|

Śrīla Prabhupāda Līlambṛta - — Śrīla Prabhupāda Līlambṛta

Volume I — A lifetime in preparation — Volumen I — Toda una vida en preparación

<< 11 The Dream Come True >> — << 11 El sueño se hace realidad >>

| “I planned that I must go to America. Generally they go to London, but I did not want to go to London. I was simply thinking how to go to New York. I was scheming, “Whether I shall go this way, through Tokyo, Japan, or that way? Which way is cheaper?” That was my proposal. And I was targeting to New York always. Sometimes I was dreaming that I have come to New York.”

— Śrīla Prabhupāda

| | «Planeaba que debía ir a Norteamérica. Generalmente van a Londres, pero yo no quería ir a Londres. Simplemente estaba pensando en cómo ir a Nueva York. Estaba planeando: “¿Si iré por este lado, por Tokio, Japón o por ese camino? ¿Qué camino es más barato? Esa fue mi propuesta. Siempre estaba apuntando a Nueva York. A veces soñaba con haber llegado a Nueva York».

— Śrīla Prabhupāda

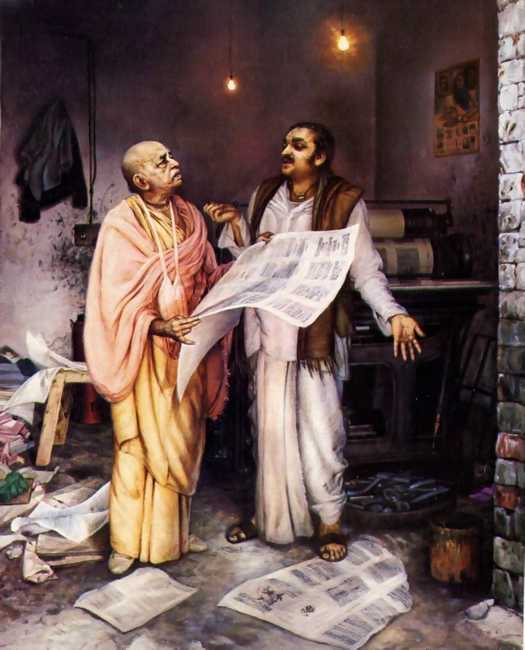

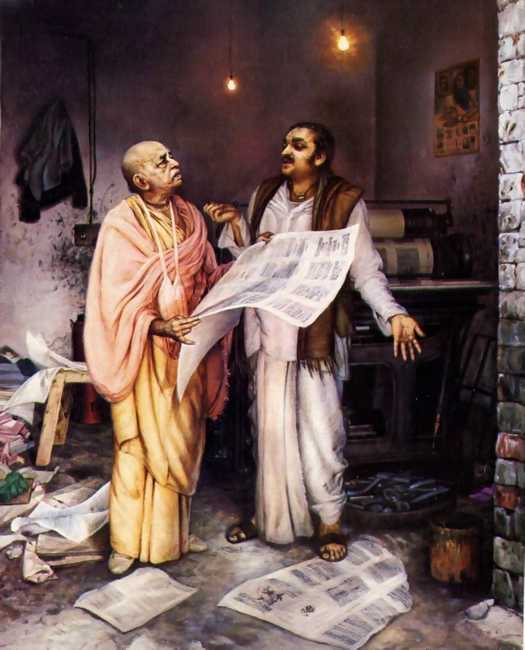

|  | WRITING WAS ONLY half the battle; the other half was publishing. Both Bhaktivedanta Svāmī and his spiritual master wanted to see Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam printed in English and distributed widely. According to the teachings of Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, the most modern methods of printing and distributing books should be used to spread Kṛṣṇa consciousness. Although many books of Vaiṣṇava wisdom had already been perfectly presented by Rūpa Gosvāmī, Sanātana Gosvāmī, and Jīva Gosvāmī, the manuscripts now sat deteriorating in the Rādhā-Dāmodara temple and other locations, and even the Gauḍīya Maṭh’s printings of the Gosvāmīs’ works were not being widely distributed. One of Bhaktivedanta Svāmī’s Godbrothers asked him why he was spending so much time and effort trying to make a new commentary on the Bhāgavatam, since so many great ācāryas had already commented upon it. But in Bhaktivedanta Svāmī’s mind there was no question; his spiritual master had given him an order.

| | ESCRIBIR ERA SOLO la mitad de la batalla; la otra mitad era publicar. Tanto Bhaktivedanta Svāmī como su maestro espiritual querían ver el Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam impreso en inglés y distribuido ampliamente. De acuerdo con las enseñanzas de Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī, los métodos más modernos de imprimir y distribuir libros deben usarse para difundir la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa. Aunque muchos libros de sabiduría vaiṣṇava ya habían sido perfectamente presentados por Rūpa Gosvāmī, Sanātana Gosvāmī y Jīva Gosvāmī, los manuscritos ahora se deterioraban en el templo Rādhā-Dāmodara y otros lugares, e incluso las impresiones del Maṭh Gauḍīya de las obras de Gosvāmīs no estaban siendo ampliamente distribuidas. Uno de los hermanos espirituales de Bhaktivedanta Svāmī le preguntó por qué estaba gastando tanto tiempo y esfuerzo tratando de hacer un nuevo comentario sobre el Bhāgavatam, ya que muchos grandes ācāryas ya lo habían comentado. Pero en la mente de Bhaktivedanta Svāmī no había duda; su maestro espiritual le había dado una orden.

|  | Commercial publishers, however, were not interested in the sixty-volume Bhāgavatam series, and Bhaktivedanta Svāmī was not interested in anything less than a sixty-volume paramparā presentation of verses, synonyms, and purports based on the commentaries of the previous ācāryas. But to publish such books he would have to raise private donations and publish at his own expense. Rādhā-Dāmodara temple may have been the best place for writing Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, but not for printing and publishing it. For that he would have to go to New Delhi.

| | Sin embargo, los editores comerciales no estaban interesados en la serie del Bhāgavatam de sesenta volúmenes y Bhaktivedanta Svāmī no estaba interesado en nada menos que una presentación paramparā de sesenta volúmenes de versos, sinónimos y significados basados en los comentarios de los ācāryas anteriores. Pero para publicar tales libros tendría que recaudar donaciones privadas y publicar a su costa. El templo Rādhā-Dāmodara puede ser el mejor lugar para escribir el Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, pero no para imprimirlo y publicarlo. Para eso tendría que ir a Nueva Delhi.

|  | Among his Delhi contacts, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī considered Hitsaran Sharma a likely helper. Although when he had stayed in Mr. Sharma’s home Mr. Sharma had appreciated him more as a member of a genre than as an individual, at least Mr. Sharma was inclined to help sādhus, and he recognized Bhaktivedanta Svāmī as a genuinely religious person. Therefore, when Bhaktivedanta Svāmī approached him in his office, he was willing to help, considering it a religious duty to propagate Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam.

| | Entre sus contactos de Delhi, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī consideraba que Hitsaran Sharma era un ayudante probable. Aunque cuando se había quedado en la casa del Sr. Sharma, el Sr. Sharma lo apreciaba más como miembro de un género que como individuo, al menos el Sr. Sharma estaba dispuesto a ayudar a sādhus y reconoció a Bhaktivedanta Svāmī como una persona verdaderamente religiosa. Por lo tanto, cuando Bhaktivedanta Svāmī se acercó en su oficina, estuvo dispuesto a ayudarlo considerando que era un deber religioso propagar el Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam.

|  | Hitsaran Sharma was qualified to help for two reasons: he was the secretary to J. D. Dalmia, a wealthy philanthropist, and he was the owner of a commercial printing works, Radha Press. According to Mr. Sharma, Mr. Dalmia would not directly give money to Bhaktivedanta Svāmī, even if his secretary suggested it. Mr. Sharma therefore advised Bhaktivedanta Svāmī to go to Gorakhpur and show his manuscript to Hanuman Prasad Poddar, a religious publisher. Accepting this as good advice, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī journeyed to Gorakhpur, some 475 miles from Delhi.

| | Hitsaran Sharma estaba calificado para ayudar por dos razones: era el secretario de J. D. Dalmia, un rico filántropo y era el dueño de una imprenta comercial, Radha Press. Según el Sr. Sharma, el Sr. Dalmia no le daría dinero directamente a Bhaktivedanta Svāmī, incluso si su secretaria lo sugiriera. Por lo tanto, el Sr. Sharma le aconsejó a Bhaktivedanta Svāmī que fuera a Gorakhpur y le mostrara su manuscrito a Hanuman Prasad Poddar, un editor religioso. Al aceptar esto como un buen consejo, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī viajó a Gorakhpur, a unos 750 kilómetros de Delhi.

