|

Śrīla Prabhupāda Līlambṛta - — Śrīla Prabhupāda Līlambṛta

Volume 2 — Planting The Seed — Volumen 2 — Plantando la semilla

<< 20 Stay High Forever >> — << 20 Mantente elevado por siempre >>

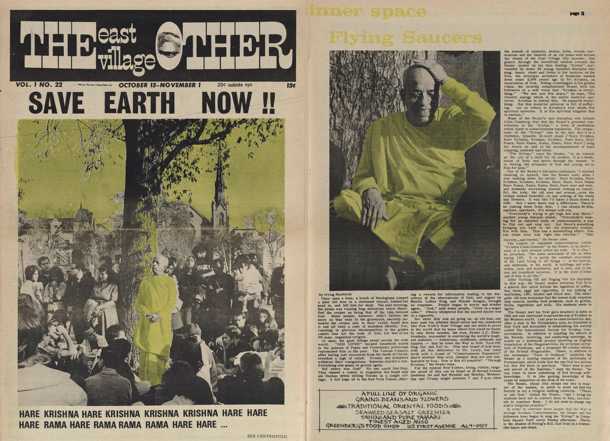

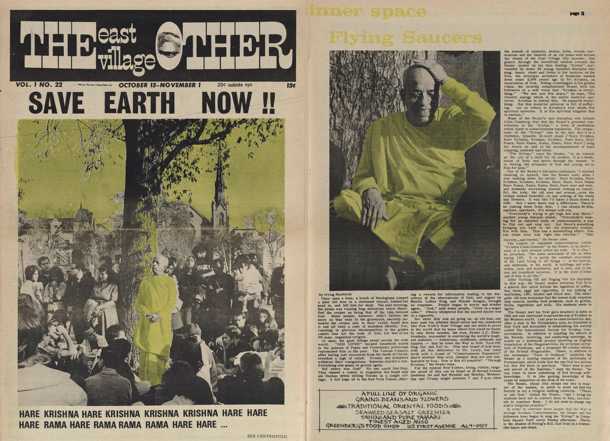

| “But while this was going on, an old man, one year past his allotted three score and ten, wandered into New York’s East Village and set about to prove to the world that he knew where God could be found. In only three months, the man, Svāmī A. C. Bhaktivedanta, succeeded in convincing the world’s toughest audience – Bohemians, acidheads, potheads, and hippies – that he knew the way to God: Turn Off, Sing Out, and Fall In. This new brand of holy man, with all due deference to Dr. Leary, has come forth with a brand of “Consciousness Expansion” that’s sweeter than acid, cheaper than pot, and nonbustible by fuzz. How is all this possible? “Through Kṛṣṇa,” the Svāmī says.”

— from The East Village Other, October 1966

| | «Pero mientras esto sucedía, un anciano, un año después de su puntaje asignado de tres y diez, entró en el Barrio Este de Nueva York y se dispuso a demostrarle al mundo que sabía dónde se podía encontrar a Dios. En solo tres meses, el hombre, Svāmī A. C. Bhaktivedanta, logró convencer a la audiencia más dura del mundo: bohemios, cabezudos, mariguannos e hippies, que conocía el camino hacia Dios: apague, cante y ríndete. Este nuevo tipo de hombre santo, con toda la debida deferencia hacia el Dr. Leary, ha presentado una marca de. “Expansión de la conciencia.” que es más dulce que el ácido, más barato que la marihuana y la policía no la puede quemar. ¿Cómo es todo esto posible? “A través de Kṛṣṇa", dice el Svāmī».

— de The East Village Other, Octubre de 1966

|  | PRABHUPĀDA’S HEALTH WAS good that summer and fall, or so it seemed. He worked long and hard, and except for four hours of rest at night, he was always active. He would speak intensively on and on, never tiring, and his voice was strong. His smiles were strong and charming; his singing voice loud and melodious. During kīrtana he would thump Bengali mṛdaṅga rhythms on his bongo drum, sometimes for an hour. He ate heartily of rice, dāl, capātīs, and vegetables with ghī. His face was full and his belly protuberant. Sometimes, in a light mood, he would drum with two fingers on his belly and say that the resonance affirmed his good health. His golden color had the radiance of youth and well-being preserved by seventy years of healthy, nondestructive habits. When he smiled, virility and vitality came on so strong as to embarrass a faded, dissolute New Yorker. In many ways, he was not at all like an old man. And his new followers completely accepted his active youthfulness as a part of the wonder of Svāmīji, just as they had come to accept the wonder of the chanting and the wonder of Kṛṣṇa. Svāmīji wasn’t an ordinary man. He was spiritual. He could do anything. None of his followers dared advise him to slow down, nor did it ever really occur to them that he needed such protection – they were busy just trying to keep up with him.

| | LA SALUD DE PRABHUPĀDA FUE BUENA ese verano y otoño, o eso parecía. Trabajó mucho y duro, y salvo cuatro horas de descanso por la noche, siempre estuvo activo. Hablaba intensamente una y otra vez, nunca se cansaba, su voz era fuerte. Sus sonrisas eran fuertes y encantadoras; su voz cantando fuerte y melodiosa. Durante el kīrtana golpeaba ritmos bengalíes de mṛdaṅga en su tambor bongo, a veces durante una hora. Comió arroz, dāl, capātīs y vegetales con mantequilla. Su rostro estaba lleno y su barriga protuberante. A veces, de buen humor, tocaba el tambor con dos dedos sobre su vientre y decía que la resonancia afirmaba su buena salud. Su color dorado tenía el resplandor de la juventud y el bienestar preservado por setenta años de hábitos saludables y no destructivos. Cuando sonrió, la virilidad y la vitalidad se hicieron tan fuertes que avergonzaron a un neoyorquino desvaído y disoluto. En muchos sentidos, no se parecía en nada a un anciano. Sus nuevos seguidores aceptaron completamente su juventud activa como parte de la maravilla de Svāmīji, tal como habían llegado a aceptar la maravilla del canto y la maravilla de Kṛṣṇa. Svāmīji no era un hombre común. Él era espiritual. Él podía hacer cualquier cosa. Ninguno de sus seguidores se atrevió a aconsejarle que redujera la velocidad, ni se les ocurrió realmente que necesitaba tal protección: estaban ocupados tratando de seguirle el ritmo.

|  | During the two months at 26 Second Avenue, he had achieved what had formerly been only a dream. He now had a temple, a duly registered society, full freedom to preach, and a band of initiated disciples. When a Godbrother had written asking him how he would manage a temple in New York, Prabhupāda had said that he would need men from India but that he might find an American or two who could help. That had been last winter. Now Kṛṣṇa had put him in a different situation: he had received no help from his Godbrothers, no big donations from Indian business magnates, and no assistance from the Indian government, but he was finding success in a different way. These were “happy days,” he said. He had struggled alone for a year, but then “Kṛṣṇa sent me men and money.”

| | Durante los dos meses en el 26 de la Segunda Avenida, había logrado lo que antes había sido solo un sueño. Ahora tenía un templo, una sociedad debidamente registrada, plena libertad para predicar y una banda de discípulos iniciados. Cuando un hermano espiritual escribió preguntándole cómo manejaría un templo en Nueva York, Prabhupāda dijo que necesitaría hombres de la India, pero que podría encontrar uno o dos estadounidenses que pudieran ayudarlo. Eso había sido el invierno pasado. Ahora Kṛṣṇa lo había puesto en una situación diferente: no recibió ayuda de sus hermanos espirituales, ni grandes donaciones de magnates de negocios indios, ni asistencia del gobierno indio, pero estaba obteniendo éxito de una manera diferente. Estos fueron. “días felices", dijo. Luchó solo durante un año, pero luego. “Kṛṣṇa me envió hombres y dinero".

|  | Yes, these were happy days for Prabhupāda, but his happiness was not like the happiness of an old man’s “sunset years,” as he fades into the dim comforts of retirement. His was the happiness of youth, a time of blossoming, of new powers, a time when future hopes expand without limit. He was seventy-one years old, but in ambition he was a courageous youth. He was like a young giant just beginning to grow. He was happy because his preaching was taking hold, just as Lord Caitanya had been happy when He had traveled alone to South India, spreading the chanting of Hare Kṛṣṇa. Prabhupāda’s happiness was that of a selfless servant of Kṛṣṇa to whom Kṛṣṇa was sending candidates for devotional life. He was happy to place the seed of devotion within their hearts and to train them in chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa, hearing about Kṛṣṇa, and working to spread Kṛṣṇa consciousness.

| | Sí, estos fueron días felices para Prabhupāda, pero su felicidad no era como la felicidad de los. “años del ocaso.” de un anciano, ya que se desvanece en las tenues comodidades de la jubilación. La suya fue la felicidad de la juventud, una época de florecimiento, de nuevos poderes, una época en que las esperanzas futuras se expanden sin límites. Tenía setenta y un años, pero su ambición era la de un joven valiente. Era como un joven gigante que apenas comenzaba a crecer. Estaba feliz porque su prédica lo estaba apoderando, tal como el Señor Caitanya estuvo feliz cuando viajó solo al sur de la India, difundiendo el canto de Hare Kṛṣṇa. La felicidad de Prabhupāda era la de un sirviente desinteresado de Kṛṣṇa a quien Kṛṣṇa estaba enviando candidatos para la vida devocional. Estaba feliz de colocar la semilla de la devoción dentro de sus corazones y entrenarlos para cantar Hare Kṛṣṇa, escuchar acerca de Kṛṣṇa y trabajar para difundir la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa.

|  | Prabhupāda continued to accelerate. After the first initiations and the first marriage, he was eager for the next step. He was pleased by what he had, but he wanted to do more. It was the greed of the Vaiṣṇava – not a greed to have sense gratification but to take more and more for Kṛṣṇa. He would “go in like a needle and come out like a plow.” That is to say, from a small, seemingly insignificant beginning, he would expand his movement to tremendous proportions. At least, that was his desire. He was not content with his newfound success and security at 26 Second Avenue, but was yearning to increase ISKCON as far as possible. This had always been his vision, and he had written it into the ISKCON charter: “to achieve real unity and peace in the world … within the members, and humanity at large.”

