|

Śrīla Prabhupāda Līlambṛta - — Śrīla Prabhupāda Līlambṛta

Volume 3 — Only He Could Lead Them — Volumen 3 — Solo él podía guiarlos

<< 22 Swami Invites the Hippies >> — << 22 Swamiji invita a los hippies >>

| January 16, 1967

| | 16 de enero de 1967

|  | AS THE UNITED Airlines jet descended on the San Francisco Bay area, Śrīla Prabhupāda turned to his disciple Ranchor and said, “The buildings look like matchboxes. Just imagine how it looks from Kṛṣṇa’s viewpoint.”

| | MIENTRAS EL AVIÓN de United Airlines descendía sobre el área de la Bahía de San Francisco, Śrīla Prabhupāda se volvió hacia su discípulo Ranchor y dijo: “Los edificios parecen cajas de cerillas. Imagína cómo se ven desde el punto de vista de Kṛṣṇa. “.

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda was seventy-one years old, and this had been his first air trip. Ranchor, nineteen and dressed in a suit and tie, was supposed to be Śrīla Prabhupāda’s secretary. He was a new disciple but had raised some money and had asked to fly to San Francisco with Prabhupāda.

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda tenía setenta y un años y este fue su primer viaje aéreo. Se suponía que Ranchor, de diecinueve años y vestido con traje y corbata, era el secretario de Śrīla Prabhupāda. Era un discípulo nuevo pero había recaudado algo de dinero y pudo volar a San Francisco con Prabhupāda.

|  | During the trip Śrīla Prabhupāda had spoken little. He had been chanting: “Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa, Hare Hare / Hare Rāma, Hare Rāma, Rāma Rāma, Hare Hare.” His right hand in his cloth bead bag, he had been fingering one bead after another as he chanted silently to himself. When the plane had first risen over New York City, he had looked out the window at the buildings growing smaller and smaller. Then the plane had entered the clouds, which to Prabhupāda had appeared like an ocean in the sky. He had been bothered by pressure blocking his ears and had mentioned it; otherwise he hadn’t said much, but had only chanted Kṛṣṇa’s names over and over. Now, as the plane began its descent, he continued to chant, his voice slightly audible – “Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa …” – and he looked out the window at the vista of thousands of matchbox houses and streets stretching in charted patterns in every direction.

| | Durante el viaje, Śrīla Prabhupāda había habló poco. Estuvo cantando: “Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa, Hare Hare/ Hare Rāma, Hare Rāma, Rāma Rāma, Hare Hare". Con la mano derecha en su bolsa de tela con cuentas, estuvo tocando una cuenta tras otra mientras cantaba en silencio para sí mismo. Cuando el avión sobrevoló la ciudad de Nueva York por primera vez, miró por la ventana los edificios cada vez más pequeños. Entonces el avión entró en las nubes, que a Prabhupāda le habían parecido como un océano en el cielo. Le molestó la presión que le tapaba los oídos lo mencionó; de lo contrario, no habría dicho mucho, sino que solo cantó los nombres de Kṛṣṇa una y otra vez. Ahora, cuando el avión comenzó a descender, continuó cantando, su voz ligeramente audible -. “Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa ....” - y miró por la ventana a la vista de miles de casas de cerillas y calles que se extendían en patrones trazados en todas direcciones.

|  | When the announcement for United Airlines Flight 21 from New York came over the public-address system, the group of about fifty hippies gathered closer together in anticipation. For a moment they appeared almost apprehensive, unsure of what to expect or what the Svāmī would be like.

| | Cuando el anuncio del vuelo 21 de United Airlines desde Nueva York llegó a través del sistema de megafonía, el grupo de unos cincuenta hippies se reunió más cerca con anticipación. Por un momento parecieron casi aprensivos, inseguros de qué esperar o cómo sería el Svāmī.

|  | Roger Segal: We were quite an assorted lot, even for the San Francisco airport. Mukunda was wearing a Merlin the Magician robe with paisley squares all around, Sam was wearing a Moroccan sheep robe with a hood – he even smelled like a sheep – and I was wearing a sort of blue homemade Japanese samurai robe with small white dots. Long strings of beads were everywhere. Buckskins, boots, army fatigues, people wearing small, round sunglasses – the whole phantasmagoria of San Francisco at its height.

| | Roger Segal: Éramos un grupo bastante variado, incluso para el aeropuerto de San Francisco. Mukunda vestía una túnica de Merlín el Mago con cuadros de cachemira alrededor, Sam vestía una túnica de oveja marroquí con capucha, incluso olía a oveja, y yo llevaba una especie de túnica de samurái japonesa hecha en casa azul con pequeños puntos blancos. Había largas hileras de cuentas por todas partes. Buckskins, botas, uniformes militares, gente con gafas de sol pequeñas y redondas: toda la fantasmagoría de San Francisco en su apogeo.

|  | Only a few people in the crowd knew Svāmīji: Mukunda and his wife, Jānakī; Ravīndra-svarūpa; Rāya Rāma – all from New York. And Allen Ginsberg was there. (A few days before, Allen had been one of the leaders of the Human Be-In in Golden Gate Park, where over two hundred thousand had come together – “A Gathering of the Tribes … for a joyful pow-wow and Peace Dance.”) Today Allen was on hand to greet Svāmī Bhaktivedanta, whom he had met and chanted with several months before on New York’s Lower East Side.

| | Solo unas pocas personas de la multitud conocían a Svāmīji: Mukunda y su esposa, Jānakī; Ravīndra-svarūpa; Rāya Rāma: todos de Nueva York. Allen Ginsberg estaba allí. (Unos días antes, Allen fue uno de los líderes del Human Be-In en el Parque Golden Gate, donde más de doscientos mil se habían reunido - “Una Reunión de las Tribus ... para un alegre pow-wow y Baile de la Paz.”) Hoy Allen estaba presente para saludar a Svāmī Bhaktivedanta, a quien conocía y con quien cantó varios meses antes en el Lado Este Bajo de Nueva York.

|  | Svāmīji would be pleased, Mukunda reminded everyone, if they were all chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa when he came through the gate. They were already familiar with the Hare Kṛṣṇa mantra. They had heard about the Svāmī’s chanting in the park in New York or they had seen the article about Svāmīji and the chanting in the local underground paper, The Oracle. Earlier today they had gathered in Golden Gate Park – most of them responding to a flyer Mukunda had distributed – and had chanted there for more than an hour before coming to the airport in a caravan of cars. Now many of them – also in response to Mukunda’s flyer – stood with incense and flowers in their hands.

| | Mukunda les recordó a todos que Svāmīji estaría complacido si todos estaban cantando Hare Kṛṣṇa cuando él cruzara la puerta. Ya estaban familiarizados con el mantra Hare Kṛṣṇa. Habían oído hablar del canto de Svāmī en el parque de Nueva York o habían visto el artículo sobre Svāmīji y el canto en el periódico clandestino local, The Oracle. Hoy temprano se habían reunido en el Parque Golden Gate, la mayoría respondiendo a un volante que Mukunda distribuyó, y habían coreado allí durante más de una hora antes de llegar al aeropuerto en una caravana de autos. Ahora, muchos de ellos, también en respuesta al volante de Mukunda, estaban de pie con incienso y flores en la mano.

|  | As the disembarking passengers entered the terminal gate and walked up the ramp, they looked in amazement at the reception party of flower-bearing chanters. The chanters, however, gazed past these ordinary, tired-looking travelers, searching for that special person who was supposed to be on the plane. Suddenly, strolling toward them was the Svāmī, golden-complexioned, dressed in bright saffron robes.

| | Cuando los pasajeros que desembarcaban entraron por la puerta de la terminal y subieron por la rampa, miraron con asombro la fiesta de recepción de cantantes con flores. Los cantantes, sin embargo, miraron más allá de estos viajeros ordinarios y de aspecto cansado, en busca de esa persona especial que se suponía que estaba en el avión. De repente, caminando hacia ellos estaba el Svāmī, de tez dorada, vestido con una túnica color azafrán brillante.

|  | Prabhupāda had heard the chanting even before he had entered the terminal, and he had begun to smile. He was happy and surprised. Glancing over the faces, he recognized only a few. Yet here were fifty people receiving him and chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa without his having said a word!

| | Prabhupāda había escuchado el cántico incluso antes de entrar en la terminal y comenzó a sonreír. Estaba feliz y sorprendido. Echando un vistazo a los rostros, reconoció solo algunos. ¡Sin embargo, había cincuenta personas recibiéndolo y cantando Hare Kṛṣṇa sin que él hubiera dicho una palabra!

|  | Mukunda: We just had a look at Svāmīji, and then we bowed down – myself, my wife, and the friends I had brought, Sam and Marjorie. And then all of the young men and women there followed suit and all bowed down to Svāmīji, just feeling very confident that it was the right and proper thing to do.

| | Mukunda: Acabamos de echar un vistazo a Svāmīji, luego nos inclinamos: yo, mi esposa y los amigos que había traído, Sam y Marjorie. Entonces todos los hombres y mujeres jóvenes hicieron lo mismo y se inclinaron ante Svāmīji, sintiéndose muy seguros de que era lo propio y correcto del momento.

|  | The crowd of hippies had formed a line on either side of a narrow passage through which Svāmīji would walk. As he passed among his new admirers, dozens of hands stretched out to offer him flowers and incense. He smiled, collecting the offerings in his hands while Ranchor looked on. Allen Ginsberg stepped forward with a large bouquet of flowers, and Śrīla Prabhupāda graciously accepted it. Then Prabhupāda began offering the gifts back to all who reached out to receive them. He proceeded through the terminal, the crowd of young people walking beside him, chanting.