|  | Even such a trip as this constituted a financial strain. Bhaktivedanta Svāmī’s daily ledger showed a balance of one hundred and thirty rupees as of August 8, 1962, the day he started for Gorakhpur. By the time he reached Lucknow he was down to fifty-seven rupees. Travel from Lucknow to Gorakhpur cost another six rupees, and the ricksha to Mr. Poddar’s home cost eighty paisa.

| | Aunque un viaje como este constituía una tensión financiera. El libro diario de Bhaktivedanta Svāmī mostró un saldo de ciento treinta rupias a partir del 8 de agosto de 1962, el día en que partió para Gorakhpur. Cuando llegó a Lucknow, había bajado a cincuenta y siete rupias. El viaje de Lucknow a Gorakhpur costó otras seis rupias y el ricksha a la casa del Sr. Poddar costó ochenta paisa.

|  | But the trip was well worth the cost. Bhaktivedanta Svāmī presented Mr. Poddar with his letter of introduction from Hitsaran Sharma and then showed him his manuscript. After briefly examining the manuscript, Mr. Poddar concluded it to be a highly developed work that should be supported. He agreed to send a donation of four thousand rupees to the Dalmia Trust in Delhi, to be used towards the publication of Śrī A. C. Bhaktivedanta Svāmī’s Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam.

| | Pero el viaje valió la pena el costo. Bhaktivedanta Svāmī presentó al Sr. Poddar su carta de presentación de Hitsaran Sharma y luego le mostró su manuscrito. Después de examinar brevemente el manuscrito, el Sr. Poddar concluyó que era un trabajo altamente desarrollado que debería ser apoyado. Estuvo de acuerdo en enviar una donación de cuatro mil rupias al Dalmia Trust en Delhi, para ser utilizada en la publicación del Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam de Śrī A. C. Bhaktivedanta Svāmī.

|  | Indian printers do not always require full payment before they begin a job, provided they receive a substantial advance payment. After the job is printed and bound, a customer who has not made the complete payment takes a portion of books commensurate to what he has paid, and after selling those books he uses his profit to buy more. Bhaktivedanta Svāmī estimated that printing one volume would cost seven thousand rupees. So he was three thousand short. He raised a few hundred rupees more by going door to door throughout Delhi. Then he went back to Radha Press and asked Hitsaran Sharma to begin. Mr. Sharma agreed.

| | Las imprentas indias no siempre requieren el pago completo antes de comenzar un trabajo, siempre que reciban un pago anticipado sustancial. Después de que el trabajo se imprime y encuaderna, un cliente que no ha realizado el pago completo toma una parte de los libros de acuerdo con lo que ha pagado y después de vender esos libros, utiliza sus ganancias para comprar más. Bhaktivedanta Svāmī estimó que imprimir un volumen costaría siete mil rupias. Entonces tenía tres mil menos. Colectó unos cientos de rupias más yendo de puerta en puerta por toda Delhi. Luego volvió a Radha Press y le pidió a Hitsaran Sharma que comenzara. El Sr. Sharma estuvo de acuerdo.

|  | Radha Press had already produced much of the first two chapters when Bhaktivedanta Svāmī objected that the type was not large enough. He wanted twelve-point type, but the Radha Press had only ten-point. So Mr. Sharma agreed to take the work to another printer, Mr. Gautam Sharma of O.K. Press.

| | Radha Press ya había producido gran parte de los dos primeros capítulos cuando Bhaktivedanta Svāmī objetó que la letra no era lo suficientemente grande. Quería una tipografía de doce puntos, pero Radha Press solo tenía diez puntos. Entonces, el Sr. Sharma acordó llevar el trabajo a otra impresora, el Sr. Gautam Sharma de Prensa O.K.

|  | In printing Bhaktivedanta Svāmī’s Volume One of the First Canto of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, O.K. Press printed four book pages twice on a side of one sheet of paper twenty by twenty-six inches. But before running the full eleven hundred copies, they would print a proof, which Bhaktivedanta Svāmī would read. Then, following the corrected proofs, the printers would correct the hand-set type and run a second proof, which Bhaktivedanta would also read. Usually he would also find errors on the second proof; if so, they would print a third. If he found no errors on the third proof, they would then print the final pages. At this pace Bhaktivedanta Svāmī was able to order small quantities of paper as he could afford it – from six to ten reams at a time, ordered two weeks in advance.

| | Al imprimir el Volumen Uno de Bhaktivedanta Svāmī del Primer Canto del Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, la Imprenta O.K. imprimió cuatro páginas del libro dos veces en un lado de una hoja de papel de 50x60 centímetros. Antes de ejecutar las mil doscientas copias completas imprimirían una prueba que Bhaktivedanta Svāmī leería. Luego, siguiendo las pruebas corregidas, las impresoras corregirían los errores a mano y realizarían una segunda prueba, que Bhaktivedanta también leería. Por lo general también encontraría errores en la segunda prueba; si es así, imprimirían un tercero. Si no encontraba errores en la tercera prueba, imprimirían las páginas finales. A este ritmo, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī pudo ordenar pequeñas cantidades de papel como podía permitirse: de seis a diez resmas a la vez, ordenadas con dos semanas de anticipación.

|  | Even as the volume was being printed, he was still writing the last chapters. When the proofs were ready at O.K. Press, he would pick up the proofs, return to his room at Chippiwada, correct the proofs, and then return them. Sometimes fourteen-year-old Kantvedi, who lived at the Chippiwada temple with his parents, would carry the proofs back and forth for the Svāmī. But in the last months of 1962, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī usually made a daily walk to O.K. Press.

| | Incluso mientras se imprimía el volumen, seguía escribiendo los últimos capítulos. Cuando las pruebas estuvieron listas en la Imprenta O.K., recogería las pruebas, regresaría a su habitación en Chippiwada, corregiría las pruebas y luego las devolvería. A veces, Kantvedi, de catorce años, que vivía en el templo de Chippiwada con sus padres, llevaba consigo las pruebas de Svāmī. Pero en los últimos meses de 1962, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī solía hacer una caminata diaria a la Imprenta O.K.

|  | His walk through the tight, crowded lanes of Chippiwada soon led him to a road close to the Jama Mosque, and that road led into the noisy, heavily trafficked Chawri Bazaar. The neighborhood was a busy paper district, where laborers with ropes strapped across their shoulders pulled stout wooden carts, heavily loaded with stacks of paper, on small iron wheels. For two blocks, paper dealers were the only businesses – Hari Ram Gupta and Company, Roop Chand and Sons, Bengal Paper Mill Company Limited, Universal Traders, Janta Paper Mart – one after another even down the side alleys.

| | Su paseo por los estrechos y abarrotados carriles de Chippiwada pronto lo condujo a un camino cerca de la Mezquita Jama, ese camino condujo al ruidoso y denso tráfico de Chawri Bazaar. El vecindario era un concurrido distrito de papel, donde los trabajadores con cuerdas atadas a los hombros tiraban de carros de madera robustos, cargados con pilas de papel, sobre pequeñas ruedas de hierro. Durante dos bloques, los comerciantes de papel fueron los únicos negocios: Hari Ram Gupta y Compañía, Roop Chand e Hijos, Compañía Paaper Mill de Bengal Limitada, Comerciantes Unniversales, Mercado de Papel Janta, uno tras otro, incluso en los callejones laterales.

|  | The neighborhood storefronts were colorful and disorderly. Pedestrian traffic was so hectic that for a person to dally even for a moment would cause a disruption. Carts and rickshas carried paper and other goods back and forth through the streets. Sometimes a laborer would jog past with a hefty stack of pages on his head, the stack weighing down on either end. Traffic was swift, and an unmindful or slow-footed pedestrian risked being struck by a load protruding from the head of a bearer or from a passing cart. Occasionally a man would be squatting on the roadside, smashing chunks of coal into small pieces to sell. Tiny corner smoke shops drew small gatherings of customers for cigarettes or pān(2). The shopkeeper would rapidly spread the pān spices on a betel leaf, and the customer would walk off down the street chewing the pān and spitting out red-stained saliva.