| | Prabhupāda continuó acelerando. Después de las primeras iniciaciones y el primer matrimonio, estaba ansioso por el siguiente paso. Estaba contento con lo que tenía, pero quería hacer más. Era la avaricia de los vaiṣṇavas, no una avaricia por tener la complacencia de los sentidos, sino por dar cada vez más por Kṛṣṇa. Él. “entraba como una aguja y salía como un arado". Es decir, desde un comienzo pequeño, aparentemente insignificante, expandiría su movimiento a proporciones tremendas. Al menos, ese era su deseo. No estaba contento con su nuevo éxito y seguridad en el 26 de la Segunda Avenida, pero ansiaba aumentar ISKCON en la medida de lo posible. Esta siempre había sido su visión y la había escrito en la carta de ISKCON: “para lograr la verdadera unidad y paz en el mundo ... dentro de los miembros y la humanidad en general".

|  | Svāmīji gathered his group together. He knew that once they tried it they would love it. But it would only happen if he personally went with them. Washington Square Park was only half a mile away, maybe a little more.

| | Svāmīji reunió a su grupo. Sabía que una vez que lo intentaran, les encantaría. Pero solo sucedería si él personalmente iba con ellos. El Parque de la Plaza de Washington estaba a 1 kilómetro de distancia, tal vez un poco más.

|  | Ravīndra-svarūpa: He never made a secret of what he was doing. He used to say, “I want everybody to know what we are doing.” Then one day, D-day came. He said, “We are going to chant in Washington Square Park.” Everybody was scared. You just don’t go into a park and chant. It seemed like a weird thing to do. But he assured us, saying, “You won’t be afraid when you start chanting. Kṛṣṇa will help you.” And so we trudged down to Washington Square Park, but we were very upset about it. Up until that time, we weren’t exposing ourselves. I was upset about it, and I know that several other people were, to be making a public figure of yourself.

| | Ravīndra-svarūpa: Él nunca ocultó lo que estaba haciendo. Solía decir: “Quiero que todos sepan lo que estamos haciendo". Entonces, un día, llegó el día D. Dijo: “Vamos a cantar en el Parque de la Plaza de Washington". Todos estaban asustados. No vas simplemente a un parque y cantas. Parecía una cosa rara de hacer. Pero nos aseguró, diciendo: “No tendrán miedo cuando comiencen a cantar. Kṛṣṇa les ayudará”. Entonces caminamos penosamente hasta el Parque de la Plaza de Washington, pero estábamos muy molestos por eso. Hasta ese momento, no nos estábamos exponiendo. Estaba molesto por eso y sé que muchas otras personas se iban a hacer una figura pública de ti mismo.

|  | With Prabhupāda leading they set out on that fair Sunday morning, walking the city blocks from Second Avenue to Washington Square in the heart of Greenwich Village. And the way he looked – just by walking he created a sensation. None of the boys had shaved heads or robes, but because of Svāmīji – with his saffron robes, his white pointy shoes, and his shaved head held high – people were astonished. It wasn’t like when he would go out alone. That brought nothing more than an occasional second glance. But today, with a group of young men hurrying to keep up with him as he headed through the city streets, obviously about to do something, he caused a stir. Tough guys and kids called out names, and others laughed and made sounds. A year ago, in Butler, the Agarwals had been sure that Prabhupāda had not come to America for followers. “He didn’t want to make any waves,” Sally had thought. But now he was making waves, walking through the New York City streets, headed for the first public chanting in America, followed by his first disciples.

| | Con Prabhupāda a la cabeza partieron en esa feria el domingo por la mañana, caminando las cuadras de la ciudad desde la Segunda Avenida hasta el Parque de la Plaza de Washington en el corazón del Pueblo de Greenwich. Y la forma en que se veía, con solo caminar, creó una sensación. Ninguno de los muchachos se había afeitado la cabeza traía túnica, pero debido al Svāmīji, con su túnica de azafrán, sus zapatos blancos puntiagudos y su cabeza afeitada en alto, la gente estaba asombrada. No era como cuando saldía solo. Eso no trajo nada más que una segunda mirada ocasional. Pero hoy, con un grupo de jóvenes apresurándose para seguirle el ritmo mientras se dirigía por las calles de la ciudad, obviamente a punto de hacer algo, causó revuelo. Los chicos y chicos rudos gritaban nombres, otros se reían y emitían sonidos. Hace un año, en el Butler, los Agarwals estaban seguros de que Prabhupāda no había venido a Norteamérica en busca de seguidores. “No quería hacer olas", había pensado Sally. Pero ahora estaba haciendo olas, caminando por las calles de la ciudad de Nueva York, dirigiéndose al primer canto público en Norteamérica, seguido por sus primeros discípulos.

|  | In the park there were hundreds of people milling about – stylish, decadent Greenwich Villagers, visitors from other boroughs, tourists from other states and other lands – an amalgam of faces, nationalities, ages, and interests. As usual, someone was playing his guitar by the fountain, boys and girls were sitting together and kissing, some were throwing Frisbees, some were playing drums or flutes or other instruments, and some were walking their dogs, talking, watching everything, wandering around. It was a typical day in the Village.

| | En el parque había cientos de personas dando vueltas: vecinos de Greenwich elegantes y decadentes, visitantes de otros municipios, turistas de otros estados y otras tierras, una amalgama de rostros, nacionalidades, edades e intereses. Como de costumbre, alguien tocaba su guitarra junto a la fuente, niños y niñas se sentaban juntos y se besaban, algunos lanzaban frisbees, otros tocaban tambores o flautas u otros instrumentos y algunos paseaban a sus perros, hablaban, miraban todo, deambulaban. Era un día típico en el pueblo.

|  | Prabhupāda went to a patch of lawn where, despite a small sign that read Keep Off the Grass, many people were lounging. He sat down, and one by one his followers sat beside him. He took out his brass hand cymbals and sang the mahā-mantra, and his disciples responded, awkwardly at first, then stronger. It wasn’t as bad as they had thought it would be.

| | Prabhupāda fue a una mancha de césped donde, a pesar de un pequeño letrero que decía Mantengase alejado del pasto, muchas personas estaban descansando. Se sentó, uno por uno sus seguidores se sentaron a su lado. Sacó sus platillos de mano de latón y cantó el mahā-mantra y sus discípulos respondieron, torpemente al principio, luego más fuerte. No fue tan malo como habían pensado que sería.

|  | Jagannātha: It was a marvelous thing, a marvelous experience that Svāmīji brought upon me. Because it opened me up a great deal, and I overcame a certain shyness – the first time to chant out in the middle of everything.

| | Jagannātha: Fue una cosa maravillosa, una experiencia maravillosa que Svāmīji me trajo. Porque me abrió mucho y superé cierta timidez, la primera vez que cantaba en medio de todo.

|  | A curious crowd gathered to watch, though no one joined in. Within a few minutes, two policemen moved in through the crowd. “Who’s in charge here?” an officer asked roughly. The boys looked toward Prabhupāda. “Didn’t you see the sign?” an officer asked. Svāmīji furrowed his brow and turned his eyes toward the sign. He got up and walked to the uncomfortably warm pavement and sat down again, and his followers straggled after to sit around him. Prabhupāda continued the chanting for half an hour, and the crowd stood listening. A guru in America had never gone onto the streets before and sung the names of God.

| | Una multitud curiosa se reunió para mirar, aunque nadie se unió. En unos minutos, dos policías entraron a través de la multitud. “¿Quién está a cargo aquí?.” preguntó un oficial con rudeza. Los muchachos miraron hacia Prabhupāda. “¿No viste el letrero?.” preguntó un oficial. Svāmīji frunció el ceño y volvió los ojos hacia el letrero. Se levantó y caminó hacia el pavimento incómodamente cálido y volvió a sentarse, sus seguidores se tambalearon para sentarse a su alrededor. Prabhupāda continuó el canto durante media hora y la multitud permaneció escuchando. Un guru en Estados Unidos nunca antes había salido a la calle a cantar los nombres de Dios.

|  | After kīrtana, he asked for a copy of the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam and had Hayagrīva read aloud from the preface. With clear articulation, Hayagrīva read: “Disparity in the human society is due to the basic principle of a godless civilization. There is God, the Almighty One, from whom everything emanates, by whom everything is maintained, and in whom everything is merged to rest. …” The crowd was still. Afterward, the Svāmī and his followers walked back to the storefront, feeling elated and victorious. They had broken the American silence.

| | Después del kīrtana, pidió una copia del Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam e hizo que Hayagrīva leyera en voz alta del prefacio. Con una articulación clara, Hayagrīva leyó: “La disparidad en la sociedad humana se debe al principio básico de una civilización impía. Está Dios, el Todopoderoso, de quien todo emana, por quien todo se mantiene y en quien todo se fusiona para descansar... “La multitud estaba quieta. Después, el Svāmī y sus seguidores regresaron a la tienda, sintiéndose eufóricos y victoriosos. Se había roto el silencio Norteamericano.

|  | Allen Ginsberg lived nearby on East Tenth Street. One day he received a peculiar invitation in the mail:

| | Allen Ginsberg vivía cerca, en la calle 10 Este. Un día recibió una invitación peculiar por correo:

|  | “Practice the transcendental sound vibration,

Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa, Hare Hare

Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare.

This chanting will cleanse the dust from the mirror of the mind.

International Society for Kṛṣṇa Consciousness

Meetings at 7 A.M. daily

Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays at 7:00 P.M.

You are cordially invited to come and bring your friends.”

| | «Practica la vibración del sonido trascendental,

Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa, Hare Hare

Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare.

Este canto limpiará el polvo del espejo de la mente.

Sociedad Internacional para la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa br>

Reuniones a las 7 a.m. diariamente

Lunes, miércoles y viernes a las 7:00 p.m.