| | La multitud de hippies formó una línea a ambos lados de un estrecho pasaje por el que Svāmīji caminaría. Al pasar entre sus nuevos admiradores, decenas de manos se extendieron para ofrecerle flores e incienso. Sonrió, recogiendo las ofrendas en sus manos mientras Ranchor miraba. Allen Ginsberg dio un paso adelante con un gran ramo de flores y Śrīla Prabhupāda lo aceptó amablemente. Entonces Prabhupāda comenzó a ofrecer los regalos a todos los que se acercaran para recibirlos. Pasó por la terminal, la multitud de jóvenes caminaba a su lado, cantando.

|  | At the baggage claim Śrīla Prabhupāda waited for a moment, his eyes taking in everyone around him. Lifting his open palms, he beckoned everyone to chant louder, and the group burst into renewed chanting, with Prabhupāda standing in their midst, softly clapping his hands and singing Hare Kṛṣṇa. Gracefully, he then raised his arms above his head and began to dance, stepping and swaying from side to side.

| | En la zona de recogida de equipajes, Śrīla Prabhupāda esperó un momento, con la mirada fija en todos los que le rodeaban. Levantando sus palmas abiertas, hizo señas a todos para que cantaran más fuerte, el grupo estalló en cánticos renovados, con Prabhupāda de pie en medio de ellos, aplaudiendo suavemente y cantando Hare Kṛṣṇa. Con gracia, luego levantó los brazos por encima de la cabeza y comenzó a bailar, dando pasos y balanceándose de un lado a otro.

|  | To the mixed chagrin, amusement, and irresistible joy of the airport workers and passengers, the reception party stayed with Prabhupāda until he got his luggage. Then they escorted him outside into the sunlight and into a waiting car, a black 1949 Cadillac Fleetwood. Prabhupāda got into the back seat with Mukunda and Allen Ginsberg. Until the moment the car pulled away from the curb, Śrīla Prabhupāda, still smiling, continued handing flowers to all those who had come to welcome him as he brought Kṛṣṇa consciousness west.

| | Para disgusto, diversión y alegría irresistible de los trabajadores del aeropuerto y los pasajeros, la fiesta de la recepción se quedó con Prabhupāda hasta que recibió su equipaje. Luego lo escoltaron afuera hacia la luz del sol y dentro de un automóvil que esperaba, un Cadillac Fleetwood negro de 1949. Prabhupāda se sentó en el asiento trasero con Mukunda y Allen Ginsberg. Hasta el momento en que el automóvil se apartó de la acera, Śrīla Prabhupāda, todavía sonriendo, continuó entregando flores a todos los que habían venido a darle la bienvenida mientras llevaba la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa al oeste.

|  | The Cadillac belonged to Harvey Cohen, who almost a year before had allowed Prabhupāda to stay in his Bowery loft. Harvey was driving, but because of his chauffeur’s hat (picked up at a Salvation Army store) and his black suit and his beard, Prabhupāda didn’t recognize him.

| | El Cadillac pertenecía a Harvey Cohen, quien casi un año antes había permitido que Prabhupāda se quedara en su ático de Bowery. Harvey conducía, pero debido a su sombrero de chófer (recogido en una tienda del Ejército de Salvación), su traje negro y su barba, Prabhupāda no lo reconoció.

|  | “Where is Harvey?” Prabhupāda asked.

“He’s driving,” Mukunda said.

“Oh, is that you? I didn’t recognize you.”

Harvey smiled. “Welcome to San Francisco, Svāmīji.”

| | "¿Dónde está Harvey?.” Preguntó Prabhupāda.

"Está conduciendo", dijo Mukunda.

“Oh, ¿eres tú? No te reconocí. “.

Harvey sonrió. “Bienvenido a San Francisco, Svāmīji".

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda was happy to be in another big Western city on behalf of his spiritual master, Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, and Lord Caitanya. The further west one goes, Lord Caitanya had said, the more materialistic the people. Yet, Lord Caitanya had also said that Kṛṣṇa consciousness should spread all over the world. Prabhupāda’s Godbrothers had often wondered about Lord Caitanya’s statement that one day the name of Kṛṣṇa would be sung in every town and village. Perhaps that verse should be taken symbolically, they said; otherwise, what could it mean – Kṛṣṇa in every town? But Śrīla Prabhupāda had deep faith in that statement by Lord Caitanya and in the instruction of his spiritual master. Here he was in the far-Western city of San Francisco, and already people were chanting. They had enthusiastically received him with flowers and kīrtana. And all over the world there were other cities much like this one.

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda estaba feliz de estar en otra gran ciudad occidental en nombre de su maestro espiritual, Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī y del Señor Caitanya. Cuanto más al oeste uno va, había dicho el Señor Caitanya, más materialista es la gente. Sin embargo, el Señor Caitanya también dijo que la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa debería extenderse por todo el mundo. Los hermanos espirituales de Prabhupāda se habían preguntado a menudo acerca de la declaración del Señor Caitanya de que un día se cantaría el nombre de Kṛṣṇa en todos los pueblos y aldeas. Quizás ese verso debería tomarse simbólicamente, dijeron; de lo contrario, ¿qué podría significar: Kṛṣṇa en cada pueblo? Pero Śrīla Prabhupāda tenía una fe profunda en esa declaración del Señor Caitanya y en la instrucción de su maestro espiritual. Aquí estaba en la ciudad de San Francisco, en el lejano oeste y ya la gente cantaba. Lo habían recibido con entusiasmo con flores y kīrtana. Y en todo el mundo habría otras ciudades muy parecidas a esta.

|  | The temple Mukunda and his friends had obtained was on Frederick Street in the Haight-Ashbury district. Like the temple at 26 Second Avenue in New York, it was a small storefront with a display window facing the street. A sign over the window read, SRI SRI RADHA KRISHNA TEMPLE. Mukunda and his friends had also rented a three-room apartment for Svāmīji on the third floor of the adjoining building. It was a small, bare, run-down apartment facing the street.

| | El templo que Mukunda y sus amigos habían obtenido estaba en la Calle Frederick en el distrito de Haight-Ashbury. Al igual que el templo del número 26 de la Segunda Avenida de Nueva York, era un pequeño local con un escaparate que daba a la calle. Un letrero sobre la ventana decía: TEMPLO DE SRI SRI RADHA KRISHNA. Mukunda y sus amigos también habían alquilado un apartamento de tres habitaciones para Svāmīji en el tercer piso del edificio contiguo. Era un apartamento pequeño, vacío y en ruinas que daba a la calle.

|  | Followed by several carloads of devotees and curious seekers, Śrīla Prabhupāda arrived at 518 Frederick Street and entered the storefront, which was decorated only by a few madras cloths on the wall. Taking his seat on a cushion, he led a kīrtana and then spoke, inviting everyone to take up Kṛṣṇa consciousness. After his lecture he left the storefront and walked next door and up the two flights of stairs to his apartment. As he entered his apartment, number 32, he was followed not only by his devotees and admirers but also by reporters from San Francisco’s main newspapers: the Chronicle and the Examiner. While some devotees cooked his lunch and Ranchor unpacked his suitcase, Svāmīji talked with the reporters, who sat on the floor, taking notes on their pads.

| | Seguido por varios carros llenos de devotos y buscadores curiosos, Śrīla Prabhupāda llegó al 518 de la Calle Frederick y entró en la tienda que estaba decorada solo con algunas telas de madrás en la pared. Se sentó en un cojín, dirigió un kīrtana y luego habló, invitando a todos a tomar la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa. Después de su conferencia, salió de la tienda, caminó por la puerta de al lado y subió los dos tramos de escaleras hasta su apartamento. Al entrar en su apartamento, el número 32, fue seguido no sólo por sus devotos y admiradores, sino también por los reporteros de los principales periódicos de San Francisco: el Chronicle y el Examiner. Mientras algunos devotos cocinaban su almuerzo y Ranchor desempacaba su maleta, Svāmīji hablaba con los reporteros, quienes estaban sentados en el piso y tomando notas en sus libretas.

|  | Reporter: “Downstairs, you said you were inviting everyone to Kṛṣṇa consciousness. Does that include the Haight-Ashbury Bohemians and beatniks?”

| | Periodista: “Abajo, dijo que estaba invitando a todos a la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa. ¿Eso incluye a los bohemios y beatniks de Haight-Ashbury?

|  | Prabhupāda: “Yes, everyone, including you or anybody else, be he or she what is called an ‘acidhead’ or a hippie or something else. But once he is accepted for training, he becomes something else from what he had been before.”

| | Prabhupāda: “Sí, todo el mundo, incluido usted o cualquier otra persona, sea él o ella lo que se llama un 'cabeza ácida' o un hippie o algo más. Pero una vez que es aceptado para el entrenamiento, se convierte en algo diferente de lo que había sido antes".

|  | Reporter: “What does one have to do to become a member of your movement?”

| | Periodista:. “¿Qué tiene que hacer uno para convertirse en miembro de su movimiento?"

|  | Prabhupāda: “There are four prerequisites. I do not allow my students to keep girlfriends. I prohibit all kinds of intoxicants, including coffee, tea and cigarettes. I prohibit meat-eating. And I prohibit my students from taking part in gambling.”

| | Prabhupāda: “Hay cuatro requisitos previos. No permito que mis alumnos se queden con novias. Prohíbo todo tipo de intoxicantes, incluidos el café, el té y los cigarrillos. Prohíbo comer carne. Y prohíbo a mis estudiantes participar en juegos de azar".

|  | Reporter: “Do these shall-not commandments extend to the use of LSD, marijuana, and other narcotics?”

| | Periodista:. “¿Estos mandamientos no se extienden al uso de LSD, marihuana y otros narcóticos?"