| | Los escaparates del barrio eran coloridos y desordenados. El tráfico de peatones era tan agitado que, el que una persona se detuviera incluso por un momento causaría una interrupción. Carros y rickshas llevaban papel y otros bienes de un lado a otro por las calles. A veces, un trabajador pasaba corriendo con una gran pila de páginas en la cabeza, la pila pesaba en cada extremo. El tráfico era rápido y un peatón despreocupado o lento corría el riesgo de ser golpeado por una carga que sobresalía de la cabeza de un portador o de un carro que pasaba. Ocasionalmente, un hombre estaría en cuclillas al borde de la carretera, rompiendo trozos de carbón en pedazos pequeños para vender. Las pequeñas tabaquerías en los rincones generaban pequeñas reuniones de clientes para fumar cigarrillos o pān. El comerciante esparciría rápidamente las especias de pān(2) en una hoja de betel, el cliente caminaría calle abajo masticando el pān y escupiendo saliva manchada de rojo.

|  | Amidst this milieu, as the Chawri Bazaar commercial district blended into tenement life and children played in the hazardous streets, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī was a gentle-looking yet determined figure. As he walked past the tenements, the tile sellers, the grain sellers, the sweet shops, and the printers, overhead would be electric wires, pigeons, and the clotheslines from the tenement balconies. Finally he would come to O.K. Press, directly across from a small mosque. He would come, carrying the corrected proofs, to anxiously oversee the printing work.

| | En medio de este entorno, cuando el distrito comercial de Chawri Bazaar se mezcló con la vida de la vivienda y los niños jugaban en las peligrosas calles, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī era una figura de aspecto gentil pero determinada. Al pasar junto a las viviendas, los vendedores de azulejos, los vendedores de granos, las confiterías y las impresoras, en lo alto, tendrían cables eléctricos, palomas y los tendederos desde los balcones de las viviendas. Finalmente llegaba a la Imprenta O.K., directamente frente a una pequeña mezquita. Llegaba llevando las pruebas corregidas, para supervisar ansiosamente el trabajo de impresión.

|  | After four months, when the whole book had been printed and the sheets were stacked on the floor of the press, Mr. Hitsaran Sharma arranged for the work to be moved to a bindery. The binding was done by an ancient operation, mostly by hand, and it took another month. Bhaktivedanta Svāmī would come and observe the workers. A row of men sat in a small room, surrounded by stacks of printed paper. The first man would take one of the large printed sheets, rapidly fold it twice, and pass it to the next man, who performed the next operation. The pages would be folded, stitched, and collated, then put into a vise and hammered together before being trimmed on three sides with a handsaw and glued. Bit by bit, the book would be prepared for the final hard cover.

| | Después de cuatro meses, cuando se imprimió todo el libro y las hojas se apilaron en el piso de la imprenta, el Sr. Hitsaran Sharma hizo los arreglos para que el trabajo fuera trasladado a una encuadernación. La encuadernación se realizó mediante una operación antigua, principalmente a mano, tardó otro mes. Bhaktivedanta Svāmī venía y observaba a los trabajadores. Una fila de hombres se sentó en una pequeña habitación, rodeada de montones de papel impreso. El primer hombre tomaba una de las grandes hojas impresas, la doblaba rápidamente dos veces y se la pasaba al siguiente hombre, quien realizó la mismo operación. Las páginas se doblaban, se cosían y cotejaban, luego se colocaban en un tornillo de banco y se martillaban antes de recortarlas por tres lados con una sierra de mano y se pegaban. Poco a poco, el libro se preparaba para la final tapa dura.

|  | In addition to his visits to O.K. Press and the bindery, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī would also occasionally travel by bus across the Yamunā River to Mr. Hitsaran Sharma’s Radha Press. The Radha Press was printing one thousand dust jackets for the volume.

| | Además de sus visitas a la Imprenta O.K. y la encuadernación, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī, también viajaban ocasionalmente en autobús a través del río Yamunā a Radha Press, del Sr. Hitsaran Sharma. Radha Press estaba imprimiendo mil sobrecubiertas para el volumen.

|  | Hitsaran Sharma: Svāmīji was going hither and thither. He was getting whatever collections he could and depositing them. And he was always mixing with many persons, going hither and thither. With me he was very fond that I should do everything as soon as possible. He had a great haste. He used to say, “Time is going, time is going. Quick, do it!” He would be annoyed with me also, and he would have me do his work first. But I was in the service of Dalmia, and I would tell him, “Your work has to be secondary for me.” But he would say, “Now you have wasted my two days. What is this, Sharmaji? I am coming here, I told you in the morning to do this, and you have not done it even now.” But I would reply, “I have got no time during the day.” Then he would say, “Then you have wasted my complete day.” So he was very much pressing me. This was his temperament.

| | Hitsaran Sharma: Svāmīji iba de acá para allá. Estaba colectando todos las donativos que podía y los depositába. Siempre se mezclaba con muchas personas, yendo de un lado a otro. A mí le gustaba mucho que hiciera todo lo antes posible. Tuvo una gran prisa. Solía decir: “El tiempo se va, el tiempo se va. ¡Rápido, hazlo! Estaba molesto conmigo también, me haría hacer su trabajo primero. Pero estaba al servicio de Dalmia y le decía: “Tu trabajo tiene que ser secundario para mí". Pero él decía: “Ahora has perdido mis dos días. ¿Qué es esto, Sharmaji? Voy a venir aquí, te dije por la mañana que hicieras esto, y aún no lo has hecho. Pero respondía: “No tengo tiempo durante el día". Luego decía: “Entonces has desperdiciado mi día completo". Así que me estaba presionando mucho. Este era su temperamento.

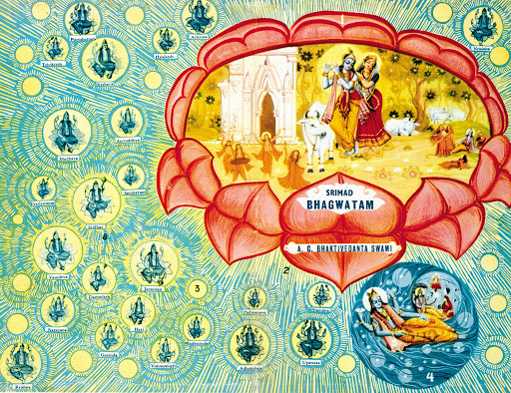

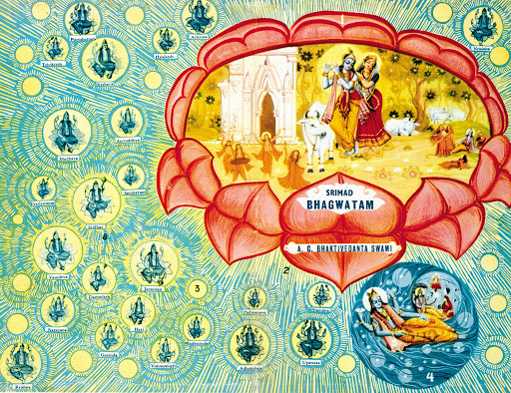

|  | The binding was reddish, the color of an earthen brick, and was inlaid with gold lettering. Bhaktivedanta Svāmī had designed the dust jacket himself, and he had commissioned a young Bengali artist named Salit to execute it. It was a wraparound picture of the entire spiritual and material manifestations. Dominating the front cover was a pink lotus, and within its whorl were Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa and Their pastimes in Vṛndāvana, along with Lord Caitanya chanting and dancing with His associates. From Kṛṣṇa’s lotus planet emanated yellow rays of light, and in that effulgence were many spiritual planets, appearing like so many suns. Sitting within each planet was a different four-armed form of Nārāyaṇa, each with His name lettered beneath the planet: Trivikrama, Keśava, Puruṣottama, and so on. Within an oval at the bottom of the front cover, Mahā-Viṣṇu was exhaling the material universes. On the inside cover was Bhaktivedanta Svāmī’s explanation of the cover illustration.

| | La encuadernación era rojiza, del color de un ladrillo de tierra y tenía incrustaciones en letras doradas. Bhaktivedanta Svāmī había diseñado la sobrecubierta él mismo y encargó a un joven artista bengalí llamado Salit que la ejecutara. Era una imagen envolvente de todas las manifestaciones espirituales y materiales. Dominando la portada había un loto rosa, dentro de su espiral estaban Rādhā y Kṛṣṇa y Sus pasatiempos en Vṛndāvana, junto con el Señor Caitanya cantando y bailando con Sus asociados. Del planeta de loto de Kṛṣṇa emanaban rayos de luz amarillos, en esa refulgencia había muchos planetas espirituales, apareciendo como tantos soles. Sentado dentro de cada planeta había una forma diferente de Nārāyaṇa con cuatro brazos, cada uno con Su nombre escrito debajo del planeta: Trivikrama, Keśava, Puruṣottama, y así sucesivamente. Dentro de un óvalo en la parte inferior de la portada, Mahā-Viṣṇu exhalaba los universos materiales. En la portada interior estaba la explicación de Bhaktivedanta Svāmī de la ilustración de la portada.