Estás cordialmente invitado a venir y traer a tus amigos».

|  | Svāmīji had asked the boys to distribute it around the neighborhood.

| | Svāmīji les había pedido a los jóvenes que lo distribuyeran por el vecindario.

|  | One evening, soon after he received the invitation, Allen Ginsberg and his roommate, Peter Orlovsky, arrived at the storefront in a Volkswagen minibus. Allen had been captivated by the Hare Kṛṣṇa mantra several years before, when he had first encountered it at the Kumbha-melā festival in Allahabad, India, and he had been chanting it often ever since. The devotees were impressed to see the world-famous author of Howl and leading figure of the beat generation enter their humble storefront. His advocation of free sex, marijuana, and LSD, his claims of drug-induced visions of spirituality in everyday sights, his political ideas, his exploration of insanity, revolt, and nakedness, and his attempts to create a harmony of likeminded souls – all were influential on the minds of American young people, especially those living on the Lower East Side. Although by middle-class standards he was scandalous and disheveled, he was, in his own right, a figure of worldly repute, more so than anyone who had ever come to the storefront before.

| | Una tarde, poco después de recibir la invitación, Allen Ginsberg y su compañero de cuarto, Peter Orlovsky, llegaron a la tienda en un minibús de Volkswagen. Allen había sido cautivado por el mantra Hare Kṛṣṇa varios años antes, cuando lo encontró por primera vez en el festival Kumbha-melā en Allahabad, India y lo había estado cantando a menudo desde entonces. Los devotos quedaron impresionados al ver al famoso autor mundial de Howl y la figura principal de la generación beat entrar en su humilde escaparate. Su defensa del sexo libre, la marihuana y el LSD, sus afirmaciones de visiones de espiritualidad inducidas por las drogas en los paisajes cotidianos, sus ideas políticas, su exploración de la locura, la revuelta, la desnudez, sus intentos de crear una armonía de almas de ideas afines, todo influyeron en las mentes de los jóvenes estadounidenses, especialmente aquellos que viven en el Lado Este Bajo. Aunque para los estándares de la clase media era escandaloso y desaliñado, era, por derecho propio, una figura de fama mundial, más que cualquiera que hubiera visitado la tienda antes.

|  | Allen Ginsberg: Bhaktivedanta seemed to have no friends in America, but was alone, totally alone, and gone somewhat like a lone hippie to the nearest refuge, the place where it was cheap enough to rent.

| | Allen Ginsberg: Bhaktivedanta parecía no tener amigos en Estados Unidos, estaba solo, totalmente solo, fue como un hippie solitario al refugio más cercano, el lugar donde era lo suficientemente barato como para poder alquilar.

|  | There were a few people sitting cross-legged on the floor. I think most of them were Lower East Side hippies who had just wandered in off the street, with beards and a curiosity and inquisitiveness and a respect for spiritual presentation of some kind. Some of them were sitting there with glazed eyes, but most of them were just like gentle folk – bearded, hip, and curious. They were refugees from the middle class in the Lower East Side, looking exactly like the street sādhus in India. It was very similar, that phase in American underground history. And I liked immediately the idea that Svāmī Bhaktivedanta had chosen the Lower East Side of New York for his practice. He’d gone to the lower depths. He’d gone to a spot more like the side streets of Calcutta than any other place.

| | Había algunas personas sentadas con las piernas cruzadas en el suelo. Creo que la mayoría de ellos eran hippies del Lado Este Bajo que acababan de salir de la calle, con barba, curiosos, inquisitivos y con respeto por una presentación espiritual de algún tipo. Algunos de ellos estaban sentados allí con los ojos vidriosos, pero la mayoría de ellos eran gentiles, barbudos, modernos y curiosos. Eran refugiados de la clase media en el Lado Este Bajo, que se veían exactamente como los sādhus de la calle en la India. Fue muy similar, esa fase en la historia underground estadounidense. Y me gustó de inmediato la idea de que Svāmī Bhaktivedanta había elegido el Lado Este Bajo de Nueva York para su práctica. Se había ido a las profundidades más bajas. Había ido a un lugar más parecido a las calles laterales de Calcuta que a cualquier otro lugar.

|  | Allen and Peter had come for the kīrtana, but it wasn’t quite time – Prabhupāda hadn’t come down. They presented a new harmonium to the devotees. “It’s for the kīrtanas,” said Allen. “A little donation.” Allen stood at the entrance to the storefront, talking with Hayagrīva, telling him how he had been chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa around the world – at peace marches, poetry readings, a procession in Prague, a writers’ union in Moscow. “Secular kīrtana,” said Allen, “but Hare Kṛṣṇa nonetheless.” Then Prabhupāda entered. Allen and Peter sat with the congregation and joined in the kīrtana. Allen played harmonium.

| | Allen y Peter fueron por el kīrtana, pero aún no era el momento: Prabhupāda no había bajado. Presentaron un nuevo armonio a los devotos. “Es para los kīrtanas", dijo Allen. “Una pequeña donación". Allen se paró en la entrada de la tienda, hablando con Hayagrīva, diciéndole cómo había estado cantando Hare Kṛṣṇa en todo el mundo: en marchas de paz, lecturas de poesía, una procesión en Praga, un sindicato de escritores en Moscú. “Kīrtana secular", dijo Allen,. “pero Hare Kṛṣṇa no obstante". Entonces entró Prabhupāda. Allen y Peter se sentaron con la congregación y se unieron al kīrtana. Allen tocó el armonio.

|  | Allen: I was astounded that he’d come with the chanting, because it seemed like a reinforcement from India. I had been running around singing Hare Kṛṣṇa but had never understood exactly why or what it meant. But I was surprised to see that he had a different melody, because I thought the melody I knew was the melody, the universal melody. I had gotten so used to my melody that actually the biggest difference I had with him was over the tune – because I’d solidified it in my mind for years, and to hear another tune actually blew my mind.

| | Allen: Me sorprendió que viniera con el canto, porque parecía un refuerzo de la India. Había estado corriendo cantando Hare Kṛṣṇa pero nunca había entendido exactamente por qué o qué significaba. Me sorprendió ver que tenía una melodía diferente, porque pensé que la melodía que conocía era la melodía, la melodía universal. Me había acostumbrado tanto a mi melodía que, en realidad, la mayor diferencia que tuve con él fue la melodía, porque lo había solidificado en mi mente durante años y escuchar otra melodía realmente me voló la cabeza.

|  | After the lecture, Allen came forward to meet Prabhupāda, who was still sitting on his dais. Allen offered his respects with folded palms and touched Prabhupāda’s feet, and Prabhupāda reciprocated by nodding his head and folding his palms. They talked together briefly, and then Prabhupāda returned to his apartment. Allen mentioned to Hayagrīva that he would like to come by again and talk more with Prabhupāda, so Hayagrīva invited him to come the next day and stay for lunch prasādam.

| | Después de la conferencia, Allen se adelantó para encontrarse con Prabhupāda, que todavía estaba sentado en su tarima. Allen ofreció sus respetos con las palmas dobladas y tocó los pies de Prabhupāda, Prabhupāda correspondió asintiendo con la cabeza y juntando las palmas. Hablaron juntos brevemente, luego Prabhupāda regresó a su departamento. Allen le mencionó a Hayagrīva que le gustaría volver y hablar más con Prabhupāda, así que Hayagrīva lo invitó a venir al día siguiente y quedarse a almorzar prasādam.

|  | Don’t you think Svāmīji is a little too esoteric for New York?” Allen asked. Hayagrīva thought. “Maybe,” he replied.

| | '¿No crees que Svāmīji es demasiado esotérico para Nueva York?' Preguntó Allen. Hayagrīva pensó y respondió 'tal vez'.

|  | Hayagrīva then asked Allen to help the Svāmī, since his visa would soon expire. He had entered the country with a visa for a two-month stay, and he had been extending his visa for two more months again and again. This had gone on for one year, but the last time he had applied for an extension, he had been refused. “We need an immigration lawyer,” said Hayagrīva. “I’ll donate to that,” Allen assured him.

| | Hayagrīva luego le pidió a Allen que ayudara al Svāmī, ya que su visa pronto expiraría. Ingresó al país con una visa para una estadía de dos meses, la h estado extendiendo por dos meses más una y otra vez. Esto ya llevaba un año, pero la última vez que solicitó una extensión, se le negó. “Necesitamos un abogado de inmigración", dijo Hayagrīva. “Voy a donar para eso", le aseguró Allen.

|  | The next morning, Allen Ginsberg came by with a check and another harmonium. Up in Prabhupāda’s apartment, he demonstrated his melody for chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa, and then he and Prabhupāda talked.

| | A la mañana siguiente, llegó Allen Ginsberg con un cheque y otro armonio. En el departamento de Prabhupāda, demostró su melodía para cantar Hare Kṛṣṇa, y luego él y Prabhupāda hablaron.

|  | Allen: I was a little shy with him because I didn’t know where he was coming from. I had that harmonium I wanted to donate, and I had a little money. I thought it was great now that he was here to expound on the Hare Kṛṣṇa mantra – that would sort of justify my singing. I knew what I was doing, but I didn’t have any theological background to satisfy further inquiries, and here was someone who did. So I thought that was absolutely great. Now I could go around singing Hare Kṛṣṇa, and if anybody wanted to know what it was, I could just send them to Svāmī Bhaktivedanta to find out. If anyone wanted to know the technical intricacies and the ultimate history, I could send them to him.

| | Allen: Fui un poco tímido con él porque no sabía de dónde venía. Tenía ese armonio que quería donar y tenía un poco de dinero. Pensé que era genial ahora que él estaba aquí para exponer el mantra Hare Kṛṣṇa, eso podría justificar mi canto. Sabía lo que estaba haciendo, pero no tenía ningún fondo teológico para satisfacer más consultas, aquí había alguien que sí. Entonces pensé que eso era absolutamente genial. Ahora podría ir cantando Hare Kṛṣṇa y si alguien quisiera saber de qué se trata, podría enviarlo a Svāmī Bhaktivedanta para que lo averigue. Si alguien quere conocer las complejidades técnicas y la historia definitiva, podía enviárselos.