|  | Prabhupāda: “I consider LSD to be an intoxicant. I do not allow any one of my students to use that or any intoxicant. I train my students to rise early in the morning, to take a bath early in the day, and to attend prayer meetings three times a day. Our sect is one of austerity. It is the science of God.”

| | Prabhupāda: “Considero que el LSD es un intoxicante. No permito que ninguno de mis estudiantes use ese o cualquier otro intoxicante. Enseño a mis alumnos a levantarse temprano en la mañana, a bañarse temprano en el día y a asistir a las reuniones de oración tres veces al día. Nuestro grupo es de austeridad. Es la ciencia de Dios”.

|  | Although Prabhupāda had found that reporters generally did not report his philosophy, he took the opportunity to preach Kṛṣṇa consciousness. Even if the reporters didn’t want to delve into the philosophy, his followers did. “The big mistake of modern civilization,” Śrīla Prabhupāda continued, “is to encroach upon others’ property as though it were one’s own. This creates an unnatural disturbance. God is the ultimate proprietor of everything in the universe. When people know that God is the ultimate proprietor, the best friend of all living entities, and the object of all offerings and sacrifices – then there will be peace.”

| | Aunque Prabhupāda había descubierto que los periodistas generalmente no informaban sobre su filosofía, aprovechó la oportunidad para predicar el proceso de Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa. Incluso si los reporteros no quisieron ahondar en la filosofía, sus seguidores sí lo hicieron. “El gran error de la civilización moderna”, continuó Śrīla Prabhupāda, “es invadir la propiedad de otros como si fuera la propia. Esto crea una perturbación antinatural. Dios es el propietario final de todo en el universo. Cuando la gente sepa que Dios es el propietario máximo, el mejor amigo de todas las entidades vivientes y el objeto de todas las ofrendas y sacrificios, entonces habrá paz".

|  | The reporters asked him about his background, and he told briefly about his coming from India and beginning in New York.

| | Los reporteros le preguntaron acerca de sus antecedentes y él les contó brevemente sobre su llegada de la India y su comienzo en Nueva York.

|  | After the reporters left, Prabhupāda continued speaking to the young people in his room. Mukunda, who had allowed his hair and beard to grow but who wore around his neck the strand of large red beads Svāmīji had given him at initiation, introduced some of his friends and explained that they were all living together and that they wanted to help Svāmīji present Kṛṣṇa consciousness to the young people of San Francisco. Mukunda’s wife, Jānakī, asked Svāmīji about his plane ride. He said it had been pleasant except for some pressure in his ears. “The houses looked like matchboxes,” he said, and with his thumb and forefinger he indicated the size of a matchbox.

| | Después de que los reporteros se fueron, Prabhupāda continuó hablando con los jóvenes en su habitación. Mukunda, que se había dejado crecer el pelo y la barba, pero que llevaba alrededor del cuello el hilo de grandes cuentas rojas que Svāmīji le había dado en la iniciación, presentó a algunos de sus amigos y les explicó que todos vivían juntos y que querían ayudar a Svāmīji. presente la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa a los jóvenes de San Francisco. La esposa de Mukunda, Jānakī, le preguntó a Svāmīji sobre su viaje en avión. Dijo que había sido agradable excepto por un poco de presión en los oídos. “Las casas parecían cajas de cerillas”, dijo, y con el pulgar y el índice indicó el tamaño de una caja de cerillas.

|  | He leaned back against the wall and took off the garlands he had received that day, until only a beaded necklace – a common, inexpensive item with a small bell on it – remained hanging around his neck. Prabhupāda held it, inspected the workmanship, and toyed with it. “This is special,” he said, looking up, “because it was made with devotion.” He continued to pay attention to the necklace, as if receiving it had been one of the most important events of the day.

| | Se reccargó contra la pared y se quitó las guirnaldas que había recibido ese día, hasta dejar solo un collar de cuentas, un artículo común y económico con una pequeña campana, quedó colgando de su cuello. Prabhupāda lo sostuvo, inspeccionó la mano de obra y jugó con él. “Esto es especial", dijo, mirando hacia arriba,. “porque fue hecho con devoción". Continuó prestando atención al collar, como si recibirlo hubiera sido uno de los eventos más importantes del día.

|  | When his lunch arrived, he distributed some to everyone, and then Ranchor efficiently though tactlessly asked everyone to leave and give the Svāmī a little time to eat and rest.

| | Cuando llegó su almuerzo, distribuyó un poco a todos, luego Ranchor, eficientemente, aunque sin tacto, pidió a todos que se fueran y le dieran al Svāmī un poco de tiempo para comer y descansar.

|  | Outside the apartment and in the storefront below, the talk was of Svāmīji. No one had been disappointed. Everything Mukunda had been telling them about him was true. They particularly enjoyed how he had talked about seeing everything from Kṛṣṇa’s viewpoint.

| | Fuera del apartamento y en el local de abajo, se hablaba de Svāmīji. Nadie se había decepcionado. Todo lo que Mukunda les había estado diciendo sobre él era cierto. Disfrutaron especialmente de cómo les había hablado de ver todo desde el punto de vista de Kṛṣṇa.

|  | That night on television Svāmīji’s arrival was covered on the eleven o’clock news, and the next day it appeared in the newspapers. The Examiner’s story was on page two – “Svāmī Invites the Hippies” – along with a photo of the temple, filled with followers, and some shots of Svāmīji, who looked very grave. Prabhupāda had Mukunda read the article aloud.

| | Esa noche, en la televisión, la llegada de Svāmīji fue cubierta en las noticias de las once y al día siguiente apareció en los periódicos. La historia de The Examiner estaba en la página dos,. “Svāmī invita a los hippies", junto con una foto del templo, lleno de seguidores y algunas fotos de Svāmīji, que parecía muy serio. Prabhupāda hizo que Mukunda leyera el artículo en voz alta.

|  | “The lanky ‘Master of the Faith,’ ” Mukunda read, “attired in a flowing ankle-long robe and sitting cross-legged on a big mattress – ”

| | "El larguirucho 'Maestro de la Fe'", leyó Mukunda,. “vestido con una túnica suelta hasta los tobillos y sentado con las piernas cruzadas sobre un gran colchón..."

|  | Svāmīji interrupted, “What is this word lanky?”

| | Svāmīji interrumpió,. “¿Qué es esta palabra larguirucho?"

|  | Mukunda explained that it meant tall and slender. “I don’t know why they said that,” he added. “Maybe it’s because you sit so straight and tall, so they think that you are very tall.” The article went on to describe many of the airport greeters as being “of the long-haired, bearded and sandaled set.”

| | Mukunda explicó, que significa alto y delgado. “No sé por qué dijeron eso", agregó. “Tal vez sea porque te sientas muy erguido y alto, entonces ellos piensan que eres muy alto". El artículo continuó describiendo a muchos de los asistentes al aeropuerto como. “del grupo de pelo largo, barbudo y sandalias".

|  | San Francisco’s largest paper, the Chronicle, also ran an article: “Svāmī in Hippie-Land – Holy Man Opens S.F. Temple.” The article began, “A holy man from India, described by his friend and beat poet Allen Ginsberg as one of the more conservative leaders of his faith, launched a kind of evangelistic effort yesterday in the heart of San Francisco’s hippie haven.”

| | El periódico más grande de San Francisco, el Chronicle, también publicó un artículo: “Svāmī en tierra de hippies - Hombre santo abre templo en San Francisco..” El artículo comenzaba: “Un hombre santo de la India, descrito por su amigo y poeta beat Allen Ginsberg como uno de los líderes más conservadores de su fe, lanzó ayer una especie de esfuerzo evangelístico en el corazón del paraíso hippie de San Francisco".

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda objected to being called conservative. He was indignant: “Conservative? How is that?”

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda se opuso a ser llamado conservador. Estaba indignado: “¿Conservador? ¿Como es eso?"

|  | “In respect to sex and drugs,” Mukunda suggested.

| | "Con respecto al sexo y las drogas", sugirió Mukunda.

|  | “Of course, we are conservative in that sense,” Prabhupāda said. “That simply means we are following śāstra. We cannot depart from Bhagavad-gītā. But conservative we are not. Caitanya Mahāprabhu was so strict that He would not even look on a woman, but we are accepting everyone into this movement, regardless of sex, caste, position, or whatever. Everyone is invited to come chant Hare Kṛṣṇa. This is Caitanya Mahāprabhu’s munificence, His liberality. No, we are not conservative.”

| | "Por supuesto, somos conservadores en ese sentido", dijo Prabhupāda. “Eso simplemente significa que estamos siguiendo el śāstra. No podemos apartarnos del Bhagavad-gītā. Pero conservadores no lo somos. Caitanya Mahāprabhu era tan estricto que ni siquiera miraría a una mujer, pero estamos aceptando a todos en este movimiento, sin importar el sexo, la casta, la posición o lo que sea. Todos están invitados a venir a cantar Hare Kṛṣṇa. Ésta es la generosidad de Caitanya Mahāprabhu, Su generosidad. No, no somos conservadores".

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda rose from bed and turned on the light. It was 1 A.M. Although the alarm had not sounded and no one had come to wake him, he had risen on his own. The apartment was cold and quiet. Wrapping his cādara around his shoulders, he sat quietly at his makeshift desk (a trunk filled with manuscripts) and in deep concentration chanted the Hare Kṛṣṇa mantra on his beads.