|  | When the printing and binding were completed, there were eleven hundred copies. Bhaktivedanta Svāmī would receive one hundred copies, and the printer would keep the balance. From the sale of the one hundred copies, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī would continue to pay off his debt to the printer and binder; then he would receive another supply of books. This would continue until he had finished paying his debt. His plan was to then publish a second volume from the profits of the first, and a third volume from the profits of the second.

| | Cuando se completó la impresión y la encuadernación, había mil cien copias. Bhaktivedanta Svāmī recibiría cien copias y la impresora mantendría el equilibrio. De la venta de las cien copias, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī continuaría pagando su deuda con la imprenta y el encuadernador; entonces recibiría otro suministro de libros. Esto continuaría hasta que terminara de pagar su deuda. Su plan era publicar un segundo volumen de las ganancias del primero y un tercer volumen con las ganancias del segundo.

|  | Kantvedi went to pick up the first one hundred copies. He hired a man who put the books in large baskets, placed them on his hand truck, and then hauled them through the streets to the Chippiwada temple, where Bhaktivedanta Svāmī stacked them in his room on a bench.

| | Kantvedi fue a recoger las primeras cien copias. Contrató a un hombre que puso los libros en grandes canastas, los colocó en su carretilla de mano y luego los arrastró por las calles hasta el templo Chippiwada, donde Bhaktivedanta Svāmī los apiló en un banco de su habitación.

|  | Bhaktivedanta Svāmī went out alone to sell his books and present them to important people. Dr. Radhakrishnan, who gave him a personal audience, agreed to read the book and write his opinion. Hanuman Prasad Poddar was the first to write a favorable review:

| | Bhaktivedanta Svāmī salió solo a vender sus libros y presentarlos a personas importantes. El Dr. Radhakrishnan, quien le dio una audiencia personal, aceptó leer el libro y escribir su opinión. Hanuman Prasad Poddar fue el primero en escribir una crítica favorable:

|  | “It is a source of great pleasure for me that a long cherished dream has materialised and is going to be materialised with this and the would-be publications. I thank the Lord that due to His grace this publication could see the light.”

| | «Para mí es una gran satisfacción que se haya materializado un sueño largo y preciado y que se va a materializar con esta y las futuras publicaciones. Agradezco al Señor que, debido a Su gracia, esta publicación pudo ver la luz».

|  | Bhaktivedanta Svāmī went to the major libraries, universities, and schools in Delhi, where the librarians found him “calm and quiet,” “noble,” “polite,” “scholarly,” “with a specific glow in him.” Traveling on foot, he visited school administration offices throughout Delhi and placed copies in more than forty schools in the Delhi area. The Ministry of Education (which had previously denied him assistance) placed an order for fifty copies for selected university and institutional libraries throughout India. The ministry paid him six hundred rupees plus packing and postage charges, and Bhaktivedanta Svāmī mailed the books to the designated libraries. The U.S. embassy purchased eighteen copies, to be distributed in America through the Library of Congress.

| | Bhaktivedanta Svāmī fue a las principales bibliotecas, universidades y escuelas de Delhi, donde los bibliotecarios lo encontraron. “tranquilo y silencioso",. “noble",. “educado",. “académico",. “con un brillo específico en él". Viajando a pie, visitó las oficinas de administración escolar en toda Delhi y colocó copias en más de cuarenta escuelas en el área de Delhi. El Ministerio de Educación (que anteriormente le había negado la asistencia) hizo un pedido de cincuenta copias para bibliotecas universitarias e institucionales seleccionadas en toda la India. El ministerio le pagó seiscientas rupias más gastos de embalaje y envío, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī envió los libros por correo a las bibliotecas designadas. La embajada de los Estados Unidos compró dieciocho copias, que se distribuirán en Estados Unidos a través de la Biblioteca del Congreso.

|  | The institutional sales were brisk, but then sales slowed. As the only agent, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī was now spending hours just to sell a few copies. He was eager to print the second volume, yet until enough money came from the first, he could not print. In the meantime he continued translating and writing purports. Writing so many volumes was a huge task that would take many years. And at his present rate, with sales so slow, he would not be able to complete the work in his lifetime.

| | Las ventas institucionales fueron rápidas, pero luego las ventas disminuyeron. Como único agente, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī ahora pasaba horas solo para vender algunas copias. Estaba ansioso por imprimir el segundo volumen, pero hasta que salió suficiente dinero del primero, no lo pudo imprimir. Mientras tanto, continuó traduciendo y escribiendo significados. Escribir tantos volúmenes fue una tarea enorme que tomaría muchos años. A su ritmo actual y con las ventas tan lentas, no podría completar el trabajo en su vida.

|  | Although there were many who took part in the production of the book and still others who became customers, only Bhaktivedanta Svāmī deeply experienced the successes and failures of the venture. It was his project, and he was responsible. No one was eager to see him writing prolifically, and no one demanded that it be printed. Even when the sales slowed to a trickle, the managers of O.K. Press were not distressed; they would give him the balance of his books only when he paid for them. And since it was also he who had the burden of hiring O.K. Press to print a second volume, the pressure was on him to go out and sell as many copies of the first volume as possible. For Hanuman Prasad Poddar, the volume had been something to admire in passing; for Hitsaran Sharma, it had been something he had tended to after his day’s work for Mr. Dalmia; for the boy who lived at Chippiwada, the book had meant a few errands; for the paper dealers it had meant a small order; for Dr. Radhakrishnan it had been but the slightest, soon-forgotten matter in a life crammed with national politics and Hindu philosophizing. But Bhaktivedanta Svāmī, by his full engagement in producing the Bhāgavatam, felt bliss and assurance that Kṛṣṇa was pleased. He did not, however, intend for the Bhāgavatam to be his private affair. It was the sorely needed medicine for the ills of Kali-yuga, and it was not possible for only one man to administer it. Yet he was alone, and he felt exclusive pleasure and satisfaction in serving his guru and Lord Kṛṣṇa. Thus his transcendental frustration and pleasure mingled, his will strengthened, and he continued alone.

| | Aunque hubo muchos que participaron en la producción del libro y otros que se convirtieron en clientes, solo Bhaktivedanta Svāmī experimentó profundamente los éxitos y fracasos de la empresa. Era su proyecto y él era el responsable. Nadie estaba ansioso por verlo escribir prolíficamente y nadie le exigió que se imprimiera. Incluso cuando las ventas se ralentizaron, los administradores de la Imprenta de O.K. no estaba angustiadoa; le darían el saldo de sus libros solo cuando los pagara. Y como también era él quien tenía la carga de contratar a la Imprenta O.K. para imprimir un segundo volumen, se presionó para salir y vender tantas copias del primer volumen como fuera posible. Para Hanuman Prasad Poddar, el volumen había sido algo admirable de inicio; para Hitsaran Sharma, había sido algo a lo que había tendido después de su día de trabajo para el Sr. Dalmia; para el niño que vivía en Chippiwada, el libro había significado algunos recados; para los vendedores de papel significaba un pedido pequeño; para el Dr. Radhakrishnan no había sido más que el más mínimo asunto olvidado en una vida repleta de políticas nacionales y filosofías hindúes. Pero Bhaktivedanta Svāmī, por su compromiso total en la producción del Bhāgavatam, sintió dicha y seguridad de que Kṛṣṇa estaba complacido. Sin embargo, no tenía la intención de que el Bhāgavatam fuera su asunto privado. Era la medicina tan necesaria para los males de Kali-yuga y no era posible que solo un hombre la administrara. Sin embargo, estaba solo y sentía un placer y satisfacción exclusivos al servir a su guru y al Señor Kṛṣṇa. Así, su frustración y placer trascendentales se mezclaron, su voluntad se fortaleció y continuó solo.