|  | He explained to me about his own teacher and about Caitanya and the lineage going back. His head was filled with so many things and what he was doing. He was already working on his translations. He always seemed to be sitting there just day after day and night after night. And I think he had one or two people helping him.

| | Me explicó sobre su propio maestro y sobre Caitanya y sobreel linaje del que viene. Su cabeza estaba llena de tantas cosas, lo que estaba haciendo. Estaba trabajando en sus traducciones. Siempre estaba sentado allí solo día tras día y noche tras noche. Creo que tenía una o dos personas ayudándolo.

|  | Prabhupāda was very cordial with Allen. Quoting a passage from Bhagavad-gītā where Kṛṣṇa says that whatever a great man does, others will follow, he requested Allen to continue chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa at every opportunity, so that others would follow his example. He told about Lord Caitanya’s organizing the first civil disobedience movement in India, leading a saṅkīrtana protest march against the Muslim ruler. Allen was fascinated. He enjoyed talking with the Svāmī.

| | Prabhupāda fue muy cordial con Allen. Citando un pasaje del Bhagavad-gītā donde Kṛṣṇa dice que haga lo que haga un gran hombre, que otros lo seguirán, le pidió a Allen que continúe cantando Hare Kṛṣṇa en cada oportunidad, para que otros sigan su ejemplo. Le contó que el Señor Caitanya organizó el primer movimiento de desobediencia civil en India, liderando una marcha de protesta saṅkīrtana contra un gobernante musulmán. Allen estaba fascinado. Le gustaba hablar con el Svāmī.

|  | But they had their differences. When Allen expressed his admiration for a well-known Bengali holy man, Prabhupāda said that the holy man was bogus. Allen was shocked. He’d never before heard a swami severely criticize another’s practice. Prabhupāda explained, on the basis of Vedic evidence, the reasoning behind his criticism, and Allen admitted that he had naively thought that all holy men were one-hundred-percent holy. But now he decided that he should not simply accept a sādhu, including Prabhupāda, on blind faith. He decided to see Prabhupāda in a more severe, critical light.

| | Pero tenían sus diferencias. Cuando Allen expresó su admiración por un conocido hombre santo bengalí, Prabhupāda dijo que ese hombre santo era falso. Allen se sorprendió. Nunca antes había escuchado a un swami criticar severamente la práctica de otro. Prabhupāda le explicó, basándose en la evidencia védica, el razonamiento detrás de sus críticas y Allen admitió que ingenuamente había pensado que todos los hombres santos eran cien por ciento santos. Pero ahora decidió que no debía simplemente aceptar a un sādhu con fe ciega, incluyendo a Prabhupāda. Decidió ver a Prabhupāda en una luz más severa y crítica.

|  | Allen: I had a very superstitious attitude of respect, which probably was an idiot sense of mentality, and so Svāmī Bhaktivedanta’s teaching was very good to make me question that. It also made me question him and not take him for granted.

| | Allen: Tenía una actitud de respeto muy supersticiosa, que probablemente era una mentalidad en un sentido idiota, por lo que la enseñanza de Svāmī Bhaktivedanta fue muy buena para hacerme cuestionar eso. También me hizo cuestionarlo a él y no darlo por sentado.

|  | Allen described a divine vision he’d had in which William Blake had appeared to him in sound, and in which he had understood the oneness of all things. A sādhu in Vṛndāvana had told Allen that this meant that William Blake was his guru. But to Prabhupāda this made no sense.

| | Allen describió una visión divina que había tenido en la que William Blake se le había aparecido en el sonido, en el que había entendido la unidad de todas las cosas. Un sādhu en Vṛndāvana le dijo a Allen que esto significaba que William Blake era su guru. Pero para Prabhupāda esto no tenía sentido.

|  | Allen: The main thing, above and beyond all our differences, was an aroma of sweetness that he had, a personal, selfless sweetness like total devotion. And that was what always conquered me, whatever intellectual questions or doubts I had, or even cynical views of ego. In his presence there was a kind of personal charm, coming from dedication, that conquered all our conflicts. Even though I didn’t agree with him, I always liked to be with him.

| | Allen: Lo principal, más allá de todas nuestras diferencias, era un aroma de dulzura que tenía, una dulzura personal y desinteresada como la devoción total. Eso fue lo que siempre me conquistó, cualesquiera que fueran las preguntas o dudas intelectuales que tenía, o incluso las opiniones cínicas del ego. En su presencia había una especie de encanto personal, proveniente de la dedicación, que conquistó todos nuestros conflictos. Aunque no estaba de acuerdo con él, siempre me gustó estar con él.

|  | Allen agreed, at Prabhupāda’s request, to chant more and to try to give up smoking.

| | Allen aceptó, a pedido de Prabhupāda, cantar más y tratar de dejar de fumar.

|  | ““Do you really intend to make these American boys into Vaiṣṇavas?” Allen asked.

“Yes,” Prabhupāda replied happily, “and I will make them all brāhmaṇas.”

| | «“'¿Realmente pretendes convertir a estos niños estadounidenses en vaiṣṇavas?' Preguntó Allen.

'Sí', respondió felizmente Prabhupāda, 'los haré a todos brāhmaṇas'».

|  | Allen left a $200 check to help cover the legal expenses for extending the Svāmī’s visa and wished him good luck. “Brāhmaṇas!” Allen didn’t see how such a transformation could be possible.

| | Allen dejó un cheque de $200 para ayudar a cubrir los gastos legales para extender la visa del Svāmī y le deseó buena suerte. “¡Brāhmaṇas!.” Allen no veía cómo tal transformación podría ser posible.

|  | September 23

| | 23 de Septiembre

|  | It was Rādhāṣṭamī, the appearance day of Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī, Lord Kṛṣṇa’s eternal consort. Prabhupāda held his second initiation. Keith became Kīrtanānanda, Steve became Satsvarūpa, Bruce became Brahmānanda, and Chuck became Acyutānanda. It was another festive day with a fire sacrifice in Prabhupāda’s front room and a big feast.

| | Era Rādhāṣṭamī, el día de la aparición de Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī, la consorte eterna del Señor Kṛṣṇa. Prabhupāda celebró su segunda iniciación. Keith se convirtió en Kīrtanānanda, Steve se convirtió en Satsvarūpa, Bruce se convirtió en Brahmānanda y Chuck se convirtió en Acyutānanda. Fue otro día festivo con un sacrificio de fuego en la habitación de Prabhupāda y una gran fiesta.

|  | Prabhupāda lived amid the drug culture, in a neighborhood where the young people were almost desperately attempting to alter their consciousness, whether by drugs or by some other means – whatever was available. Prabhupāda assured them that they could easily achieve the higher consciousness they desired by chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa. It was inevitable that in explaining Kṛṣṇa consciousness he would make allusions to the drug experience, even if only to show that the two were contrary paths. He was familiar already with Indian “sādhus” who took gāñjā and hashish on the plea of aiding their meditations. And even before he had left India, hippie tourists had become a familiar sight on the streets of Delhi.

| | Prabhupāda vivía en medio de la cultura de las drogas, en un vecindario donde los jóvenes intentaban casi desesperadamente alterar su conciencia, ya sea por drogas o por algún otro medio, lo que estuviera disponible. Prabhupāda les aseguró que podrían lograr fácilmente la conciencia superior que deseaban cantando Hare Kṛṣṇa. Era inevitable que al explicar la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa hiciera alusiones a la experiencia de las drogas, aunque solo fuera para mostrar que los dos eran caminos contrarios. Ya estaba familiarizado con los. “sādhus.” indios que tomaron gāñjā y hachís con el pretexto de ayudar a sus meditaciones. E incluso antes de salir de la India, los turistas hippies se habían convertido en un espectáculo familiar en las calles de Delhi.

|  | The hippies liked India because of the cultural mystique and easy access to drugs. They would meet their Indian counterparts, who assured them that taking hashish was spiritual, and then they would return to America and perpetrate their misconceptions of Indian spiritual culture.

| | A los hippies les gustaba la India debido a la mística cultural y al fácil acceso a las drogas. Se encontraban con sus contrapartes indias, quienes les aseguraron que tomar hachís era espiritual, luego regresarían a Norteamérica y perpetuarían sus ideas erróneas sobre la cultura espiritual india.

|  | It was the way of life. The local head shops carried a full line of paraphernalia. Marijuana, LSD, peyote, cocaine, and hard drugs like heroin and barbiturates were easily purchased on the streets and in the parks. Underground newspapers reported important news on the drug scene, featured a cartoon character named Captain High, and ran crossword puzzles that only a seasoned “head” could answer.

| | Era una forma de vida. Las principales tiendas locales ofrecían una línea completa de parafernalia. La marihuana, el LSD, el peyote, la cocaína y las drogas duras como la heroína y los barbitúricos se compraban fácilmente en las calles y en los parques. Los periódicos subterráneos informaron noticias importantes sobre la escena del narcotráfico, presentaron un personaje de dibujos animados llamado Capitán High y ejecutaron crucigramas que solo una. “cabeza.” experimentada podía responder.

|  | Prabhupāda had to teach that Kṛṣṇa consciousness was beyond the revered LSD trip. “Do you think taking LSD can produce ecstasy and higher consciousness?” he once asked his storefront audience. “Then just imagine a roomful of LSD. Kṛṣṇa consciousness is like that.” People would regularly come in and ask Svāmīji’s disciples, “Do you get high from this?” And the devotees would answer, “Oh, yes. You can get high just by chanting. Why don’t you try it?”