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda se levantó de la cama y encendió la luz. Era la 1 de la madrugada. Aunque la alarma no había sonado y nadie había venido a despertarlo, se había levantado solo. El apartamento estaba frío y silencioso. Envolviendo su cādara alrededor de sus hombros, se sentó en silencio en su escritorio improvisado (un baúl lleno de manuscritos) y en profunda concentración cantó el mantra Hare Kṛṣṇa en sus cuentas.

|  | After an hour of chanting, Śrīla Prabhupāda turned to his writing. Although two years had passed since he had published a book (the third and final volume of the First Canto of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam), he had daily been working, sometimes on his translation and commentary of the Second Canto but mostly on Bhagavad-gītā. In the 1940s in India he had written an entire Bhagavad-gītā translation and commentary, but his only copy had mysteriously disappeared. Then in 1965, after a few months in America, he had begun again, starting with the Introduction, which he had composed in his room on Seventy-second Street in New York. Now thousands of manuscript pages filled his trunk, completing his Bhagavad-gītā. If his New York disciple Hayagrīva, formerly an English professor, could edit it, and if some of the other disciples could get it published, that would be an important achievement.

| | Después de una hora de cantar, Śrīla Prabhupāda se dedicó a escribir. Aunque habían pasado dos años desde que publicó un libro (el tercer y último volumen del Primer Canto del Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam), había estado trabajando a diario, a veces en su traducción y comentario del Segundo Canto, pero sobre todo en el Bhagavad-gītā. En la década de 1940 en la India había escrito una traducción y un comentario completos del Bhagavad-gītā, pero su única copia había desaparecido misteriosamente. Luego, en 1965, después de unos meses en Estados Unidos, comenzó de nuevo, iniciando con la Introducción, que había compuesto en su habitación de la calle Setenta y dos de Nueva York. Ahora miles de páginas manuscritas llenaban su baúl, completando su Bhagavad-gītā. Si su discípulo de Nueva York Hayagrīva, ex profesor de inglés, pudiera editarlo y si algunos de los otros discípulos pudieran publicarlo, eso sería un logro importante.

|  | But publishing books in America seemed difficult – more difficult than in India. Even though in India he had been alone, he had managed to publish three volumes in three years. Here in America he had many followers; but many followers meant increased responsibilities. And none of his followers as yet seemed seriously inclined to take up typing, editing, and dealing with American businessmen. Yet despite the dim prospects for publishing his Bhagavad-gītā, Śrīla Prabhupāda had begun translating another book, Caitanya-caritāmṛta, the principal Vaiṣṇava scripture on the life and teachings of Lord Caitanya.

| | Pero publicar libros en Estados Unidos parecía difícil, más difícil que en India. Aunque en la India estando solo, logró publicar tres volúmenes en tres años. Aquí en Norteamérica tuvo muchos seguidores; pero muchos seguidores significaron mayores responsabilidades. Y ninguno de sus seguidores parecía todavía estar seriamente inclinado a escribir, editar y tratar con empresarios estadounidenses. Sin embargo, a pesar de las escasas perspectivas de publicar su Bhagavad-gītā, Śrīla Prabhupāda había comenzado a traducir otro libro, El Caitanya-caritāmṛta, la principal escritura vaiṣṇava sobre la vida y las enseñanzas del Señor Caitanya.

|  | Putting on his reading glasses, Prabhupāda opened his books and turned on the dictating machine. He studied the Bengali and Sanskrit texts, then picked up the microphone, flicked the switch to record, flashing on a small red light, and began speaking: “While the Lord was going, chanting and dancing, …” (he spoke no more than a phrase at a time, flicking the switch, pausing, and then dictating again) “thousands of people were following Him, … and some of them were laughing, some were dancing, … and some singing. … Some of them were falling on the ground offering obeisances to the Lord.” Speaking and pausing, clicking the switch on and off, he would sit straight, sometimes gently rocking and nodding his head as he urged forward his words. Or he would bend low over his books, carefully studying them through his reading glasses.

| | Prabhupāda se puso las gafas para leer, abrió sus libros y encendió la máquina de dictar. Estudió los textos en bengalí y sánscrito, luego tomó el micrófono, pulsó el interruptor para grabar, parpadeando en una pequeña luz roja y comenzó a hablar: “Mientras el Señor iba, cantando y bailando....” una frase a la vez, accionando el interruptor, haciendo una pausa y luego dictando de nuevo) “miles de personas lo seguían... algunos de ellos se reían, otros bailaban ... algunos cantaban... algunos de ellos caían al suelo ofreciendo reverencias al Señor”. Hablando y haciendo pausas, haciendo clic en el interruptor de encendido y apagado, se sentaba derecho, a veces meciéndose suavemente y asintiendo con la cabeza mientras impulsaba sus palabras. O se inclinaba sobre sus libros, estudiándolos cuidadosamente a través de sus lentes de lectura.

|  | An hour passed, and Prabhupāda worked on. The building was dark except for Prabhupāda’s lamp and quiet except for the sound of his voice and the click and hum of the dictating machine. He wore a faded peach turtleneck jersey beneath his gray wool cādara, and since he had just risen from bed, his saffron dhotī was wrinkled. Without having washed his face or gone to the bathroom he sat, absorbed in his work. At least for these few rare hours, the street and the Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa temple were quiet.

| | Pasó una hora y Prabhupāda siguió trabajando. El edificio estaba oscuro excepto por la lámpara de Prabhupāda y silencioso excepto por el sonido de su voz y el clic y zumbido de la máquina dictadora. Llevaba un jersey de cuello alto color melocotón descolorido debajo de su cādara de lana gris, como acababa de levantarse de la cama, su dhoti azafrán estaba arrugado. Sin lavarse la cara ni ir al baño se sentó absorto en su trabajo. Durante estas raras horas, la calle y el templo de Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa estaban en silencio.

|  | This situation – with the night dark, the surroundings quiet, and him at his transcendental literary work – was not much different from his early-morning hours in his room at the Rādhā-Dāmodara temple in Vṛndāvana, India. There, of course, he had had no dictating machine, but he had worked during the same hours and from the same text, Caitanya-caritāmṛta. Once he had begun a verse-by-verse translation with commentary, and another time he had written essays on the text. Now, having just arrived in this corner of the world, so remote from the scenes of Lord Caitanya’s pastimes, he was beginning the first chapter of a new English version of Caitanya-caritāmṛta. He called it Teachings of Lord Caitanya.

| | Esta situación, con la noche oscura, el entorno tranquilo y él en su trascendental obra literaria, no era muy diferente de sus horas de madrugada en su habitación en el templo Rādhā-Dāmodara en Vṛndāvana, India. Allí, por supuesto, no había tenido una máquina de dictar, pero había trabajado durante las mismas horas y con el mismo texto, El Caitanya-caritāmṛta. A veces comenzado una traducción verso por verso con comentarios, otras veces escribiendo ensayos sobre el texto. Ahora, recién llegado a este rincón del mundo, tan alejado de las escenas de los pasatiempos del Señor Caitanya, comenzaba el primer capítulo de una nueva versión en inglés del Caitanya-caritāmṛta. Lo llamó Enseñanzas del Señor Caitanya.

|  | He was following what had become a vital routine in his life: rising early and writing the paramparā message of Kṛṣṇa consciousness. Putting aside all other considerations, disregarding present circumstances, he would merge into the timeless message of transcendental knowledge. This was his most important service to Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī. The thought of producing more books and distributing them widely inspired him to rise every night and translate.

| | Estaba siguiendo lo que se había convertido en una rutina vital en su vida: levantarse temprano y escribir el mensaje paramparā de la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa. Dejando a un lado todas las demás consideraciones, sin tener en cuenta las circunstancias presentes, se fundiría en el mensaje eterno del conocimiento trascendental. Este fue su servicio más importante para Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī. La idea de producir más libros y distribuirlos ampliamente lo inspiró a levantarse cada noche y traducir.

|  | Prabhupāda worked until dawn. Then he stopped and prepared himself to go down to the temple for the morning meeting.

| | Prabhupāda trabajó hasta el amanecer. Luego se detuvo y se preparó para bajar al templo para la reunión de la mañana.

|  | Though some of the New York disciples had objected, Śrīla Prabhupāda was still scheduled for the Mantra-Rock Dance at the Avalon Ballroom. It wasn’t proper, they had said, for the devotees out in San Francisco to ask their spiritual master to go to such a place. It would mean amplified guitars, pounding drums, wild light shows, and hundreds of drugged hippies. How could his pure message be heard in such a place?

| | Aunque algunos de los discípulos de Nueva York se habían opuesto, Śrīla Prabhupāda aún estaba programado para la Danza Mantra-Rock en el salón de baile Avalon. No era apropiado, habían dicho, que los devotos de San Francisco pidieran a su maestro espiritual que fuera a ese lugar. Significaría guitarras amplificadas, tambores fuertes, espectáculos de luces salvajes y cientos de hippies drogados. ¿Cómo podía escucharse su mensaje puro en un lugar así?

|  | But in San Francisco Mukunda and others had been working on the Mantra-Rock Dance for months. It would draw thousands of young people, and the San Francisco Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa Temple stood to make thousands of dollars. So although among his New York disciples Śrīla Prabhupāda had expressed uncertainty, he now said nothing to deter the enthusiasm of his San Francisco followers.

| | Pero en San Francisco, Mukunda y otros habían estado trabajando en Mantra-Rock Dance durante meses. Atraería a miles de jóvenes y el Templo Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa de San Francisco estaba listo para generar miles de dólares. Entonces, aunque entre sus discípulos de Nueva York Śrīla Prabhupāda había expresado incertidumbre, ahora no dijo nada para disuadir el entusiasmo de sus seguidores de San Francisco.

|  | Sam Speerstra, Mukunda’s friend and one of the Mantra-Rock organizers, explained the idea to Hayagrīva, who had just arrived from New York: “There’s a whole new school of San Francisco music opening up. The Grateful Dead have already cut their first record. Their offer to do this dance is a great publicity boost just when we need it.”

| | Sam Speerstra, amigo de Mukunda y uno de los organizadores de Mantra-Rock, le explicó la idea a Hayagrīva, que acababa de llegar de Nueva York: “Se está abriendo una escuela completamente nueva de música en San Francisco. The Grateful Dead ya ha grabado su primer disco. Su oferta para hacer este baile es un gran impulso publicitario justo cuando lo necesitamos".

|  | “But Svāmīji says that even Ravi Shankar is māyā,” Hayagrīva said.

| | “Pero Svāmīji dice que incluso Ravi Shankar es māyā”, dijo Hayagrīva.

|  | “Oh, it’s all been arranged,” Sam assured him. “All the bands will be onstage, and Allen Ginsberg will introduce Svāmīji to San Francisco. Svāmīji will talk and then chant Hare Kṛṣṇa, with the bands joining in. Then he leaves. There should be around four thousand people there.”

| | "Oh, todo está arreglado", le aseguró Sam. “Todas las bandas estarán en el escenario y Allen Ginsberg presentará a Svāmīji en San Francisco. Svāmīji hablará y cantará Hare Kṛṣṇa, con las bandas uniéndose. Luego se irá. Deberá haber unas cuatro mil personas allí".