|  | His spiritual master, the previous spiritual masters, and the Vedic scriptures all assured him that he was right. If a person got a copy of the Bhāgavatam and read even one page, he might decide to take part in Lord Caitanya’s movement. If a person seriously read the book, he would be convinced about spiritual life. The more this book could be distributed, the more the people could understand Kṛṣṇa consciousness. And if they understood Kṛṣṇa consciousness, they would become liberated from all problems. Bookselling was real preaching. Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī had wanted it, even at the neglect of constructing temples or making followers. Who could preach as well as Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam? Certainly whoever spent sixteen rupees for a book would also take the time at least to look at it.

| | Su maestro espiritual, los maestros espirituales anteriores y las escrituras védicas le aseguraron que tenía razón. Si una persona obtuvo una copia del Bhāgavatam y leyó incluso una página, podría decidir participar en el movimiento del Señor Caitanya. Si una persona leyera seriamente el libro, estaría convencido de la vida espiritual. Cuanto más se pudiera distribuir este libro, más podría la gente entender la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa. Y si entienden la Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa, se liberarán de todos los problemas. La venta de libros era una verdadera prédica. Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī lo había deseado, incluso al descuidar la construcción de templos o hacer seguidores. ¿Quién podría predicar tan bien como el Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam? Ciertamente, quien haya gastado dieciséis rupias por un libro también se tomaría el tiempo al menos para mirarlo.

|  | In the months that followed, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī received more favorable reviews. The prestigious Adyar Library Bulletin gave a full review, noting “the editor’s vast and deep study of the subject” and concluding, “Further volumes of this publication are eagerly awaited.”

| | En los meses que siguieron, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī recibió críticas más favorables. El prestigioso Boletín de la Biblioteca Adyar hizo una revisión completa, destacando. “el estudio extenso y profundo del tema por parte del editor.” y concluyendo: “Se esperan ansiosamente más volúmenes de esta publicación".

|  | His scholarly Godbrothers also wrote their appreciations. Svāmī Bon Mahārāja, rector of the Institute of Oriental Philosophy in Vṛndāvana, wrote:

| | Sus hermanos espirituales también escribieron sus apreciaciones. Svāmī Bon Mahārāja, rector del Instituto de Filosofía Oriental en Vṛndāvana, escribió:

|  | “I have nothing but admiration for your bold and practical venture. If you should be able to complete the whole work, you will render a very great service to the cause of Prabhupada Sri Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati Gosvāmī Maharaj, Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu and the country also. Do it and rest assured there will be no scarcity of resources.”

| | «No tengo nada más que admiración por su audaz y práctica aventura. Si puede completar todo el trabajo, prestará un gran servicio a la causa de Prabhupada Sri Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati Gosvāmī Maharaj, Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu y también al país. Hágalo y tenga la seguridad de que no habrá escasez de recursos».

|  | Bhaktisāraṅga Mahārāja wrote a full review in his Sajjana-toṣaṇī.

| | Bhaktisāraṅga Mahārāja escribió una reseña completa en su Sajjana-toṣaṇī.

|  | “We expect that this particular English version of Srimad Bhagwatam will be widely read and thereby spiritual poverty of people in general may be removed forever. At a time when we need it very greatly, Srimad Bhaktivedanta Svāmī has given us the right thing. We recommend this publication for everyone’s serious study.”

| | «Esperamos que esta versión particular en inglés del Srimad Bhagwatam se lea ampliamente y por lo tanto, que la pobreza espiritual de las personas en general se elimine para siempre. Es un momento en que lo necesitamos mucho, Srimad Bhaktivedanta Svāmī nos ha dado lo correcto. Recomendamos esta publicación para el estudio serio de todos».

|  | Śrī Biswanath Das, governor of Uttar Pradesh, commended the volume to all thoughtful people. And Economic Review praised the author for attempting a tremendous task.

| | Śrī Biswanath Das, gobernador de Uttar Pradesh, recomendó el volumen a todas las personas reflexivas. Y Economic Review elogió al autor por intentar una tarea tan tremenda.

|  | “At a time when not only the people of India but those of the West need the chastening quality of love and truth in the corrupting atmosphere of hate and hypocrisy, a work like this will have uplifting and corrective influence.”

| | «En un momento en que no solo la gente de India sino también la de Occidente necesitan el castigo de calidad del amor y la verdad en la atmósfera corruptora del odio y la hipocresía, un trabajo como este tendrá una influencia edificante y correctiva».

|  | Dr. Zakir Hussain, vice president of India, wrote:

| | El Dr. Zakir Hussain, vicepresidente de India, escribió:

|  | “I have read your book Srimad Bhagwatam with great interest and much profit. I thank you again for the kind thought which must have prompted you to present it to me.”

| | «He leído su libro Srimad Bhagavatam con gran interés y mucho beneficio. Le agradezco nuevamente por el amable pensamiento que debe haberle impulsado a que me lo presente».

|  | The favorable reviews, although Bhaktivedanta Svāmī could not pay the printer with them, indicated a serious response; the book was valuable. And subsequent volumes would earn the series even more respect. By Kṛṣṇa’s grace, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī had already completed many of the translations and purports for Volume Two. Even in the last weeks of printing the first volume, he had been writing day and night for the second volume. It was glorification of the Supreme Lord, Kṛṣṇa, and therefore it would require many, many volumes. He felt impelled to praise Kṛṣṇa and describe Him in more and more volumes. Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī had said that the presses of the world could not print fast enough the glories of Kṛṣṇa and the spiritual world that were being received at every moment by pure devotees.

| | Las críticas eran favorables, aunque Bhaktivedanta Svāmī no pudo pagarle a la impresora, indicaron una respuesta seria; El libro fue valioso. Y los volúmenes posteriores le ganarían a la serie aún más respeto. Por la gracia de Kṛṣṇa, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī ya había completado muchas de las traducciones y significados para el Volumen Dos. Incluso en las últimas semanas de imprimir el primer volumen, había estado escribiendo día y noche para el segundo volumen. Era la glorificación del Señor Supremo, Kṛṣṇa, por lo tanto requeriría muchos, muchos volúmenes. Se sintió impulsado a alabar a Kṛṣṇa y describirlo en más y más volúmenes. Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī había dicho que las prensas del mundo no podían imprimir lo suficientemente rápido las glorias de Kṛṣṇa y el mundo espiritual que recibían en todo momento los devotos puros.

|  | Bhaktivedanta Svāmī decided to return to Vṛndāvana for several months of intensive writing on Volume Two. This was his real business at Rādhā-Dāmodara temple. Vṛndāvana was the best place for writing transcendental literature; that had already been demonstrated by the Vaiṣṇava ācāryas of the past. Living in simple ease, taking little rest and food, he continually translated the verses and composed his Bhaktivedanta purports for Volume Two. After a few months, after amassing enough manuscript pages, he would return to Delhi and once again enter the world of publishing.

| | Bhaktivedanta Svāmī decidió regresar a Vṛndāvana por varios meses de escritura intensiva en el Volumen Dos. Este era su verdadero deber en el templo Rādhā-Dāmodara. Vṛndāvana era el mejor lugar para escribir literatura trascendental; eso ya había sido demostrado por los ācāryas vaiṣṇavas del pasado. Viviendo con facilidad, descansando y comiendo poco, tradujo continuamente los versos y compuso sus significados de Bhaktivedanta para el Volumen Dos. Después de unos meses, después de acumular suficientes páginas de manuscritos, volvería a Delhi y una vez más entraría en el mundo editorial.

|  | In Volume One he had covered the first six-and-a-half chapters of the First Canto. The second volume began on page 365 with the eighth verse of the Seventh Chapter. Bhaktivedanta Svāmī wrote in his purport that the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam was meant for paramahaṁsas, persons engaged purely in self-realization. “Yet,” he wrote, “it works into the depth of the heart of those who may be worldly men. Worldly men are all engaged in the matter of sense gratification. But even such men also will find in this Vedic literature a remedial measure for their material diseases.”

| | En el Volumen Uno había cubierto los primeros seis capítulos y medio del Primer Canto. El segundo volumen comenzó en la página 365 con el octavo verso del Séptimo Capítulo. Bhaktivedanta Svāmī escribió en su significado que el Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam estaba destinado a paramahaṁsas, personas dedicadas exclusivamente a la autorrealización. “Sin embargo”, escribió, “funciona en el fondo del corazón de aquellos que pueden ser hombres mundanos. Todos los hombres del mundo están involucrados en la cuestión de la complacencia de los sentidos. Pero incluso esos hombres también encontrarán en esta literatura védica una medida correctiva para sus enfermedades materiales".