| | Prabhupāda tuvo que enseñar que la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa estaba más allá del venerado viaje de LSD. “¿Crees que tomar LSD puede producir éxtasis y una mayor conciencia?.” una vez le preguntó a su público de la tienda. “Entonces imagina una habitación llena de LSD. La Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa es así". La gente entraba regularmente y preguntaba a los discípulos del Svāmīji: “¿Te drogas con esto?.” Y los devotos respondían: “Oh, sí. Puedes drogarte solo cantando. ¿Por qué no lo intentas?"

|  | Greg Scharf (Brahmānanda’s brother) hadn’t tried LSD; but he wanted higher consciousness, so he decided to try the chanting.

| | Greg Scharf (hermano de Brahmānanda) no había probado el LSD; pero quería una mayor conciencia, así que decidió intentar el canto.

|  | Greg: I was eighteen. Everyone at the storefront had taken LSD, and I thought maybe I should too, because I wanted to feel like part of the crowd. So I asked Umāpati, “Hey, Umāpati, do you think I should try LSD? Because I don’t know what you guys are talking about.” He said no, that Svāmīji said you didn’t need LSD. I never did take it, so I guess it was OK.

| | Greg: Tenía dieciocho años. Todos en la tienda habían tomado LSD, pensé que tal vez yo también debería hacerlo porque quería sentirme parte de la multitud. Entonces le pregunté a Umāpati: “Oye, Umāpati, ¿crees que debería probar el LSD? Porque no sé de qué están hablando". Dijo que no, que Svāmīji dijo que no necesitabas LSD. Nunca lo tomé, así que supongo que estuvo bien.

|  | “Hayagrīva: Have you ever heard of LSD? It’s a psychedelic drug that comes like a pill, and if you take it you can get religious ecstasies. Do you think this can help my spiritual life?

Prabhupāda: You don’t need to take anything for your spiritual life. Your spiritual life is already here.“

| | «“Hayagrīva: ¿Alguna vez has oído hablar del LSD? Es una droga psicodélica que viene en una píldora, si la tomas puedes obtener éxtasis religiosos. ¿Crees que esto puede ayudar a mi vida espiritual?

Prabhupāda: No necesitas llevar nada para tu vida espiritual. Tu vida espiritual ya está aquí».

|  | Had anyone else said such a thing, Hayagrīva would never have agreed with him. But because Svāmīji seemed “so absolutely positive,” therefore “there was no question of not agreeing.”

| | Si alguien más hubiera dicho algo así, Hayagrīva nunca hubiera estado de acuerdo con él. Pero debido a que Svāmīji parecía. “tan absolutamente positivo", por lo tanto,. “no había duda de no estar de acuerdo".

|  | Satsvarūpa: I knew Svāmīji was in a state of exalted consciousness, and I was hoping that somehow he could teach the process to me. In the privacy of his room, I asked him, “Is there spiritual advancement that you can make from which you won’t fall back?” By his answer – “Yes” – I was convinced that my own attempts to be spiritual on LSD, only to fall down later, could be replaced by a total spiritual life such as Svāmīji had. I could see he was convinced, and then I was convinced.

| | Satsvarūpa: Sabía que el Svāmīji estaba en un estado de conciencia exaltada, esperaba que de alguna manera él me pudiera enseñar el proceso. En la privacidad de su habitación, le pregunté: “¿Hay algún avance espiritual que puedas hacer del que no retrocederás?.” Por su respuesta,. “Sí", estaba convencido de que mis propios intentos de ser espiritual con LSD, solo para caer más tarde, podrían ser reemplazados por una vida espiritual total como la que tuvo Svāmīji. Pude ver que él estaba convencido, entonces yo también estaba convencido.

|  | Greg: LSD was like the spiritual drug of the times, and Svāmīji was the only one who dared to speak out against it, saying it was nonsense. I think that was the first battle he had to conquer in trying to promote his movement on the Lower East Side. Even those who came regularly to the storefront thought that LSD was good.

| | Greg: El LSD era como la droga espiritual de la época, Svāmīji fue el único que se atrevió a hablar en contra de eso, diciendo que no tenía sentido. Creo que esa fue la primera batalla que tuvo que conquistar para tratar de promover su movimiento en el Lado Este Bajo. Incluso aquellos que acudían regularmente a la tienda pensaban que el LSD era bueno.

|  | Probably the most famous experiments with LSD in those days were by Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert, Harvard psychology instructors who studied the effects of the drug, published their findings in professional journals, and advocated the use of LSD for self-realization and fulfillment. After being fired from Harvard, Timothy Leary went on to become a national priest of LSD and for some time ran an LSD commune in Millbrook, New York.

| | Probablemente los experimentos más famosos con LSD en esos días fueron realizados por Timothy Leary y Richard Alpert, instructores de psicología de Harvard que estudiaron los efectos de la droga, publicaron sus hallazgos en revistas especializadas y abogaron por el uso de LSD para la autorrealización y la realización. Después de ser despedido de Harvard, Timothy Leary se convirtió en el sacerdote nacional del LSD y durante algún tiempo dirigió una comuna de LSD en Millbrook, Nueva York.

|  | When the members of the Millbrook commune heard about the swami on the Lower East Side who led his followers in a chant that got you high, they began visiting the storefront. One night, a group of about ten hippies from Millbrook came to Svāmīji’s kīrtana. They all chanted (not so much in worship of Kṛṣṇa as to see what kind of high the chanting could produce), and after the lecture a Millbrook leader asked about drugs. Prabhupāda replied that drugs were not necessary for spiritual life, that they could not produce spiritual consciousness, and that all drug-induced religious visions were simply hallucinations. To realize God was not so easy or cheap that one could do it just by taking a pill or smoking. Chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa, he explained, was a purifying process to uncover one’s pure consciousness. Taking drugs would increase the covering and bar one from self-realization.

| | Cuando los miembros de la comuna de Millbrook se enteraron del swami en el Lado Este Bajo que dirigía a sus seguidores en un canto que los llevaba a lo alto, comenzaron a visitar la tienda. Una noche, un grupo de unos diez hippies de Millbrook llegó al kīrtana de Svāmīji. Todos cantaron (no tanto en adoración a Kṛṣṇa como para ver qué clase de altura podría producir el canto), después de la conferencia, un líder de Millbrook preguntó sobre las drogas. Prabhupāda respondió que las drogas no eran necesarias para la vida espiritual, que no podían producir conciencia espiritual, que todas las visiones religiosas inducidas por drogas eran simplemente alucinaciones. Darse cuenta de que Dios no era tan fácil o barato que uno podía hacerlo simplemente tomando una píldora o fumando. Cantar Hare Kṛṣṇa, explicó, fue un proceso de purificación para descubrir la conciencia pura. Tomar drogas aumentaría el tapón y evitaría la autorrealización.

|  | “'But have you ever taken LSD?' The question now became a challenge.

'No,' Prabhupāda replied. 'I have never taken any of these things, not even cigarettes or tea.'“

| | «“'¿Pero alguna vez has tomado LSD?' La pregunta ahora se convirtió en un desafío.

'No', respondió Prabhupāda. 'Nunca he tomado ninguna de estas cosas, ni siquiera cigarrillos o té'».

|  | “If you haven’t taken it, then how can you say what it is?” The Millbrookers looked around, smiling. Two or three even burst out with laughter, and they snapped their fingers, thinking the Svāmī had been checkmated.

| | "Si no lo ha tomado, ¿cómo puedes decir qué es?.” Los Millbrookers miraron a su alrededor, sonriendo. Dos o tres incluso se echaron a reír y chasquearon los dedos, pensando que el Svāmī había sido haqueado.

|  | “I have not taken,” Prabhupāda replied regally from his dais. “But my disciples have taken all these things – marijuana, LSD – many times, and they have given them all up. You can hear from them. Hayagrīva, you can speak.” And Hayagrīva sat up a little and spoke out in his stentorian best.

| | "No he tomado", respondió Prabhupāda regiamente desde su tarima. “Pero mis discípulos han tomado todas estas cosas, marihuana, LSD, muchas veces y las han abandonado. Puedes escuchar de ellos. Hayagrīva, puedes hablar. Hayagrīva se acomodó un poco y habló en su emocionada mejor forma.

|  | “Well, no matter how high you go on LSD, you eventually reach a peak, and then you have to come back down. Just like traveling into outer space in a rocket ship. [He gave one of Svāmīji’s familiar examples.] Your spacecraft can travel very far away from the earth for thousands of miles, day after day, but it cannot simply go on traveling and traveling. Eventually it must land. On LSD, we experience going up, but we always have to come down again. That’s not spiritual consciousness. When you actually attain spiritual or Kṛṣṇa consciousness, you stay high. Because you go to Kṛṣṇa, you don’t have to come down. You can stay high forever.“

| | «“Bueno, no importa qué tan alto llegues con el LSD, eventualmente alcanzas un pico y luego tienes que volver a bajar. Es como viajar al espacio exterior en un cohete. [Dio uno de los ejemplos familiares del Svāmīji.] Tu nave espacial puede viajar muy lejos de la tierra durante miles de kilómetros, día tras día, pero no puedes simplemente seguir viajando y viajando. Finalmente debes aterrizar. Con el LSD experimentamos un aumento, pero siempre tenemos que bajar nuevamente. Eso no es conciencia espiritual. Cuando realmente alcanzas la conciencia espiritual o de Kṛṣṇa, te mantienes elevado. Cuando vas a Kṛṣṇa, no tienes que bajar. Puedes mantenerte elevado por siempre».

|  | Prabhupāda was sitting in his back room with Hayagrīva and Umāpati and other disciples. The evening meeting had just ended, and the visitors from Millbrook had gone. “Kṛṣṇa consciousness is so nice, Svāmīji,” Umāpati spoke up. “You just get higher and higher, and you don’t come down.”

| | Prabhupāda estaba sentado en su habitación trasera con Hayagrīva, Umāpati y otros discípulos. La reunión de la tarde acababa de terminar y los visitantes de Millbrook se habían ido. “La Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa es muy agradable, Svāmīji", dijo Umāpati. “Simplemente te posicionas más y más alto y no bajas".

|  | Prabhupāda smiled. “Yes, that’s right.”

| | Prabhupāda sonrió. “Sí, así es".

|  | “No more coming down,” Umāpati said, laughing, and the others also began to laugh. Some clapped their hands, repeating, “No more coming down.”

| | “No bajes más”, dijo Umāpati, riendo; los demás también comenzaron a reír. Algunos aplaudieron, repitiendo: “No más bajones".

|  | The conversation inspired Hayagrīva and Umāpati to produce a new handbill:

| | La conversación inspiró a Hayagrīva y Umāpati a producir un nuevo folleto:

|  | “STAY HIGH FOREVER!