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda knew he would not compromise himself; he would go, chant, and then leave. The important thing was to spread the chanting of Hare Kṛṣṇa. If thousands of young people gathering to hear rock music could be engaged in hearing and chanting the names of God, then what was the harm? As a preacher, Prabhupāda was prepared to go anywhere to spread Kṛṣṇa consciousness. Since chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa was absolute, one who heard or chanted the names of Kṛṣṇa – anyone, anywhere, in any condition – could be saved from falling to the lower species in the next life. These young hippies wanted something spiritual, but they had no direction. They were confused, accepting hallucinations as spiritual visions. But they were seeking genuine spiritual life, just like many of the young people on the Lower East Side. Prabhupāda decided he would go; his disciples wanted him to, and he was their servant and the servant of Lord Caitanya.

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda sabía que no se comprometería; Iría, cantaría y luego se iría. Lo importante era difundir el canto de Hare Kṛṣṇa. Si miles de jóvenes que se reunían para escuchar música rock podían dedicarse a escuchar y cantar los nombres de Dios, ¿cuál era el daño? Como predicador, Prabhupāda estaba preparado para ir a cualquier lugar para difundir la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa. Dado que cantar Hare Kṛṣṇa era absoluto, alguien que escuchara o cantaba los nombres de Kṛṣṇa, cualquiera, en cualquier lugar y en cualquier condición, podía salvarse de caer a las especies inferiores en la próxima vida. Estos jóvenes hippies querían algo espiritual, pero no tenían dirección. Estaban confundidos, aceptando las alucinaciones como visiones espirituales. Pero buscaban una vida espiritual genuina, al igual que muchos de los jóvenes del Lade Este Bajo. Prabhupāda decidió que iría; sus discípulos querían que lo hiciera, él era su sirviente y el sirviente del Señor Caitanya.

|  | Mukunda, Sam, and Harvey Cohen had already met with rock entrepreneur Chet Helms, who had agreed that they could use his Avalon Ballroom and that, if they could get the bands to come, everything above the cost for the groups, the security, and a few other basics would go as profit for the San Francisco Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa Temple. Mukunda and Sam had then gone calling on the music groups, most of whom lived in the Bay Area, and one after another the exciting new San Francisco rock bands – the Grateful Dead, Moby Grape, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service – had agreed to appear with Svāmī Bhaktivedanta for the minimum wage of $250 per group. And Allen Ginsberg had agreed. The lineup was complete.

| | Mukunda, Sam y Harvey Cohen ya se habían reunido con el empresario de rock Chet Helms, quien acordó que podrían usar su Avalon Ballroom y que, si podían conseguir que vinieran las bandas, todo por encima del costo de los grupos, la seguridad y algunos otros elementos básicos servirían como beneficio para el Templo Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa de San Francisco. Mukunda y Sam fueron a visitar a los grupos de música, la mayoría de los cuales vivían en el Área de la Bahía, uno tras otro a las nuevas y emocionantes bandas de rock de San Francisco: Grateful Dead, Moby Grape, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service - acordaron aparecer con Svāmī Bhaktivedanta por el salario mínimo de 250 dólares por grupo. Allen Ginsberg estuvo de acuerdo. La alineación estaba completa.

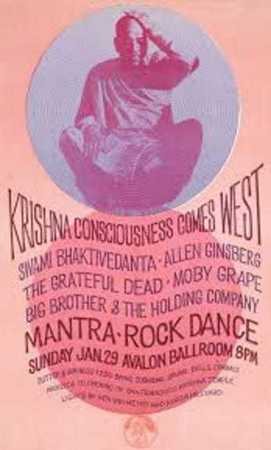

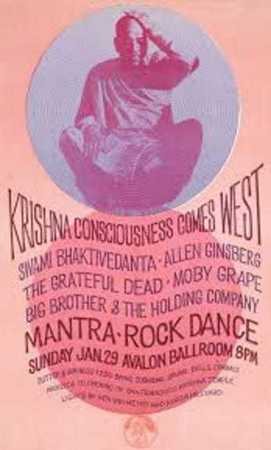

|  | In San Francisco every rock concert had an art poster, many of them designed by the psychedelic artist called Mouse. One thing about Mouse’s posters was that it was difficult to tell where the letters left off and the background began. He used dissonant colors that made his posters seem to flash on and off. Borrowing from this tradition, Harvey Cohen had created a unique poster – KRISHNA CONSCIOUSNESS COMES WEST – using red and blue concentric circles and a candid photo of Svāmīji smiling in Tompkins Square Park. The devotees put the posters up all over town.

| | En San Francisco, cada concierto de rock tenía un cartel de arte, muchos de ellos diseñados por el artista psicodélico llamado Mouse. Una cosa acerca de los carteles de Mouse era que era difícil saber dónde terminaban las letras y comenzaba el fondo. Usó colores disonantes que hacían que sus carteles parecieran parpadear. Tomando prestado de esta tradición, Harvey Cohen creó un póster único: LA CONCIENCIA DE KRISHNA VIENE AL OESTE, usando círculos concéntricos rojos y azules y una foto sincera de Svāmīji sonriendo en Tompkins Square Park. Los devotos colocaron los carteles por toda la ciudad.

|  | Hayagrīva and Mukunda went to discuss the program for the Mantra-Rock Dance with Allen Ginsberg. Allen was already well known as an advocate of the Hare Kṛṣṇa mantra; in fact, acquaintances would often greet him with “Hare Kṛṣṇa!” when he walked on Haight Street. And he was known to visit and recommend that others visit the Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa Temple. Hayagrīva, whose full beard and long hair rivaled Allen’s, was concerned about the melody Allen would use when he chanted with Svāmīji. “I think the melody you use,” Hayagrīva said, “is too difficult for good chanting.”

| | Hayagrīva y Mukunda fueron a discutir el programa del Mantra-Rock Dance con Allen Ginsberg. Allen ya era bien conocido como defensor del mantra Hare Kṛṣṇa; de hecho, los conocidos a menudo lo saludaban con. “¡Hare Kṛṣṇa!.” cuando caminaba por la Calle Haight. Era conocido por visitar y recomendar que otros visitaran el Templo Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa. Hayagrīva, cuya barba llena y cabello largo rivalizaba con el de Allen, estaba preocupado por la melodía que Allen usaría cuando cantaba con Svāmīji. “Creo que la melodía que usas", dijo Hayagrīva,. “es demasiado difícil para cantarla bien".

|  | “Maybe,” Allen admitted, “but that’s the melody I first heard in India. A wonderful lady saint was chanting it. I’m quite accustomed to it, and it’s the only one I can sing convincingly.”

| | "Tal vez", admitió Allen,. “pero esa es la melodía que escuché por primera vez en la India. Una maravillosa dama santa lo cantaba. Estoy bastante acostumbrado a eso, y es el único que puedo cantar de manera convincente".

|  | With only a few days remaining before the Mantra-Rock Dance, Allen came to an early-morning kīrtana at the temple and later joined Śrīla Prabhupāda upstairs in his room. A few devotees were sitting with Prabhupāda eating Indian sweets when Allen came to the door. He and Prabhupāda smiled and exchanged greetings, and Prabhupāda offered him a sweet, remarking that Mr. Ginsberg was up very early.

| | Con solo unos pocos días antes de la Danza Mantra-Rock, Allen llegó a un kīrtana temprano en la mañana en el templo y luego se unió a Śrīla Prabhupāda arriba en su habitación. Algunos devotos estaban sentados con Prabhupāda comiendo dulces indios cuando Allen llegó a la puerta. Él y Prabhupāda sonrieron e intercambiaron saludos, Prabhupāda le ofreció un dulce y comentó que el Sr. Ginsberg se había levantado muy temprano.

|  | “Yes,” Allen replied, “the phone hasn’t stopped ringing since I arrived in San Francisco.”

| | "Sí", respondió Allen,. “el teléfono no ha dejado de sonar desde que llegué a San Francisco".

|  | “That is what happens when one becomes famous,” said Prabhupāda. “That was the tragedy of Mahatma Gandhi also. Wherever he went, thousands of people would crowd about him, chanting, ‘Mahatma Gandhi kī jaya! Mahatma Gandhi kī jaya!’ The gentleman could not sleep.”

| | “Eso es lo que sucede cuando uno se vuelve famoso”, dijo Prabhupāda. “Esa fue también la tragedia de Mahatma Gandhi. Dondequiera que fuera, miles de personas se agolpaban a su alrededor, cantando: “¡Mahatma Gandhi kī jaya! ¡Mahatma Gandhi kī jaya!. “El caballero no podía dormir".