|  | Bhaktivedanta Svāmī returned to Delhi to raise funds for printing Volume Two. When he visited a prospective donor, he would show the man Volume One and the growing collection of reviews, explaining that he was asking a donation not to support himself but to print this important literature. Although for the first volume he had received no donations equal to the four thousand rupees he had received from Mr. Poddar, an executive in the L&H Sugar factory gave a donation of five thousand rupees for Volume Two.

| | Bhaktivedanta Svāmī regresó a Delhi para recaudar fondos para imprimir el Volumen Dos. Cuando visitaba a un posible donante, le mostraría al hombre el Volumen Uno y la creciente colección de reseñas, explicando que estaba pidiendo una donación no para mantenerse, sino para imprimir esta importante literatura. Aunque para el primer volumen no había recibido donaciones iguales a las cuatro mil rupias que había recibido del Sr. Poddar, un ejecutivo de la fábrica de azúcar L&H hizo una donación de cinco mil rupias para el Volumen Dos.

|  | Bhaktivedanta Svāmī had been dissatisfied with Hitsaran Sharma as a production supervisor. Although supposedly an expert in the trade, Hitsaran had caused delays, and sometimes he had advised Gautam Sharma without consulting Bhaktivedanta Svāmī. The work on Volume One had slowed and even stopped when a job from a cash customer had come up, and Bhaktivedanta Svāmī had complained that it was Hitsaran’s fault for not giving money to O.K. Press on time. For Volume Two, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī decided to deal directly with O.K. Press and supervise the printing himself. He spoke to Gautam Sharma and offered a partial payment. Although the majority of the copies of Volume One were still standing on their printing floor, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī wanted O.K. Press to begin Volume Two. Gautam Sharma accepted the job.

| | Bhaktivedanta Svāmī no estaba satisfecho con Hitsaran Sharma como supervisor de producción. Aunque supuestamente era un experto en el comercio, Hitsaran había causado demoras y a veces, había aconsejado a Gautam Sharma sin consultar a Bhaktivedanta Svāmī. El trabajo en el Volumen Uno se había ralentizado e incluso se detuvo cuando apareció un trabajo de un cliente en efectivo y Bhaktivedanta Svāmī se quejó de que fue culpa de Hitsaran por no dar dinero a la Imprenta O.K. a tiempo. Para el Volumen Dos, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī decidió tratar directamente con la Imprenta O.K. y supervisar la impresión él mismo. Habló con Gautam Sharma y le ofreció un pago parcial. Aunque la mayoría de las copias del Volumen Uno todavía estaban en pie en su piso de impresión, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī quería a laImprenta O.K. para comenzar el Volumen Dos. Gautam Sharma aceptó el trabajo.

|  | It was early in 1964 when Volume Two went to press, following the same steps as Volume One. But this time Bhaktivedanta Svāmī was more actively present, pushing. To avoid delays, he purchased the paper himself. At Siddho Mal and Sons Paper Merchants, in the heart of the paper district, he would choose and order his paper and then arrange to transport it to O.K. Press. If the order was a large one he would have it carried by cart; smaller orders he would send by ricksha or on the head of a bearer.

| | Fue a principios de 1964 cuando el Volumen Dos fue a la imprenta, siguiendo los mismos pasos que el Volumen Uno. Pero esta vez Bhaktivedanta Svāmī estuvo presente más activamente, empujando. Para evitar demoras, compró el papel él mismo. En Comercializadora de Papel Siddho Mal e Hijos, en el corazón del distrito de papel, él elegiría y ordenaría su papel y luego organizaría su transporte a la Imprenta O.K. Si el pedido fuera grande, lo llevaría en carro; órdenes más pequeñas se enviarían por ricksha o en la cabeza de un portador.

|  | In his Preface to the second volume, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī expressed the apparent oddity of working in Delhi while living in Vṛndāvana.

| | En su Prefacio al segundo volumen, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī expresó la aparente rareza de trabajar en Delhi mientras vivía en Vṛndāvana.

|  | “The path of fruitive activities i.e. to say the path of earn money and enjoy life, as it is going on generally, appears to have become also our profession although we have renounced the order of worldly life! They see that we are moving in the cities, in the Government offices, banks and other business places for promoting the publication of Srimad Bhagwatam. They also see that we are moving in the press, paper market and amongst the book binders also away from our residence at Vrindaban, and thus they conclude sometimes mistakenly that we are also doing the same business in the dress of a mendicant!”

| | «¡El camino de las actividades fruitivas, es decir, el camino de ganar dinero y disfrutar de la vida, como está sucediendo en general, parece haberse convertido también en nuestra profesión, aunque hemos renunciado al orden de la vida mundana! Ven que nos estamos mudando a las ciudades, oficinas gubernamentales, bancos y otros lugares comerciales para promover la publicación del Srimad Bhagwatam. También ven que nos estamos mudando a la imprenta, el mercado de papel y entre las carpetas de libros también fuera de nuestra residencia en Vrindaban, por lo tanto, ¡a veces concluyen erróneamente que también estamos haciendo el mismo negocio con el ropaje de un mendigo!».

|  | “But actually there is a gulf of difference between the two kinds of activities. This is not a business for maintaining an establishment of material enjoyment. On the contrary it is an humble attempt to broadcast the glories of the Lord at a time when the people need it very badly.”

| | «Pero en realidad hay una gran diferencia entre los dos tipos de actividades. Este no es un negocio para mantener un establecimiento de disfrute material. Por el contrario, es un intento humilde de transmitir las glorias del Señor en un momento en que la gente lo necesita con urgencia».

|  | He went on to describe how in former days, even fifty years ago, well-to-do members of society had commissioned paṇḍitas to print or handwrite the Bhāgavatam and then distribute copies amongst the devotees and the general people. But times had changed.

| | Continuó describiendo cómo en días anteriores, incluso hace cincuenta años, los miembros acomodados de la sociedad habían comisionado a los paṇḍitas para imprimir o escribir a mano el Bhāgavatam y luego distribuir copias entre los devotos y la gente en general. Pero los tiempos habían cambiado.

|  | “At the present moment the time is so changed that we had to request one of the biggest industrialists of India, to purchase 100 (one hundred) copies and distribute them but the poor fellow expressed his inability. We wished that somebody may come forward to pay for the actual cost of publication of this Srimad Bhagwatam and let them be distributed free to all the leading gentlemen of the world. But nobody is so far prepared to do this social uplifting work.”

| | «En este momento, el tiempo ha cambiado tanto que tuvimos que solicitar a uno de los mayores industriales de la India que comprara 100 (cien) copias y las distribuyera, pero el pobre hombre expresó su incapacidad. Deseamos que alguien pudiera pagar el costo real de la publicación de este Srimad Bhagwatam y dejar que se distribuya gratuitamente a todos los principales caballeros del mundo. Pero hasta ahora nadie está preparado para hacer este elevado trabajo social».

|  | After thanking the Ministry of Education and the director of education for distributing copies to institutions and libraries, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī again stated his predicament before his reading public.

| | Después de agradecer al Ministerio de Educación y al director de educación por distribuir copias a instituciones y bibliotecas, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī volvió a declarar su situación antes de su lectura pública.

|  | “The problem is that we must get some money for completing the work which is admittedly a mighty project. The sales proceeds are being employed in the promotional work and not in sense gratification. Herein lies the difference from the fruitive activities. And for all this we have to approach everyone concerned just like a businessman. There is no harm to become a businessman if it is done on account of the Lord as much as there was no harm to become a violent warrior like Arjuna or Hanumanji if such belligerent activities are executed to satisfy the desires of the Supreme Lord.”

| | «El problema es que debemos obtener algo de dinero para completar el trabajo, lo que sin duda es un proyecto poderoso. Los ingresos de las ventas se están empleando en el trabajo de promoción y no en la gratificación de los sentidos. Aquí radica la diferencia de las actividades fruitivas. Y por todo esto, tenemos que acercarnos a todos los interesados como un hombre de negocios. No es perjudicial convertirse en un hombre de negocios si se hace a causa del Señor tanto como no hubo daño en convertirse en un guerrero violento como Arjuna o Hanumanji si tales actividades beligerantes se ejecutan para satisfacer los deseos del Señor Supremo».

|  | “So even though we are not in the Himalayas, even though we talk of business, even though we deal in rupees and paisa, still, simply because we are 100 per cent servants of the Lord and are engaged in the service of broadcasting the message of His glories, certainly we shall transcend and get through the invincible impasse of Maya and reach the effulgent kingdom of God to render Him face to face eternal service, in full bliss and knowledge. We are confident of this factual position and we may also assure to our numerous readers that they will also achieve the same result simply by hearing the glories of the Lord.”