No More Coming Down

Practice Kṛṣṇa Consciousness

Expand your Consciousness by practicing the

* TRANSCENDENTAL SOUND VIBRATION *

HARE KRISHNA HARE KRISHNA KRISHNA KRISHNA HARE HARE

HARE RAMA HARE RAMA RAMA RAMA HARE HARE“

| | «“MANTENTE ELEVADO POR SIEMPRE!

No más bajones

Practica la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa

Expande tu conciencia practicando la

*VIBRACIÓN DEL SONIDO TRANSCENDENTAL*

HARE KRISHNA HARE KRISHNA KRISHNA KRISHNA HARE HARE

HARE RAMA HARE RAMA RAMA RAMA HARE HARE»

|  | The leaflet went on to extol Kṛṣṇa consciousness over any other high. It included phrases like “end all bringdowns” and “turn on,” and it spoke against “employing artificially induced methods of self-realization and expanded consciousness.” Someone objected to the flyer’s “playing too much off the hippie mentality,” but Prabhupāda said it was all right.

| | El folleto continuó exaltando la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa por encima de cualquier otra cosa. Incluía frases como. “pon fin a todos los bajones.” y. “enciéndete", habló en contra de. “emplear métodos artificialmente inducidos de autorrealización y conciencia expandida". Alguien se opuso a que el volante. “jugara demasiado con la mentalidad hippie", pero Prabhupāda dijo que estaba bien.

|  | Greg: When these drug people on the Lower East Side came and talked to Svāmīji, he was so patient with them. He was speaking on a philosophy which they had never heard before. When someone takes LSD, they’re really into themselves, and they don’t hear properly when someone talks to them. So Svāmīji would make particular points, and they wouldn’t understand him. So he would have to make the same point again. He was very patient with these people, but he would not give in to their claim that LSD was a bona fide spiritual aid to self-realization.

| | Greg: Cuando las personas del narcotráfico en el Lado Este Bajo vinieron y hablaron con el Svāmīji, él fue muy paciente con ellos. Estaba hablando de una filosofía que nunca habían escuchado antes. Cuando alguien toma LSD, está realmente metido en sí mismo y no escucha correctamente cuando alguien habla con él. Entonces Svāmīji haría puntos particulares, no lo entendían. Entonces tendría que hacer lo mismo otra vez. Fue muy paciente con estas personas, pero no cedió a la afirmación de ellos de que el LSD era una ayuda espiritual genuina para la autorrealización.

|  | October 1966

| | Octubre de 1966

|  | Tompkins Square Park was the park on the Lower East Side. On the south, it was bordered by Seventh Street, with its four- and five-storied brownstone tenements. On the north side was Tenth, with more brownstones, but in better condition, and the very old, small building that housed the Tompkins Square branch of the New York Public Library. On Avenue B, the park’s east border, stood St. Brigid’s Church, built in 1848, when the neighborhood had been entirely Irish. The church, school, and rectory still occupied much of the block. And the west border of the park, Avenue A, was lined with tiny old candy stores selling newspapers, magazines, cigarettes, and egg-creme sodas at the counter. There were also a few bars, several grocery stores, and a couple of Slavic restaurants specializing in inexpensive vegetable broths, which brought Ukranians and hippies side by side for bodily nourishment.

| | Tompkins Square Park era el parque en el Lado Este Bajo. En el sur, estaba bordeada por la calle 7, con sus viviendas de piedra rojiza de cuatro y cinco pisos. En el lado norte estaba la calle 10, con más piedras marrones, pero en mejores condiciones, y el muy pequeño y antiguo edificio que albergaba la sucursal de Parque Tompkins de la Biblioteca Pública de Nueva York. En la avenida B, la frontera este del parque, se encontraba la iglesia de Santa Brigid, construida en 1848, cuando el vecindario era completamente irlandés. La iglesia, la escuela y la rectoría todavía ocupaban gran parte del bloque. Y la frontera oeste del parque, la avenida A, estaba llena de pequeñas tiendas de dulces que vendían periódicos, revistas, cigarrillos y refrescos con crema de huevo en el mostrador. También había algunos bares, varias tiendas de comestibles y un par de restaurantes eslavos que se especializaban en caldos de verduras económicos, que llevaban a los ucranianos y los hippies de lado a lado para la nutrición corporal.

|  | The park’s ten acres held many tall trees, but at least half the park was paved. A network of five-foot-high heavy wrought-iron fences weaved through the park, lining the walkways and protecting the grass. The fences and the many walkways and entrances to the park gave it the effect of a maze.

| | Las 4 hectáreas del parque contenían muchos árboles altos, pero al menos la mitad del parque estaba pavimentado. Una red de pesadas vallas de hierro forjado de metro y medio de alto se tejió a través del parque, bordeando los pasillos y protegiendo la hierba. Las cercas y las numerosas pasarelas y entradas al parque le dieron el efecto de un laberinto.

|  | Since the weather was still warm and it was Sunday, the park was crowded with people. Almost all the space on the benches that lined the walkways was occupied. There were old people, mostly Ukranians, dressed in outdated suits and sweaters, even in the warm weather, sitting together in clans, talking. There were many children in the park also, mostly Puerto Ricans and blacks but also fair-haired, hard-faced slum kids racing around on bikes or playing with balls and Frisbees. The basketball and handball courts were mostly taken by the teenagers. And as always, there were plenty of loose, running dogs.

| | Como el clima aún era cálido y era domingo, el parque estaba lleno de gente. Casi todo el espacio en los bancos que bordeaban los pasillos estaba ocupado. Había ancianos, en su mayoría ucranianos, vestidos con trajes y suéteres anticuados, incluso en el clima cálido, sentados juntos en clanes, hablando. También había muchos niños en el parque, en su mayoría portorriqueños y negros, pero también había niños de tugurios rubios y de cara dura que corrían en bicicleta o jugaban con pelotas y frisbees. Las canchas de baloncesto y balonmano fueron ocupadas principalmente por los adolescentes. Y como siempre, había muchos perros sueltos corriendo.

|  | A marble miniature gazebo (four pillars and a roof, with a drinking fountain inside) was a remnant from the old days – 1891, according to the inscription. On its four sides were the words HOPE, FAITH, CHARITY, and TEMPERANCE. But someone had sprayed the whole structure with black paint, making crude designs and illegible names and initials. Today, a bench had been taken over by several conga and bongo drummers, and the whole park pulsed with their demanding rhythms.

| | Un cenador en miniatura de mármol (cuatro pilares y un techo, con una fuente para beber dentro) era un remanente de los viejos tiempos, 1891, según la inscripción. En sus cuatro lados estaban las palabras ESPERANZA, FE, CARIDAD Y TEMPERANCIA. Pero alguien había rociado toda la estructura con pintura negra, haciendo diseños burdos y nombres e iniciales ilegibles. Hoy, varios bancos de conga y bongo habían tomado el banco, y todo el parque latía con sus exigentes ritmos.

|  | And the hippies were there, different from the others. The bearded Bohemian men and their long-haired young girlfriends dressed in old blue jeans were still an unusual sight. Even in the Lower East Side melting pot, their presence created tension. They were from middle-class families, and so they had not been driven to the slums by dire economic necessity. This created conflicts in their dealings with the underprivileged immigrants. And the hippies’ well-known proclivity for psychedelic drugs, their revolt against their families and affluence, and their absorption in the avant-garde sometimes made them the jeered minority among their neighbors. But the hippies just wanted to do their own thing and create their own revolution for “love and peace,” so usually they were tolerated, although not appreciated.

| | Y los hippies estaban allí, diferentes de los demás. Los hombres bohemios barbudos y sus novias jóvenes de pelo largo vestidas con viejos jeans azules todavía eran una vista inusual. Incluso en el crisol del Lado Este Bajo, su presencia creó tensión. Eran de familias de clase media, por lo que no habían sido conducidos a los barrios bajos por una grave necesidad económica. Esto creó conflictos en sus tratos con los inmigrantes desfavorecidos. Y la conocida propensión de los hippies a las drogas psicodélicas, su rebelión contra sus familias, su riqueza, y su absorción en la vanguardia a veces los convertía en la minoría burlada entre sus vecinos. Pero los hippies solo querían hacer lo suyo y crear su propia revolución para el. “amor y la paz", por lo que generalmente eran tolerados, aunque no apreciados.

|  | There were various groups among the young and hip at Tompkins Square Park. There were friends who had gone to the same school together, who took the same drug together, or who agreed on a particular philosophy of art, literature, politics, or metaphysics. There were lovers. There were groups hanging out together for reasons undecipherable, except for the common purpose of doing their own thing. And there were others, who lived like hermits – a loner would sit on a park bench, analyzing the effects of cocaine, looking up at the strangely rustling green leaves of the trees and the blue sky above the tenements and then down to the garbage at his feet, as he helplessly followed his mind from fear to illumination, to disgust to hallucination, on and on, until after a few hours the drug began to wear off and he was again a common stranger. Sometimes they would sit up all night, “spaced out” in the park, until at last, in the light of morning, they would stretch out on benches to sleep.