|  | “Well, at least it got me up for kīrtana this morning,” said Allen.

| | “Bueno, al menos me despertó para el kīrtana de esta mañana”, dijo Allen.

|  | “Yes, that is good.”

| | "Sí, eso es bueno."

|  | The conversation turned to the upcoming program at the Avalon Ballroom. “Don’t you think there’s a possibility of chanting a tune that would be more appealing to Western ears?” Allen asked.

| | La conversación se centró en el próximo programa en el Salón Avalon. “¿No crees que existe la posibilidad de cantar una melodía que sería más atractiva para los oídos occidentales?.” Preguntó Allen.

|  | “Any tune will do,” said Prabhupāda. “Melody is not important. What is important is that you will chant Hare Kṛṣṇa. It can be in the tune of your own country. That doesn’t matter.”

| | “Cualquier melodía servirá”, dijo Prabhupāda. “La melodía no es importante. Lo importante es que cantes Hare Kṛṣṇa. Puede estar en la sintonía de su propio país. Eso no importa".

|  | Prabhupāda and Allen also talked about the meaning of the word hippie, and Allen mentioned something about taking LSD. Prabhupāda replied that LSD created dependence and was not necessary for a person in Kṛṣṇa consciousness. “Kṛṣṇa consciousness resolves everything,” Prabhupāda said. “Nothing else is needed.”

| | Prabhupāda y Allen también hablaron sobre el significado de la palabra hippie, Allen mencionó algo sobre tomar LSD. Prabhupāda respondió que el LSD creaba dependencia y no era necesario para una persona con Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa. “La Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa lo resuelve todo”, dijo Prabhupāda. “No se necesita nada más".

|  | At the Mantra-Rock Dance there would be a multimedia light show by the biggest names in the art, Ben Van Meter and Roger Hillyard. Ben and Roger were expert at using simultaneous strobe lights, films, and slide shows to fill an auditorium with optical effects reminiscent of LSD visions. Mukunda had given them many slides of Kṛṣṇa to use during the kīrtana. One evening, Ben and Roger came to see Svāmīji in his apartment.

| | En el Mantra-Rock Dance habría un espectáculo de luces multimedia de los nombres más importantes del arte, Ben Van Meter y Roger Hillyard. Ben y Roger eran expertos en el uso simultáneo de luces estroboscópicas, películas y presentaciones de diapositivas para llenar un auditorio con efectos ópticos que recuerdan las visiones de LSD. Mukunda les había dado muchas diapositivas de Kṛṣṇa para que las usaran durante el kīrtana. Una noche, Ben y Roger fueron a ver a Svāmīji a su apartamento.

|  | Roger Hillyard: He was great. I was really impressed. It wasn’t the way he looked, the way he acted, or the way he dressed, but it was his total being. Svāmīji was very serene and very humorous, and at the same time obviously very wise and in tune, enlightened. He had the ability to relate to a lot of different kinds of people. I was thinking, “Some of this must be really strange for this person – to come to the United States and end up in the middle of Haight-Ashbury with a storefront for an āśrama and a lot of very strange people around.” And yet he was totally right there, right there with everybody.

| | Roger Hillyard: Estuvo genial. Me quedé realmente impresionado. No era la forma en que se veía, la forma en que actuaba o la forma en que se vestía, sino su ser total. Svāmīji era muy sereno y muy grato, al mismo tiempo obviamente muy sabio y afinado, iluminado. Tenía la capacidad de relacionarse con muchos tipos diferentes de personas. Estaba pensando: “Algo de esto debe ser realmente extraño para esta persona: venir a los Estados Unidos y terminar en el medio de Haight-Ashbury con un local para un āśrama y mucha gente muy extraña alrededor". Sin embargo, estaba totalmente ahí, justo ahí con todos.

|  | On the night of the Mantra-Rock Dance, while the stage crew set up equipment and tested the sound system and Ben and Roger organized their light show upstairs, Mukunda and others collected tickets at the door. People lined up all the way down the street and around the block, waiting for tickets at $2.50 USD a piece. Attendance would be good, a capacity crowd, and most of the local luminaries were coming. LSD pioneer Timothy Leary arrived and was given a special seat onstage. Svāmī Kriyananda came, carrying a tamboura. A man wearing a top hat and a suit with a silk sash that said SAN FRANCISCO arrived, claiming to be the mayor. At the door, Mukunda stopped a respectably dressed young man who didn’t have a ticket. But then someone tapped Mukunda on the shoulder: “Let him in. It’s all right. He’s Owsley.” Mukunda apologized and submitted, allowing Augustus Owsley Stanley II, folk hero and famous synthesizer of LSD, to enter without a ticket.

| | En la noche del Mantra-Rock Dance, mientras el equipo del escenario instalaba el equipo y probaba el sistema de sonido y Ben y Roger organizaban su espectáculo de luces arriba, Mukunda y otros recogían boletos en la puerta. La gente se alineó a lo largo de la calle y alrededor de la cuadra, esperando boletos a $2.50 USD cada uno. La asistencia sería buena, una multitud llena y la mayoría de las luminarias locales vendrían. El pionero del LSD, Timothy Leary, llegó y se le dio un asiento especial en el escenario. Svāmī Kriyananda llegó con una tamboura. Llegó un hombre con sombrero de copa y traje con fajín de seda que decía SAN FRANCISCO, que decía ser el alcalde. En la puerta, Mukunda detuvo a un joven elegantemente vestido que no tenía boleto. Pero entonces alguien tocó a Mukunda en el hombro: “Déjalo entrar. Está bien. Él es Owsley". Mukunda se disculpó y se sometió, permitiendo que Augustus Owsley Stanley II, héroe popular y famoso sintetizador de LSD, ingresara sin boleto.

|  | Almost everyone who came wore bright or unusual costumes: tribal robes, Mexican ponchos, Indian kurtās, “God’s-eyes,” feathers, and beads. Some hippies brought their own flutes, lutes, gourds, drums, rattles, horns, and guitars. The Hell’s Angels, dirty-haired, wearing jeans, boots, and denim jackets and accompanied by their women, made their entrance, carrying chains, smoking cigarettes, and displaying their regalia of German helmets, emblazoned emblems, and so on – everything but their motorcycles, which they had parked outside.

| | Casi todos los que asistieron vestían trajes brillantes o inusuales: túnicas tribales, ponchos mexicanos, kurtās indios,. “ojos de Dios", plumas y cuentas. Algunos hippies trajeron sus propias flautas, laúdes, calabazas, tambores, sonajeros, trompas y guitarras. Los Ángeles del Infierno, de pelo sucio, con jeans, botas y chaquetas de mezclilla y acompañados de sus mujeres, hicieron su entrada, portando cadenas, fumando cigarrillos y exhibiendo sus insignias de cascos alemanes, emblemas blasonados, etc., todo menos sus motocicletas, que habían estacionado afuera.

|  | The devotees began a warm-up kīrtana onstage, dancing the way Svāmīji had shown them. Incense poured from the stage and from the corners of the large ballroom. And although most in the audience were high on drugs, the atmosphere was calm; they had come seeking a spiritual experience. As the chanting began, very melodiously, some of the musicians took part by playing their instruments. The light show began: strobe lights flashed, colored balls bounced back and forth to the beat of the music, large blobs of pulsing color splurted across the floor, walls, and ceiling.

| | Los devotos comenzaron un kīrtana de calentamiento en el escenario, bailando como les había mostrado Svāmīji. El incienso se derramaba desde el escenario y desde las esquinas del gran salón de baile. Aunque la mayoría de la audiencia estaba drogada, la atmósfera era tranquila; habían venido buscando una experiencia espiritual. Cuando comenzó el canto, muy melodiosamente, algunos de los músicos participaron tocando sus instrumentos. El espectáculo de luces comenzó: las luces estroboscópicas parpadearon, las bolas de colores rebotaron de un lado a otro al ritmo de la música, grandes manchas de colores vibrantes se esparcieron por el suelo, las paredes y el techo.

|  | A little after eight o’clock, Moby Grape took the stage. With heavy electric guitars, electric bass, and two drummers, they launched into their first number. The large speakers shook the ballroom with their vibrations, and a roar of approval rose from the audience.

| | Poco después de las ocho, Moby Grape subió al escenario. Con guitarras eléctricas pesadas, bajo eléctrico y dos bateristas, lanzaron su primer número. Los grandes altavoces sacudieron el salón de baile con sus vibraciones y un rugido de aprobación se elevó de la audiencia.

|  | Around nine-thirty, Prabhupāda left his Frederick Street apartment and got into the back seat of Harvey’s Cadillac. He was dressed in his usual saffron robes, and around his neck he wore a garland of gardenias, whose sweet aroma filled the car. On the way to the Avalon he talked about the need to open more centers.

| | Alrededor de las nueve y media, Prabhupāda salió de su apartamento de la Calle Frederick y se subió al asiento trasero del Cadillac de Harvey. Iba vestido con su habitual túnica azafrán, alrededor del cuello llevaba una guirnalda de gardenias, cuyo dulce aroma llenaba el auto. De camino al Avalon habló sobre la necesidad de abrir más centros.

|  | At ten o’clock Prabhupāda walked up the stairs of the Avalon, followed by Kīrtanānanda and Ranchor. As he entered the ballroom, devotees blew conchshells, someone began a drum roll, and the crowd parted down the center, all the way from the entrance to the stage, opening a path for him to walk. With his head held high, Prabhupāda seemed to float by as he walked through the strange milieu, making his way across the ballroom floor to the stage.