| | «Entonces, aunque no estemos en el Himalaya, aunque hablemos de negocios, aunque negociemos en rupias y paisa, aún así, simplemente porque somos servidores al 100 por ciento del Señor y estamos comprometidos en el servicio de transmitir el mensaje de Sus glorias, ciertamente trascenderemos y atravesaremos el invencible callejón sin salida de Maya y llegaremos al refulgente reino de Dios para rendirle cara a cara el servicio eterno, en plena felicidad y conocimiento. Confiamos en esta posición objetiva y también podemos asegurar a nuestros numerosos lectores que también lograrán el mismo resultado simplemente escuchando las glorias del Señor».

|  | On receipt of the first copies of the second volume – another four-hundred-page, clothbound, brick-colored Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, with the same dust jacket as Volume One – Bhaktivedanta Svāmī made the rounds of the institutions, scholars, politicians, and booksellers. One Delhi bookseller, Dr. Manoharlal Jain, had particular success in selling the volumes.

| | Al recibir las primeras copias del segundo volumen, otro Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam de cuatrocientas páginas, encuadernado en tela y color ladrillo, con la misma sobrecubierta que el Volumen Uno, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī recorrió las instituciones, académicos, políticos y libreros. Un librero de Delhi, el Dr. Manoharlal Jain, tuvo un éxito particular en la venta de los volúmenes.

|  | Manoharlal Jain: He would come to me for selling his books. He would come often, and he used to chat with me for one or two hours. He had no other business except selling his books as much as possible. We would discuss the difficulties he was having and also many other things – yoga, Vedānta, and religious aspects of life. His problem was distributing his work, because it was a big publication. He had planned to publish it in many volumes. Naturally, I told him it was not possible for any individual bookseller or publisher here to publish it and invest money in it. So that was a little bit of a disappointment for him because he could not bring out more volumes.

| | Manoharlal Jain: Él vendría a mí por vender sus libros. Él venía a menudo, y solía conversar conmigo durante una o dos horas. No tenía más asuntos que vender sus libros tanto como fuera posible. Hablabamos de las dificultades que estaba teniendo y también muchas otras cosas: yoga, vedanta y aspectos religiosos de la vida. Su problema era distribuir su trabajo, porque era una gran publicación. Había planeado publicarlo en muchos volúmenes. Naturalmente, le dije que no era posible que un librero o editor individual lo publicara e invirtiera dinero en él. Así que fue un poco decepcionante para él porque no pudo sacar más volúmenes.

|  | But my sales were good because this was the best translation – Sanskrit text with English translations. No other such edition was available. I sold about one hundred and fifty to two hundred copies in about two or three years. The price was very little, only sixteen rupees. He had published his reviews, and he had a good sell, a good market. The price was reasonable, and he was not interested in making money out of it. He was printing in English, for the foreigners. He had a good command of Sanskrit as well as English. When we met, we would speak in English, and his English was very impressive.

| | Pero mis ventas fueron buenas porque esta fue la mejor traducción: texto sánscrito con traducciones al inglés. Ninguna otra edición de este tipo estaba disponible. Vendí entre ciento cincuenta y doscientas copias en aproximadamente dos o tres años. El precio era muy bajo, solo dieciséis rupias. Había publicado sus comentarios y tenía una buena venta, un buen mercado. El precio era razonable y no estaba interesado en ganar dinero con él. Estaba imprimiendo en inglés, para los extranjeros. Tenía un buen dominio del sánscrito y del inglés. Cuando nos conocimos, hablamos en inglés, su inglés era muy impresionante.

|  | He wanted me to publish, but I didn’t have any presses and no finances. I told him frankly I would not be able to publish it, because it was not one or two volumes but many. But he managed anyhow. I referred him to Atmaram and Sons. He also used to go there.

| | Quería que publicara, pero yo no tenía ninguna prensa ni capital. Le dije francamente que no podría publicarlo, porque no era uno o dos volúmenes, sino muchos. Pero se las arregló de todos modos. Lo remití a Atmaram e Hijos. También solía ir allí.

|  | He was a great master, a philosopher, a great scholar. I used to enjoy the talks. He used to sit with me for one or two hours, as much as he could afford. Sometimes he would come in the morning, eleven or twelve, and then sometimes in the afternoon. He used to come in for money: “How many copies are sold?” So I would pay him. Practically, he was not doing very well with finances at that time. He only wanted that his books should be sold to every library and everywhere where the people are interested in it.

| | Fue un gran maestro, un filósofo, un gran erudito. Solía disfrutar las conversaciones. Solía sentarse conmigo durante una o dos horas, tanto como podía permitirse. Algunas veces venía por la mañana, once o doce, otras veces por la tarde. Solía venir por dinero: “¿Cuántas copias se vendieron?.” Entonces le pagaba. Prácticamente, no estaba muy bien con las finanzas en ese momento. Solo quería que sus libros se vendieran a todas las bibliotecas y en todas partes donde la gente estuviera interesada en ellos.

|  | We used to publish a catalog every month, and I would advertise his book. Orders would be coming from all over the world. So, at least for me, the sales were picking up. If I sold one hundred copies of the first volume, then I figured the second volume would be sold in the same number, naturally. But definitely those who would take the first volume would also take Volume Two, because it was institutional and the institutions will always try to complete their set. He used to discuss with me how the volumes can be brought out and how many it would take to complete the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam. He was very much interested in bringing out the whole series.

| | Solíamos publicar un catálogo cada mes, yo anunciaba su libro. Venían pedidos de todo el mundo. Entonces, al menos para mí, las ventas estaban aumentando. Si vendiera cien copias del primer volumen, entonces pensé que el segundo volumen se vendería en el mismo número, naturalmente. Pero definitivamente aquellos que tomarían el primer volumen también tomarían el Volumen Dos, porque era institucional y las instituciones siempre tratarán de completar su conjunto. Solía planear conmigo cómo se pueden sacar los volúmenes y cuántos se necesitarían para completar el Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam. Estaba muy interesado en sacar toda la serie.

|  | In January of 1964, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī was granted an interview with Indian vice president Zakir Hussain, who, although a Muslim, had written an appreciation of Bhaktivedanta Svāmī’s Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam. As Dr. Hussain cordially received the author at the presidential palace, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī spoke of the importance of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam in the cause of love of Godhead. But Dr. Hussain wanted to know how love of Godhead could help humanity. The question, put by ruler to sādhu, was filled with philosophical implications, but the vice president’s busy schedule of meetings did not permit Bhaktivedanta Svāmī to answer fully. For the vice president the interview was a gesture of appreciation, recognizing the Svāmī for his work on behalf of India’s Hindu cultural heritage. And Bhaktivedanta Svāmī humbly accepted the ritual.

| | En enero de 1964, a Bhaktivedanta Svāmī se le concedió una entrevista con el vicepresidente indio Zakir Hussain, quien, aunque era musulmán, había escrito una apreciación del Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam de Bhaktivedanta Svāmī. Cuando el Dr. Hussain recibió cordialmente al autor en el palacio presidencial, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī habló de la importancia del Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam en la causa del amor a Dios. Pero el Dr. Hussain quería saber cómo el amor a Dios podría ayudar a la humanidad. La pregunta, formulada por el gobernante al sādhu estaba llena de implicaciones filosóficas, pero la apretada agenda de reuniones del vicepresidente no permitió que Bhaktivedanta Svāmī respondiera completamente. Para el vicepresidente, la entrevista fue un gesto de agradecimiento, reconociendo al Svāmī por su trabajo en nombre del patrimonio cultural de la India y Bhaktivedanta Svāmī aceptó humildemente el ritual.

|  | Later, however, he wrote Dr. Hussain a long letter, answering the question he had not had time to answer during their brief meeting. “… Mussalmans [Muslims] also admit,” he wrote, “that ‘There is nothing greater than Allah.’ The Christians also admit that ‘God is Great.’ … The human society must learn to obey the laws of God.” He reminded Dr. Hussain of India’s great cultural asset the Vedic literature; the Indian government could perform the best welfare work for humanity by disseminating Vedic knowledge in a systematic way. Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam was “produced in India”; it was the substantial contribution India could offer to the world.