| | Había varios grupos entre jóvenes y modernos en el Jardín del Parque Tompkins. Había amigos que asistieron juntos a la misma escuela, que tomaban la misma droga juntos o que estaban de acuerdo con una filosofía particular de arte, literatura, política o metafísica. Grupos que se juntaban por razones indescifrables, excepto por el propósito común de hacer lo suyo. Y otros, que vivían como ermitaños: un solitario se sentaba en un banco del parque, analizaba los efectos de la cocaína, miraba las hojas verdes de los árboles y el cielo azul sobre las viviendas y luego bajaba a la basura. sus pies, mientras seguía impotente su mente desde el miedo hasta la iluminación, desde el asco hasta la alucinación, hasta que, después de unas pocas horas, la droga comenzó a desaparecer y volvió a ser un extraño común. A veces se quedaban sentados toda la noche,. “espaciados.” en el parque, hasta que por fin, a la luz de la mañana, se estiraban en bancos para dormir.

|  | Hippies especially took to the park on Sundays. They at least passed through the park on their way to St. Mark’s Place, Greenwich Village, or the Lexington Avenue subway at Astor Place, or the IND subway at Houston and Second, or to catch an uptown bus on First Avenue, a downtown bus on Second, or a crosstown on Ninth. Or they went to the park just to get out of their apartments and sit together in the open air – to get high again, to talk, or to walk through the park’s maze of pathways.

| | Los hippies especialmente iban al parque los domingos. Al menos pasaron por el parque camino a la Plaza de San Maros, el pueblo de Greenwich, o el metro de la avenida Lexington en la plaza Astor, o el metro de IND en Houston y la segunda, o para tomar un autobús en la parte alta de la primera avenida, un autobús del centro en el segundo, o una ciudad cruzada en el noveno. O fueron al parque solo para salir de sus apartamentos y sentarse juntos al aire libre, para drogarse nuevamente, hablar o caminar por el laberinto de caminos del parque.

|  | But whatever the hippies’ diverse interests and drives, the Lower East Side was an essential part of the mystique. It was not just a dirty slum; it was the best place in the world to conduct the experiment in consciousness. For all its filth and threat of violence and the confined life of its brownstone tenements, the Lower East Side was still the forefront of the revolution in mind expansion. Unless you were living there and taking psychedelics or marijuana, or at least intellectually pursuing the quest for free personal religion, you weren’t enlightened, and you weren’t taking part in the most progressive evolution of human consciousness. And it was this searching – a quest beyond the humdrum existence of the ordinary, materialistic, “straight” American – that brought unity to the otherwise eclectic gathering of hippies on the Lower East Side.

| | Pero cualesquiera que sean los diversos intereses e impulsos de los hippies, el Lado Este Bajo era una parte esencial de la mística. No era solo un tugurio sucio; era el mejor lugar del mundo para realizar el experimento en conciencia. A pesar de toda su inmundicia y amenaza de violencia y la vida confinada de sus viviendas de piedra rojiza, el Lado Este Bajo seguía siendo la vanguardia de la revolución en expansión mental. A menos que vivieras allí y tomaras psicodélicos o marihuana, o al menos persiguieras intelectualmente la búsqueda de una religión personal libre, no estabas iluminado y no participabas en la evolución más progresiva de la conciencia humana. Y fue esta búsqueda, una búsqueda más allá de la existencia monótona del estadounidense ordinario, materialista y. “heterosexual", lo que trajo unidad a la reunión, por lo demás ecléctica, de hippies en el Lado Este Bajo.

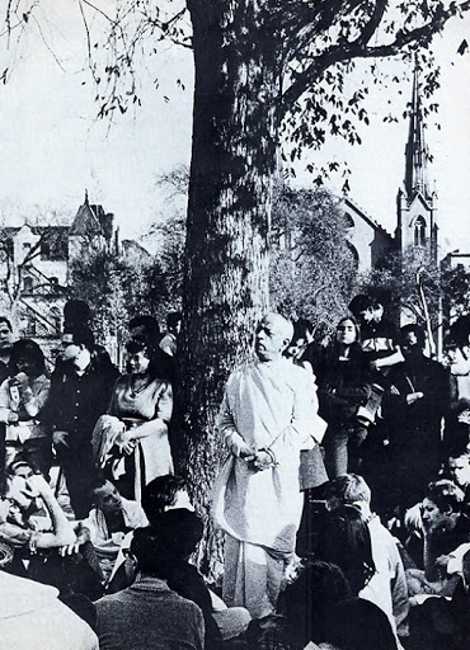

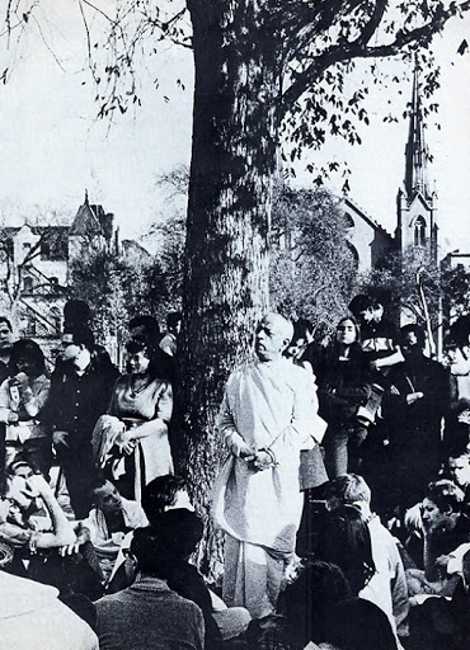

|  | Into this chaotic pageant Svāmīji entered with his followers and sat down to hold a kīrtana. Three or four devotees who arrived ahead of him selected an open area of the park, put out the Oriental carpet Robert Nelson had donated, sat down on it, and began playing karatālas and chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa. Immediately some boys rode up on their bicycles, braked just short of the carpet, and stood astride their bikes, curiously and irreverently staring. Other passersby gathered to listen.

| | En este caótico desfile, Svāmīji entró con sus seguidores y se sentó a dirigir un kīrtana. Tres o cuatro devotos que llegaron antes que él seleccionaron un área abierta del parque, colocaron la alfombra oriental que Robert Nelson había donado, se sentaron en ella y comenzaron a tocar karatālas y a cantar Hare Kṛṣṇa. Inmediatamente, algunos muchachos se subieron a sus bicicletas, frenaron poco antes de llegar a la alfombra y se pararon a horcajadas sobre sus bicicletas, mirando con curiosidad e irreverencia. Otros transeúntes se reunieron para escuchar.

|  | Meanwhile Svāmīji, accompanied by half a dozen disciples, was walking the eight blocks from the storefront. Brahmānanda carried the harmonium and the Svāmī’s drum. Kīrtanānanda, who was now shaven-headed at Svāmīji’s request and dressed in loose-flowing canary yellow robes, created an extra sensation. Drivers pulled their cars over to have a look, their passengers leaning forward, agape at the outrageous dress and shaved head. As the group passed a store, people inside would poke each other and indicate the spectacle. People came to the windows of their tenements, taking in the Svāmī and his group as if a parade were passing. The Puerto Rican tough guys, especially, couldn’t restrain themselves from exaggerated reactions. “Hey, Buddha!” they taunted. “Hey, you forgot to change your pajamas!” They made shrill screams as if imitating Indian war whoops they had heard in Hollywood westerns.

| | Mientras tanto, Svāmīji, acompañado por media docena de discípulos, caminaba las ocho cuadras desde la entrada a la tienda. Brahmānanda llevó el armonio y el tambor de Svāmī. Kīrtanānanda, que ahora tenía la cabeza rapada a pedido de Svāmīji y vestía una túnica amarilla canaria suelta, creó una sensación extra. Los conductores detuvieron sus autos para echar un vistazo, sus pasajeros se inclinaron hacia adelante, boquiabiertos ante el escandaloso vestido y la cabeza afeitada. Cuando el grupo pasaba por una tienda, las personas que estaban adentro se tocaban entre sí e indicaban el espectáculo. La gente acudía a las ventanas de sus viviendas, contemplando al Svāmī y su grupo como si estuviera pasando un desfile. Los duros puertorriqueños, especialmente, no pudieron evitar reacciones exageradas. “¡Oye, Buda!.” se burlaron. “¡Oye, olvidaste cambiarte el pijama!.” Hicieron gritos agudos como si imitaran los gritos de guerra de los indios que habían escuchado en los westerns de Hollywood.

|  | “Hey, A-rabs!” exclaimed one heckler, who began imitating what he thought was an Eastern dance. No one on the street knew anything about Kṛṣṇa consciousness, nor even of Hindu culture and customs. To them, the Svāmī’s entourage was just a bunch of crazy hippies showing off. But they didn’t quite know what to make of the Svāmī. He was different. Nevertheless, they were suspicious. Some, however, like Irving Halpern, a veteran Lower East Side resident, felt sympathetic toward this stranger, who was “apparently a very dignified person on a peaceful mission.”

| | "¡Hey, A-rabes!.” exclamó un odioso, que empezó a imitar lo que pensaba que era una danza oriental. Nadie en la calle sabía nada sobre la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa, ni siquiera sobre la cultura y las costumbres hindúes. Para ellos, el séquito de Svāmī era solo un grupo de hippies locos presumiendo. Pero no sabían muy bien qué pensar del Svāmī. El era diferente. Sin embargo sospechaban. Algunos, sin embargo, como Irving Halpern, un veterano residente del Lado Este Bajo, se compadecieron de este extraño, que. “aparentemente era una persona muy digna en una misión pacífica".

|  | Irving Halpern: A lot of people had spectacularized notions of what a swami was. As though they were going to suddenly see people lying on little mattresses made out of nails – and all kinds of other absurd notions. Yet here came just a very graceful, peaceful, gentle, obviously well-meaning being into a lot of hostility.

| | Irving Halpern: Mucha gente tenía nociones espectacularizadas de lo que era un swami. Como si fueran a ver de repente a gente acostada en colchones hechos con clavos y todo tipo de ideas absurdas. Sin embargo, aquí vino un ser muy elegante, pacífico, gentil, obviamente bien intencionado, enmedio de mucha hostilidad.

|  | “Hippies!”

“What are they, Communists?”

| | "¡Hippies!"