| | A las diez en punto, Prabhupāda subió las escaleras del Avalon, seguido por Kīrtanānanda y Ranchor. Cuando entró al salón de baile, los devotos soplaron caracolas, alguien comenzó a redoblar y la multitud se separó por el centro, desde la entrada al escenario, abriendo un camino para que él caminara. Con la cabeza en alto, Prabhupāda parecía flotar mientras caminaba por el extraño entorno, abriéndose paso por el suelo del salón de baile hasta el escenario.

|  | Suddenly the light show changed. Pictures of Kṛṣṇa and His pastimes flashed onto the wall: Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna riding together on Arjuna’s chariot, Kṛṣṇa eating butter, Kṛṣṇa subduing the whirlwind demon, Kṛṣṇa playing the flute. As Prabhupāda walked through the crowd, everyone stood, applauding and cheering. He climbed the stairs and seated himself softly on a waiting cushion. The crowd quieted.

| | De repente, el espectáculo de luces cambió. Imágenes de Kṛṣṇa y Sus pasatiempos aparecieron en la pared: Kṛṣṇa y Arjuna montados juntos en el carro de Arjuna, Kṛṣṇa comiendo mantequilla, Kṛṣṇa sometiendo al demonio torbellino, Kṛṣṇa tocando la flauta. Mientras Prabhupāda caminaba entre la multitud, todos se pusieron de pie, aplaudiendo y vitoreando. Subió las escaleras y se sentó suavemente en un cojín de espera. La multitud se calló.

|  | Looking over at Allen Ginsberg, Prabhupāda said, “You can speak something about the mantra.”

| | Mirando a Allen Ginsberg, Prabhupāda dijo: “Puedes hablar algo sobre el mantra".

|  | Allen began to tell of his understanding and experience with the Hare Kṛṣṇa mantra. He told how Svāmīji had opened a storefront on Second Avenue and had chanted Hare Kṛṣṇa in Tompkins Square Park. And he invited everyone to the Frederick Street temple. “I especially recommend the early-morning kīrtanas,” he said, “for those who, coming down from LSD, want to stabilize their consciousness on reentry.”

| | Allen comenzó a hablar de su comprensión y experiencia con el mantra Hare Kṛṣṇa. Contó cómo Svāmīji abrió un local en la Segunda Avenida y cantó Hare Kṛṣṇa en el Parque Tompkins. E invitó a todos al templo de la Calle Frederick. “Recomiendo especialmente las kīrtanas de la madrugada", dijo,. “para aquellos que, al bajar del LSD, quieran estabilizar su conciencia al volver a entrar".

|  | Prabhupāda spoke, giving a brief history of the mantra. Then he looked over at Allen again: “You may chant.”

| | Prabhupāda habló, dando una breve historia del mantra. Luego volvió a mirar a Allen: “Puedes cantar".

|  | Allen began playing his harmonium and chanting into the microphone, singing the tune he had brought from India. Gradually more and more people in the audience caught on and began chanting. As the kīrtana continued and the audience got increasingly enthusiastic, musicians from the various bands came onstage to join in. Ranchor, a fair drummer, began playing Moby Grape’s drums. Some of the bass and other guitar players joined in as the devotees and a large group of hippies mounted the stage. The multicolored oil slicks pulsed, and the balls bounced back and forth to the beat of the mantra, now projected onto the wall: Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa, Hare Hare / Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. As the chanting spread throughout the hall, some of the hippies got to their feet, held hands, and danced.

| | Allen comenzó a tocar su armonio y a cantar en el micrófono, cantando la melodía que había traído de la India. Gradualmente, más y más personas en la audiencia se dieron cuenta y comenzaron a cantar. A medida que continuaba el kīrtana y el público se entusiasmaba cada vez más, los músicos de las distintas bandas subían al escenario para unirse. Ranchor, un buen baterista, comenzó a tocar la batería de Moby Grape. Algunos de los bajistas y otros guitarristas se unieron cuando los devotos y un gran grupo de hippies subieron al escenario. Las manchas de aceite multicolores pulsaban y las bolas rebotaban hacia adelante y hacia atrás al ritmo del mantra, ahora proyectado en la pared: Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. A medida que los cánticos se extendían por el salón, algunos de los hippies se levantaron, se tomaron de las manos y bailaron.

|  | Allen Ginsberg: We sang Hare Kṛṣṇa all evening. It was absolutely great – an open thing. It was the height of the Haight-Ashbury spiritual enthusiasm. It was the first time that there had been a music scene in San Francisco where everybody could be part of it and participate. Everybody could sing and dance rather than listen to other people sing and dance.

| | Allen Ginsberg: Cantamos Hare Kṛṣṇa toda la noche. Fue absolutamente genial, algo abierto. Fue el colmo del entusiasmo espiritual de Haight-Ashbury. Era la primera vez que había una escena musical en San Francisco donde todos podían ser parte y participar. Todo el mundo podría cantar y bailar en lugar de escuchar a otras personas cantar y bailar.

|  | Jānakī: People didn’t know what they were chanting for. But to see that many people chanting – even though most of them were intoxicated – made Svāmīji very happy. He loved to see the people chanting.

| | Jānakī: La gente no sabía para qué cantaba. Pero ver a tanta gente cantando —aunque la mayoría de ellos estaban intoxicados— hizo que Svāmīji se sintiera muy feliz. Le encantaba ver a la gente cantando.

|  | Hayagrīva: Standing in front of the bands, I could hardly hear. But above all, I could make out the chanting of Hare Kṛṣṇa, building steadily. On the wall behind, a slide projected a huge picture of Kṛṣṇa in a golden helmet with a peacock feather, a flute in His hand.

| | Hayagrīva: De pie frente a las bandas, apenas podía escuchar. Pero sobre todo, pude distinguir el canto de Hare Kṛṣṇa, aumentando de manera constante. En la pared de atrás, una diapositiva proyectaba una gran imagen de Kṛṣṇa con un casco dorado con una pluma de pavo real, una flauta en Su mano.

|  | Then Śrīla Prabhupāda stood up, lifted his arms, and began to dance. He gestured for everyone to join him, and those who were still seated stood up and began dancing and chanting and swaying back and forth, following Prabhupāda’s gentle dance.

| | Entonces Śrīla Prabhupāda se puso de pie, levantó los brazos y comenzó a bailar. Hizo un gesto para que todos se unieran a él, los que todavía estaban sentados se pusieron de pie y comenzaron a bailar, cantar y balancearse de un lado a otro, siguiendo la suave danza de Prabhupāda.

|  | Roger Segal: The ballroom appeared as if it was a human field of wheat blowing in the wind. It produced a calm feeling in contrast to the Avalon Ballroom atmosphere of gyrating energies. The chanting of Hare Kṛṣṇa continued for over an hour, and finally everyone was jumping and yelling, even crying and shouting.

| | Roger Segal: El salón de baile parecía como si fuera un campo humano de trigo movido por el viento. Produjo una sensación de calma en contraste con la atmósfera de energías giratorias del Salón Avalon. El canto de Hare Kṛṣṇa continuó durante más de una hora, finalmente, todos saltaron y gritaron, incluso lloraron y gritaron.

|  | Someone placed a microphone before Śrīla Prabhupāda, and his voice resounded strongly over the powerful sound system. The tempo quickened. Śrīla Prabhupāda was perspiring profusely. Kīrtanānanda insisted that the kīrtana stop. Svāmīji was too old for this, he said; it might be harmful. But the chanting continued, faster and faster, until the words of the mantra finally became indistinguishable amidst the amplified music and the chorus of thousands of voices.

| | Alguien colocó un micrófono ante Śrīla Prabhupāda, su voz resonó con fuerza sobre el poderoso sistema de sonido. El ritmo se aceleró. Śrīla Prabhupāda sudaba profusamente. Kīrtanānanda insistió en que el kīrtana se detuviera. Svāmīji era demasiado mayor para esto, dijo; podría ser perjudicial. Pero el canto continuó, cada vez más rápido, hasta que las palabras del mantra finalmente se volvieron indistinguibles en medio de la música amplificada y el coro de miles de voces.

|  | Then suddenly it ended. And all that could be heard was the loud hum of the amplifiers and Śrīla Prabhupāda’s voice, ringing out, offering obeisances to his spiritual master: “Oṁ Viṣṇupāda Paramahaṁsa Parivrājakācārya Aṣṭottara-śata Śrī Śrīmad Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Gosvāmī Mahārāja kī jaya! ... All glories to the assembled devotees!”

| | Entonces, de repente, terminó. Todo lo que se pudo escuchar fue el fuerte zumbido de los amplificadores y la voz de Śrīla Prabhupāda, resonando, ofreciendo reverencias a su maestro espiritual: “¡Oṁ Viṣṇupāda Paramahaṁsa Parivrājakācārya Aṣṭottara-śata Śrī Śrīmad Bhaktisiddaya Gāoshanta kānta! ... ¡Todas las glorias a los devotos reunidos!"

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda made his way offstage, through the heavy smoke and crowds, and down the front stairs, with Kīrtanānanda and Ranchor close behind him. Allen announced the next rock group.

