. Había comprado un Buick grande por ocho mil rupias, y aunque nunca lo condujo él mismo, dejó que su sobrino, un buen conductor, lo usara para su negocio de taxis. Ocasionalmente, Abhay usaba el automóvil en sus propias excursiones de negocios y su sobrino actuaba como su chofer.

|  | It so happened that both Motilal Nehru and his son Jawaharlal were customers at Prayag Pharmacy. Because Jawaharlal would always order Western medicines, Abhay thought he must have felt that Indian ways were inferior. Once, Jawaharlal approached Abhay for a political contribution, and Abhay donated, being a conscientious merchant. During the day Abhay would talk with his customers and other friends who would stop by, and they would tell him many things. A former military officer used to tell Abhay stories of World War I. He told how Marshal Foch in France had one day ordered the killing of thousands of Belgian refugees whose maintenance had become a burden to him on the battlefield. A Muhammadan gentleman, a member of a royal family in Afghanistan, would come daily with his son to sit and chat. Abhay would listen to his visitors and converse pleasantly and make up their prescriptions, but his thoughts kept returning to his meeting with Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī. He went over it again and again in his mind – how he had looked, his mannerisms, what he had said.

| | Dio la casualidad de que tanto Motilal Nehru como su hijo Jawaharlal eran clientes de la farmacia Prayag. Como Jawaharlal siempre pediría medicinas occidentales, Abhay pensó que debía haber sentido que las costumbres indias eran inferiores. Una vez, Jawaharlal se acercó a Abhay para una contribución política y Abhay donó, siendo un comerciante concienzudo. Durante el día, Abhay hablaba con sus clientes y otros amigos que se detenían y le contaban muchas cosas. Un ex oficial militar solía contarle a Abhay historias de la Primera Guerra Mundial. Contó cómo el mariscal Foch en Francia ordenó un día la muerte de miles de refugiados belgas cuyo mantenimiento se había convertido en una carga para él en el campo de batalla. Un caballero de Mahoma, miembro de una familia real en Afganistán, venía diariamente con su hijo a sentarse y conversar. Abhay escuchaba a sus visitantes y conversaba agradablemente y preparaba sus recetas, pero sus pensamientos seguían volviendo a su reunión con Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī. La repasó una y otra vez en su mente: cómo se veía, sus modales y lo que dijo.

|  | At night Abhay would go home to his wife and children. Radharani was a chaste and faithful wife who spent her days cooking, cleaning, and caring for her two children. But she was not inclined to share her husband’s interest in things spiritual. He could not convey to her his feelings about Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī.

| | Por la noche, Abhay iba a casa con su esposa e hijos. Radharani fue una esposa casta y fiel que pasaba sus días cocinando, limpiando y cuidando a sus dos hijos. Pero no estaba dispuesta a compartir el interés de su esposo con las cosas espirituales. No podía transmitirle sus sentimientos sobre Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī.

|  | Abhay; his wife; their two children; Gour Mohan; Abhay’s younger brother, Kṛṣṇa Charan; Abhay’s widowed sister, Rajesvari; and her son, Tulasi das, all went together to an Allahabad studio for a family portrait. The photo shows Abhay in his late twenties. He is thin and dark, with a full mustache. His forehead is broad, his eyes dark and clear. He wears a white kurtā and dhotī and plain dark slippers. He sits in a chair, his wife standing behind him, an attractive young woman in a white khādī sārī with a line of color on the border. Her slim arm rests behind Abhay’s head on the back of his chair, her small hand gripping the edge of the chair. Her left hand hangs by her side, gripped in a fist. She is barefoot. With his left hand, Abhay steadies his two-year-old boy, “Pacha” (Prayag Raj), a glaring infant, on his lap, the boy seeming to squirm, his baby legs and bare feet dangling by his mother’s knee. Abhay seems a bit amused by the son on his lap. Abhay is a handsome Indian man, his wife an attractive woman, both young.

| | Abhay, su esposa; sus dos hijos; Gour Mohan el hermano menor de Abhay, Kṛṣṇa Charan; la hermana viuda de Abhay, Rajesvari; y su hijo, Tulasi das, todos fueron juntos a un estudio de Allahabad para un retrato familiar. La foto muestra a Abhay en sus veintes. Es delgado y moreno, con un bigote completo. Su frente es amplia, sus ojos obscuros y claros. Lleva una kurtā blanca y dhotī, zapatillas oscuras. Se sienta en una silla, con su esposa parada detrás de él, una joven atractiva con un khādī sārī blanco con una línea de color en el borde. Su brazo delgado descansa detrás de la cabeza de Abhay en el respaldo de su silla, su pequeña mano agarrando el borde de la silla. Su mano izquierda cuelga a su lado, apretada en un puño. Ella esta descalza. Con su mano izquierda, Abhay aquieta a su niño de dos años, “Pacha” (Prayag Raj), un niño deslumbrante, en su regazo, el niño parece retorcerse, sus piernas de bebé y los pies descalzos colgando de la rodilla de su madre. Abhay parece algo alegre por su hijo en su regazo. Abhay es un apuesto hombre indio, su esposa es una mujer atractiva, ambos jóvenes.