"¿Qué son, comunistas?"

|  | While the young taunted, the middle-aged and elderly shook their heads or stared, cold and uncomprehending. The way to the park was spotted with blasphemies, ribald jokes, and tension, but no violence. After the successful kīrtana in Washington Square Park, Prabhupāda had regularly been sending out “parades” of three or four devotees, chanting and playing hand cymbals through the streets and sidewalks of the Lower East Side. On one occasion, they had been bombarded with water balloons and eggs, and they were sometimes faced with bullies looking for a fight. But they were never attacked – just stared at, laughed at, or shouted after.

| | Mientras los jóvenes se burlaban, los de mediana edad y ancianos negaban con la cabeza o miraban, fríos y sin comprender. El camino hacia el parque estaba salpicado de blasfemias, bromas obscenas y tensión, pero sin violencia. Después del exitoso kīrtana en el Parque Washington, Prabhupāda había estado enviando regularmente “desfiles” de tres o cuatro devotos, cantando y tocando platillos de mano por las calles y aceras del Lado Este Bajo. En una ocasión, habían sido bombardeados con globos de agua y huevos y en ocasiones se enfrentaban a matones que buscaban pelea. Pero nunca fueron atacados, solo los miraron, se rieron o después les gritaron.

|  | Today, the ethnic neighbors just assumed that Prabhupāda and his followers had come onto the streets dressed in outlandish costumes as a joke, just to turn everything topsy-turvy and cause stares and howls. They felt that their responses were only natural for any normal, respectable American slum-dweller.

| | Hoy, los vecinos étnicos simplemente asumieron que Prabhupāda y sus seguidores habían salido a las calles vestidos con trajes extravagantes como una broma, solo para poner todo patas arriba y causar miradas y aullidos. Sentían que sus respuestas eran naturales para cualquier habitante de tugurios estadounidense normal y respetable.

|  | So it was quite an adventure before the group even reached the park. Svāmīji, however, remained unaffected. “What are they saying?” he asked once or twice, and Brahmānanda explained. Prabhupāda had a way of holding his head high, his chin up, as he walked forward. It made him look aristocratic and determined. His vision was spiritual – he saw everyone as a spiritual soul and Kṛṣṇa as the controller of everything. Yet aside from that, even from a worldly point of view he was unafraid of the city’s pandemonium. After all, he was an experienced “Calcutta man.”

| | Así que fue toda una aventura antes de que el grupo llegara al parque. Sin embargo Svāmīji no se vio afectado. “¿Qué están diciendo?.” preguntó una o dos veces y Brahmānanda se lo explicó. Prabhupāda tenía una forma de mantener la cabeza en alto, la barbilla levantada, mientras caminaba hacia adelante. Le hacía parecer aristocrático y decidido. Su visión era espiritual: veía a todos como un alma espiritual y a Kṛṣṇa como el controlador de todo. Sin embargo, aparte de eso, incluso desde un punto de vista mundano, no le tenía miedo al pandemonio de la ciudad. Después de todo, era un experimentado. “hombre de Calcuta".

|  | The kīrtana had been going for about ten minutes when Svāmīji arrived. Stepping out of his white rubber slippers, just as if he were home in the temple, he sat down on the rug with his followers, who had now stopped their singing and were watching him. He wore a pink sweater, and around his shoulders a khādī wrapper. He smiled. Looking at his group, he indicated the rhythm by counting, one … two … three. Then he began clapping his hands heavily as he continued counting, “One … two … three.” The karatālas followed, at first with wrong beats, but he kept the rhythm by clapping his hands, and then they got it, clapping hands, clashing cymbals artlessly to a slow, steady beat.

| | El kīrtana había iniciado hace unos diez minutos cuando llegó Svāmīji. Quitándose sus pantuflas blancas de goma, como si estuviera en la casa en el templo, se sentó en la alfombra con sus seguidores, que ahora habían dejado de cantar y lo estaban mirando. Llevaba un suéter rosa y alrededor de los hombros una bata khādī. Sonrió. Mirando a su grupo, indicó el ritmo contando, uno... dos... tres. Luego comenzó a aplaudir fuertemente mientras continuaba contando,. “Uno... dos... tres". Los karatālas le siguieron, al principio con ritmos equivocados, pero él mantuvo el ritmo batiendo palmas, finalmente lo consiguieron, aplaudiendo, haciendo chocar los platillos con ingenio a un ritmo lento y constante.

|  | He began singing prayers that no one else knew. Vande ’haṁ śrī-guroḥ śrī-yuta-pada-kamalaṁ śrī-gurūn vaiṣṇavāṁś ca. His voice was sweet like the harmonium, rich in the nuances of Bengali melody. Sitting on the rug under a large oak tree, he sang the mysterious Sanskrit prayers. None of his followers knew any mantra but Hare Kṛṣṇa, but they knew Svāmīji. And they kept the rhythm, listening closely to him while the trucks rumbled on the street and the conga drums pulsed in the distance.

| | Comenzó a cantar oraciones que nadie más conocía. Vande ’haṁ śrī-guroḥ śrī-yuta-pada-kamalaṁ śrī-gurūn vaiṣṇavāṁś ca. Su voz era dulce como el armonio, rica en los matices de la melodía bengalí. Sentado en la alfombra debajo de un gran roble cantó las misteriosas oraciones en sánscrito. Ninguno de sus seguidores conocía ningún mantra excepto Hare Kṛṣṇa, pero conocían a Svāmīji. Y mantuvieron el ritmo, escuchándolo atentamente mientras los camiones retumbaban en la calle y los tambores de conga pulsaban a lo lejos.

|  | As he sang – śrī-rūpaṁ sāgrajātaṁ – the dogs came by, kids stared, a few mockers pointed fingers: “Hey, who is that priest, man?” But his voice was a shelter beyond the clashing dualities. His boys went on ringing cymbals while he sang alone: śrī-rādhā-kṛṣṇa-pādān.

| | Mientras cantaba - śrī-rūpaṁ sāgrajātaṁ - pasaron unos perros, unos chicos se quedaron mirando, algunos burlones lo señalaron con el dedo: “Oye hombre, ¿quién es ese sacerdote?.” Pero su voz era un refugio más allá de las dualidades enfrentadas. Sus muchachos seguían haciendo sonar los platillos mientras él cantaba solo: śrī-rādhā-kṛṣṇa-pādān.

|  | Prabhupāda sang prayers in praise of Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī’s pure conjugal love for Kṛṣṇa, the beloved of the gopīs. Each word, passed down for hundreds of years by the intimate associates of Kṛṣṇa, was saturated with deep transcendental meaning that only he understood. Saha-gaṇa-lalitā-śrī-viśākhānvitāṁś ca. They waited for him to begin Hare Kṛṣṇa, although hearing him chant was exciting enough.

| | Prabhupāda cantó las oraciones en alabanza del amor conyugal puro de Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī por Kṛṣṇa, el amado de las gopīs. Cada palabra, transmitida durante cientos de años por los asociados íntimos de Kṛṣṇa, estaba saturada de un profundo significado trascendental que solo él entendía. Saha-gaṇa-lalitā-śrī-viśākhānvitāṁś ca. Esperaron a que comenzara con Hare Kṛṣṇa, aunque escucharlo cantar era lo suficientemente emocionante.

|  | More people came – which was what Prabhupāda wanted. He wanted them chanting and dancing with him, and now his followers wanted that too. They wanted to be with him. They had tried together at the U.N., Ananda Ashram, and Washington Square. It seemed that this would be the thing they would always do – go with Svāmīji and sit and chant. He would always be with them, chanting.

| | Llegaron más personas, que era lo que Prabhupāda quería. Quería que cantaran y bailaran con él, ahora sus seguidores también querían eso. Querían estar con él. Lo habían intentado juntos en la ONU, el Ashram Ananda y el Parque Washington. Parecía que esto sería lo que siempre harían: ir con Svāmīji y sentarse y cantar. Siempre estaría con ellos, cantando.

|  | Then he began the mantra – Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa, Hare Hare / Hare Rāma, Hare Rāma, Rāma Rāma, Hare Hare. They responded, too low and muddled at first, but he returned it to them again, singing it right and triumphant. Again they responded, gaining heart, ringing karatālas and clapping hands – one … two … three, one … two … three. Again he sang it alone, and they stayed, hanging closely on each word, clapping, beating cymbals, and watching him looking back at them from his inner concentration – his old-age wisdom, his bhakti – and out of love for Svāmīji, they broke loose from their surroundings and joined him as a chanting congregation. Svāmīji played his small drum, holding its strap in his left hand, bracing the drum against his body, and with his right hand playing intricate mṛdaṅga rhythms.

| | Luego comenzó el mantra: Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa, Hare Hare / Hare Rāma, Hare Rāma, Rāma Rāma, Hare Hare. Ellos respondieron, demasiado bajo y confuso al principio, pero él lo devolvió, cantándolo bien y triunfante. Nuevamente respondieron, con el corazón, haciendo sonar karatālas y aplaudiendo - uno... dos... tres, uno... dos... tres. De nuevo lo cantó solo y se quedaron, colgando de cada palabra, aplaudiendo, tocando platillos y mirándolo, mirándolos desde su concentración interior - su sabiduría de la vejez, su bhakti - y por amor a Svāmīji, se soltaron de su entorno y se unieron a él como una congregación que cantaba. Svāmīji tocaba su pequeño tambor, sosteniendo la correa con su mano izquierda, apoyando el tambor contra su cuerpo y con su mano derecha tocando intrincados ritmos mṛdaṅga.

|  | Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa, Hare Hare / Hare Rāma, Hare Rāma, Rāma Rāma, Hare Hare. He was going strong after half an hour, repeating the mantra, carrying them with him as interested onlookers gathered in greater numbers. A few hippies sat down on the edge of the rug, copying the cross-legged sitting posture, listening, clapping, trying the chanting, and the small inner circle of Prabhupāda and his followers grew, as gradually more people joined.