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda salió del escenario a través del denso humo y la multitud, bajó las escaleras delanteras, con Kīrtanānanda y Ranchor muy cerca de él. Allen anunció el próximo grupo de rock.

|  | As Svāmīji left the ballroom and the appreciative crowd behind, he commented, “This is no place for a brahmacārī.”

| | Mientras Svāmīji dejaba el salón de baile y la agradecida multitud detrás, comentó: “Este no es lugar para un brahmacārī".

|  | The next morning the temple was crowded with young people who had seen Svāmīji at the Avalon. Most of them had stayed up all night. Śrīla Prabhupāda, having followed his usual morning schedule, came down at seven, held kīrtana, and delivered the morning lecture.

| | A la mañana siguiente, el templo estaba lleno de gente joven que había visto a Svāmīji en el Avalon. La mayoría de ellos se habían quedado despiertos toda la noche. Śrīla Prabhupāda, siguió su horario matutino habitual, bajó a las siete, realizó kīrtana y dio la conferencia matutina.

|  | Later that morning, while riding to the beach with Kīrtanānanda and Hayagrīva, Svāmīji asked how many people had attended last night’s kīrtana. When they told him, he asked how much money they had made, and they said they weren’t sure but it was approximately fifteen hundred dollars.

| | Más tarde esa mañana, mientras viajaba a la playa con Kīrtanānanda y Hayagrīva, Svāmīji preguntó cuántas personas habían asistido al kīrtana de anoche. Cuando le dijeron, les preguntó cuánto dinero habían ganado, dijeron que no estaban seguros pero que eran aproximadamente mil quinientos dólares.

|  | Half-audibly he chanted in the back seat of the car, looking out the window as quiet and unassuming as a child, with no indication that the night before he had been cheered and applauded by thousands of hippies, who had stood back and made a grand aisle for him to walk in triumph across the strobe-lit floor amid the thunder of the electric basses and pounding drums of the Avalon Ballroom. For all the fanfare of the night before, he remained untouched, the same as ever in personal demeanor: he was aloof, innocent, and humble, while at the same time appearing very grave and ancient. As Kīrtanānanda and Hayagrīva were aware, Svāmīji was not of this world. They knew that he, unlike them, was always thinking of Kṛṣṇa.

| | Cantó medio audiblemente en el asiento trasero del coche, mirando por la ventana tan silencioso y sin pretensiones como un niño, sin ningún indicio de que la noche anterior había sido vitoreado y aplaudido por miles de hippies, que habían retrocedido y hecho gran pasillo para que él caminara triunfante por el piso iluminado con luz estroboscópica en medio del trueno de los bajos eléctricos y los tambores del Salón Avalon. A pesar de toda la fanfarria de la noche anterior, permaneció intacto, igual que siempre en su comportamiento personal: era distante, inocente y humilde, mientras que al mismo tiempo parecía muy grave y anciano. Como sabían Kīrtanānanda y Hayagrīva, Svāmīji no era de este mundo. Sabían que él, a diferencia de ellos, siempre estaba pensando en Kṛṣṇa.

|  | They walked with him along the boardwalk, near the ocean, with its cool breezes and cresting waves. Kīrtanānanda spread the cādara over Prabhupāda’s shoulders. “In Bengali there is one nice verse,” Prabhupāda remarked, breaking his silence. “I remember. ‘Oh, what is that voice across the sea calling, calling: Come here, come here. …’ ” Speaking little, he walked the boardwalk with his two friends, frequently looking out at the sea and sky. As he walked he softly sang a mantra that Kīrtanānanda and Hayagrīva had never heard before: “Govinda jaya jaya, gopāla jaya jaya, rādhā-ramaṇa hari, govinda jaya jaya.” He sang slowly, in a deep voice, as they walked along the boardwalk. He looked out at the Pacific Ocean: “Because it is great, it is tranquil.”

| | Caminaron con él por el malecón, cerca del océano, con su brisa fresca y sus olas crecientes. Kīrtanānanda extendió el cādara sobre los hombros de Prabhupāda. “En bengalí hay un bonito verso”, comentó Prabhupāda, rompiendo su silencio. “Recuerdo. “Oh, ¿qué es esa voz al otro lado del mar que llama, llama: Ven aquí, ven aquí? ...’” Hablando poco, caminó por el paseo marítimo con sus dos amigos, con frecuencia mirando al mar y al cielo. Mientras caminaba, cantó suavemente un mantra que Kīrtanānanda y Hayagrīva nunca habían escuchado antes: “Govinda jaya jaya, gopāla jaya jaya, rādhā-ramaṇa hari, govinda jaya jaya". Cantó lentamente, con voz profunda, mientras caminaban por el malecón. Miró al Océano Pacífico: “Porque es genial, es tranquilo".

|  | “The ocean seems to be eternal,” Hayagrīva ventured.

| | “El océano parece ser eterno”, aventuró Hayagrīva.

|  | “No,” Prabhupāda replied. “Nothing in the material world is eternal.”

| | “No”, respondió Prabhupāda. “Nada en el mundo material es eterno".

|  | In New York, since there were so few women present at the temple, people had inquired whether it were possible for a woman to join the Kṛṣṇa consciousness movement. But in San Francisco that question never arose. Most of the men who came to learn from Svāmīji came with their girlfriends. To Prabhupāda these boys and girls, eager for chanting and hearing about Kṛṣṇa, were like sparks of faith to be fanned into steady, blazing fires of devotional life. There was no question of his asking the newcomers to give up their girlfriends or boyfriends, and yet he uncompromisingly preached, “no illicit sex.” The dilemma, however, seemed to have an obvious solution: marry the couples in Kṛṣṇa consciousness.

| | En Nueva York, dado que había tan pocas mujeres presentes en el templo, la gente había preguntado si era posible que una mujer se uniera al movimiento para la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa. Pero en San Francisco esa pregunta nunca surgió. La mayoría de los hombres que vinieron a aprender de Svāmīji vinieron con sus novias. Para Prabhupāda, estos jóvenes, ansiosos por cantar y escuchar acerca de Kṛṣṇa, eran como chispas de fe que se avivaban en fuegos ardientes y constantes de vida devocional. No cabía duda de que pedía a los recién llegados que renunciaran a sus novias o novios, predicaba sin concesiones: “nada de sexo ilícito". Sin embargo, el dilema parecía tener una solución obvia: casarse con las parejas con Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa.

|  | Because traditionally a sannyāsī would never arrange or perform marriages, by Indian standards someone might criticize Prabhupāda for allowing any mingling of the sexes. But Prabhupāda gave priority to spreading Kṛṣṇa consciousness. What Indian, however critical, had ever tried to transplant the essence of India’s spiritual culture into the Western culture? Prabhupāda saw that to change the American social system and completely separate the men from the women would not be possible. But to compromise his standard of no illicit sex was also not possible. Therefore, Kṛṣṇa conscious married life, the gṛhastha-āśrama, would be the best arrangement for many of his new aspiring disciples. In Kṛṣṇa consciousness husband and wife could live together and help one another in spiritual progress. It was an authorized arrangement for allowing a man and woman to associate. If as spiritual master he found it necessary to perform marriages himself, he would do it. But first these young couples would have to become attracted to Kṛṣṇa consciousness.

| | Debido a que tradicionalmente un sannyāsī nunca arreglaba ni realizaba matrimonios, según los estándares indios, alguien podría criticar a Prabhupāda por permitir cualquier mezcla de sexos. Pero Prabhupāda dio prioridad a difundir la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa. ¿Qué indio, por crítico que fuera, había intentado alguna vez trasplantar la esencia de la cultura espiritual de la India a la cultura occidental? Prabhupāda vio que cambiar el sistema social estadounidense y separar completamente a los hombres de las mujeres no sería posible. Pero tampoco era posible comprometer su estándar de no tener relaciones sexuales ilícitas. Por lo tanto, la vida matrimonial en Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa, el gṛhastha-āśrama, sería el mejor arreglo para muchos de sus nuevos aspirantes a discípulos. Con Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa, el esposo y la esposa pueden vivir juntos y ayudarse mutuamente en el progreso espiritual. Era un arreglo autorizado para permitir que un hombre y una mujer se asociaran. Si, como maestro espiritual, consideraba necesario realizar él mismo los matrimonios, lo haría. Pero primero estas parejas jóvenes tendrían que sentirse atraídas por la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa.

|  | Joan Campanella had grown up in a wealthy suburb of Portland, Oregon, where her father was a corporate tax attorney. She and her sister had had their own sports cars and their own boats for sailing on Lake Oswego. Disgusted by the sorority life at the University of Oregon, Joan had dropped out during her first term and enrolled at Reed College, where she had studied ceramics, weaving, and calligraphy. In 1963, she had moved to San Francisco and become the co-owner of a ceramics shop. Although she had then had many friends among fashionable shopkeepers, folksingers, and dancers, she had remained aloof and introspective.

| | Joan Campanella había crecido en un rico suburbio de Portland, Oregon, donde su padre era abogado de impuestos corporativos. Ella y su hermana tenían sus propios autos deportivos y sus propios botes para navegar en el lago Oswego. Disgustada por la vida de la hermandad de mujeres en la Universidad de Oregon, Joan abandonó durante su primer período y se matriculó en el Colegio Reed, donde estudió cerámica, tejido y caligrafía. En 1963, se mudó a San Francisco y se convirtió en copropietaria de una tienda de cerámica. Aunque entonces tuvo muchos amigos entre comerciantes de moda, cantantes populares y bailarines, se había mantenido distante e introspectiva.

|  | It was through her sister Jan that Joan had first met Śrīla Prabhupāda. Jan had gone with her boyfriend Michael Grant to live in New York City, where Michael had worked as a music arranger. In 1965 they had met Svāmīji while he was living alone on the Bowery, and they had become his initiated disciples (Mukunda and Jānakī). Svāmīji had asked them to get married, and they had invited Joan to the wedding. As a wedding guest for one day, Joan had then briefly entered Svāmīji’s transcendental world at 26 Second Avenue, and he had kept her busy all day making dough and filling kacaurī pastries for the wedding feast. Joan had worked in one room, and Svāmīji had worked in the kitchen, although he had repeatedly come in and guided her in making the kacaurīs properly, telling her not to touch her clothes or body while cooking and instructing her not to smoke cigarettes, because the food was to be offered to Lord Kṛṣṇa and therefore had to be prepared purely. Joan had been convinced by this brief association that Svāmīji was a great spiritual teacher, but she had returned to San Francisco without pursuing Kṛṣṇa consciousness further.