|  | Also behind Abhay stands his nephew Tulasi and his brother, Kṛṣṇa Charan. Sitting on the far right is Abhay’s sister Rajesvari, dressed in a widow’s white sārī, holding Sulakshmana, Abhay’s daughter, on her lap. Sulakshmana is also squirming, her foot jutting towards the photographer. In the center sits Gour Mohan. His face is shriveled, and his whole body is emaciated with age. He is also wearing a white kurtā and dhotī. His hands seem to be moving actively on his lap, perhaps with palsy. He is short and small and old.

| | También detrás de Abhay se encuentra su sobrino Tulasi y su hermano, Kṛṣṇa Charan. Sentada en el extremo derecho está Rajesvari, la hermana de Abhay, vestida con un sārī blanco de viuda, sosteniendo a Sulakshmana, la hija de Abhay, en su regazo. Sulakshmana también se retuerce, su pie sobresale hacia el fotógrafo. En el centro se encuentra Gour Mohan. Su cara está arrugada y todo su cuerpo está demacrado por la edad. También lleva una kurtā blanca y un dhotī. Sus manos parecen moverse activamente en su regazo, quizás con parálisis. Es bajo, pequeño y viejo.

|  | Abhay traveled frequently throughout northern India, intent on expanding his sales. It was not unusual for him to be gone a few days in a week, and sometimes a week or more at a time, as he traveled from one city to another. The pharmaceutical industry was just beginning in India, and doctors, hospitals, and pharmacies were eager to buy from the competent, gentlemanly agent who called on them from Bose’s Laboratory of Calcutta.

| | Abhay viajaba frecuentemente por el norte de la India, con la intención de expandir sus ventas. No era inusual que se fuera unos días a la semana, a veces una semana o más a la vez, mientras viajaba de una ciudad a otra. La industria farmacéutica apenas comenzaba en la India y los médicos, hospitales y farmacias estaban ansiosos por comprarle al agente competente y caballeroso que los visitó del Laboratorio de Bose de Calcuta.

|  | He would travel by train and stay in hotels. He liked the feeling of freedom from home that traveling afforded, but the real drive was servicing accounts and getting new ones; that was his business. Riding in a third-class unreserved compartment was often uncomfortable; the only seats were benches, which were often dirty, and passengers were permitted to crowd on without reservations. But that is how Abhay traveled, hundreds of miles every week. As the train moved between towns, he would see the numberless small villages and then the country land that spread out before him on either side of the tracks. At every stop, he would hear the cries of the tea vendors as they walked alongside the train windows: “Chāy! Chāy!” Tea! The British had introduced it, and now millions of Indians were convinced that they could not get through the morning without their little glass of hot tea. As a strict Vaiṣṇava, Abhay never touched it, but his wife, much to his displeasure, was becoming a regular tea drinker.

| | Viajaba en tren y se alojaba en hoteles. Le gustaba la sensación de libertad del hogar que le permitía viajar, pero el verdadero impulso era atender las cuentas y obtener otras nuevas; ese era su negocio. Viajar en un compartimento no reservado de tercera clase a menudo era incómodo; los únicos asientos eran bancas, que a menudo estaban sucias y se permitía a los pasajeros abarrotarse sin reservas. Pero así es como Abhay viajaba, cientos de kilómetros cada semana. A medida que el tren se movía entre las ciudades, veía las innumerables aldeas pequeñas y luego la tierra del campo que se extendía ante él a ambos lados de las vías. En cada parada, escuchaba los gritos de los vendedores de té mientras caminaban junto a las ventanas del tren: “¡Chāy! ¡Chāy! ¡Té! Los británicos lo introdujeron y ahora millones de indios estaban convencidos de que no podían pasar la mañana sin su pequeño vaso de té caliente. Como un estricto vaiṣṇava, Abhay nunca lo tocó, pero su esposa, para su disgusto, se estaba convirtiendo en una bebedora de té.

|  | Although Abhay was accustomed to dressing as a European businessman, he never compromised his strict Vaiṣṇava principles. Most of his fellow Bengalis had taken up fish-eating, but Abhay was always careful to avoid non-Vaiṣṇava foods, even at hotels. Once at a vegetarian hotel, the Empire Hindu Hotel in Bombay, he was served onions, and sometimes hotel people tried to serve him mushrooms, garlic, and even eggs, but all of these he carefully avoided. Keeping a small semblance of his home routine, he would take his bath early in the morning with cold water. He followed this routine year-round, and when, in Saharanpur, he did so during the bitter cold weather, the hotelkeeper was greatly surprised.