| | Sin embargo, más tarde le escribió al Dr. Hussain una gran carta, respondiendo la pregunta que no había tenido tiempo de responder durante su breve reunión. “... Mussalmans [los musulmanes] también admiten", escribió,. “que.” No hay nada más grande que Alá". Los cristianos también admiten que.” Dios es grande"... La sociedad humana debe aprender a obedecer las leyes de Dios". Le recordó al Dr. Hussain el gran activo cultural de la India, la literatura védica; El gobierno indio podría realizar el mejor trabajo de bienestar para la humanidad diseminando el conocimiento védico de manera sistemática. El Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam fue. “producido en la India"; es la contribución substancial que India puede ofrecer al mundo.

|  | In March of 1964, Kṛṣṇa Pandit, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī’s sponsor at the Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa temple in Chippiwada, arranged for him to reside for a few months at the Śrī Rādhāvallabhajī temple in the nearby Rosanpura Naisarak neighborhood. There he could continue his writing and publishing, but he would also be giving a series of lectures. Kṛṣṇa Pandit provided Bhaktivedanta Svāmī about fifteen hundred rupees for his maintenance. On Bhaktivedanta Svāmī’s arrival at Śrī Rādhāvallabhajī temple, the manager distributed notices inviting people to “take full advantage of the presence of a Vaishnava Sadhu.” As “resident ācārya,” Bhaktivedanta Svāmī held morning and evening discourses at the temple, without reducing his activities of writing and printing.

| | En marzo de 1964, Kṛṣṇa Pandit, patrocinador de Bhaktivedanta Svāmī en el templo Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa en Chippiwada, hizo los arreglos para que residiera durante unos meses en el templo Śrī Rādhāvallabhajī en el cercano vecindario de Rosanpura Naisarak. Allí podría continuar escribiendo y publicando, pero también estaría dando una serie de conferencias. Kṛṣṇa Pandit proporcionó a Bhaktivedanta Svāmī unas mil quinientas rupias para su mantenimiento. A la llegada de Bhaktivedanta Svāmī al templo de Śrī Rādhāvallabhajī, el administrador distribuyó avisos invitando a las personas a. “aprovechar al máximo la presencia de un sadhu vaishnava". Como. “ācārya residente", Bhaktivedanta Svāmī realizó discursos matutinos y vespertinos en el templo, sin reducir sus actividades de escritura e impresión.

|  | In June, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī got the opportunity to meet Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri. The meeting had been arranged by Doladram Khannah, a wealthy jeweler who was a trustee of the Chippiwada temple and had often met with Bhaktivedanta Svāmī there. An old friend of Prime Minister Shastri’s since his youth, when they had attended the same yoga club, Mr. Khannah arranged the meeting as a favor to Bhaktivedanta Svāmī. Let the prime minister meet a genuine sādhu, Mr. Khannah thought.

| | En junio, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī tuvo la oportunidad de reunirse con el primer ministro Lal Bahadur Shastri. La reunión había sido organizada por Doladram Khannah, un adinerado joyero que era administrador del templo Chippiwada y que a menudo se había reunido allí con Bhaktivedanta Svāmī. Un viejo amigo del primer ministro Shastri desde su juventud, cuando habían asistido al mismo club de yoga, el Sr. Khannah organizó la reunión como un favor para Bhaktivedanta Svāmī. Que el primer ministro se encuentre con un sādhu genuino, pensó Khannah.

|  | It was a formal occasion in the gardens of the Parliament Building, and the prime minister was meeting a number of guests. Prime Minister Shastri, dressed in white kurtā and dhotī and a Nehru hat and surrounded by aides, received the elderly sādhu. Bhaktivedanta Svāmī, looking scholarly in his spectacles, stepped forward and introduced himself – and his book, Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam. As he handed the prime minister a copy of Volume One, a photographer snapped a photo of the author and the prime minister smiling over the book.

| | Fue una ocasión formal en los jardines del edificio del Parlamento, el primer ministro se reunió con varios invitados. El primer ministro Shastri, vestido con una kurtā blanca y dhotī y un sombrero Nehru y rodeado de ayudantes, recibió al anciano sādhu. Bhaktivedanta Svāmī, mirando al erudito con sus gafas, dio un paso adelante, se presentó y a su libro, El Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam. Mientras le entregaba al primer ministro una copia del Volumen Uno, un fotógrafo tomó una foto del autor y el primer ministro sonriendo sobre el libro.

|  | The next day, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī wrote to Prime Minister Shastri. He soon received a reply, personally signed by the prime minister:

| | Al día siguiente, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī le escribió al primer ministro Shastri. Pronto recibió una respuesta, firmada personalmente por el primer ministro:

|  | “Dear Svāmīji, Many thanks for your Letter. I am indeed grateful to you for Presenting a copy of “Srimad Bhagwatam” to me. I do realise that you are doing valuable work. It would be good idea if the libraries in the Government Institutions purchase copies of this book.”

| | «Estimado Svāmīji: Muchas gracias por su carta. De hecho, estoy agradecido por presentarme una copia del. “Srimad Bhagwatam". Me doy cuenta de que estás haciendo un trabajo valioso. Sería una buena idea que las bibliotecas de las instituciones gubernamentales compren copias de este libro».

|  | Bhaktivedanta Svāmī wrote back to the prime minister, requesting him to buy books for Indian institutions. Mr. R. K. Sharma of the Ministry of Education subsequently wrote back, confirming that they would take fifty copies of Volume Two, just as they had taken Volume One.

| | Bhaktivedanta Svāmī le respondió al primer ministro, solicitándole que compre libros para las instituciones indias. Posteriormente, el Sr. R. K. Sharma, del Ministerio de Educación, respondió, confirmando que tomarían cincuenta copias del Volumen Dos, tal como lo hicieron con el Volumen Uno.

|  | To concentrate on completing Volume Three, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī returned to the Rādhā-Dāmodara temple. These were the last chapters of the First Canto, dealing with the advent of the present Age of Kali. There were many verses foretelling society’s degradation and narrating how the great King Parīkṣit had staved off Kali’s influence by his strong Kṛṣṇa conscious rule. In his purports, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī wrote that government could not check corruption unless it rooted out the four basic principles of irreligion – meat-eating, illicit sex, intoxication, and gambling. “You cannot check all these evils of society simply by statutory acts of police vigilance but you have to cure the disease of mind by the proper medicine namely advocating the principles of Brahminical culture or the principles of austerity, cleanliness, mercy, and truthfulness. … We must always remember that false pride … undue attachment for woman or association with them and intoxicating habit of all … description will cripple the human civilisation from the path of factual peace, however the people may go on clamouring for such peace of the world.”

| | Para concentrarse en completar el Volumen Tres, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī regresó al templo Rādhā-Dāmodara. Estos fueron los últimos capítulos del Primer Canto, que tratan del advenimiento de la actual Era de Kali. Había muchos versos que predecían la degradación de la sociedad y narraban cómo el gran Rey Parīkṣit había evitado la influencia de Kali por su fuerte gobierno en Conciencia de Kṛṣṇa. En sus pretensiones, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī escribió que el gobierno no puede controlar la corrupción a menos que elimine los cuatro principios básicos de la irreligión: comer carne, sexo ilícito, intoxicación y juegos de azar. “No puedes controlar todos estos males de la sociedad simplemente mediante actos legales de vigilancia policial, sino que debes curar la enfermedad mental con la medicina adecuada, es decir, defender los principios de la cultura brahmínica o los principios de austeridad, limpieza, misericordia y veracidad.” ...Siempre debemos recordar que el falso orgullo... el apego indebido por la mujer o la asociación con ellos y el hábito embriagador de todos... la descripción desviará a la civilización humana del camino de la paz fáctica, sin embargo, la gente puede seguir clamando por esa paz del mundo."

|  | To raise funds for Volume Three, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī decided to try Bombay. He traveled there in July and stayed at the Premkutir Dharmshala, a free āśrama.

| | Para recaudar fondos para el Volumen Tres Bhaktivedanta Svāmī decidió probar Bombay. Viajó allí en julio y se quedó en el Premkutir Dharmshala, un āśrama gratuito.

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda: At Premkutir they received me very nicely. I was going to sell my books. Some of them were criticizing, “What kind of sannyāsī? He is making business bookselling.” Not the authorities said this, but some of them. I was writing my book then also.

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda: En Premkutir me recibieron muy amablemente. Iba a vender mis libros. Algunos de ellos criticaban: “¿Qué tipo de sannyāsī? Está haciendo negocios de venta de libros. Las autoridades no dijeron esto, pero si algunos. Mientras estaba escribiendo mi libro entonces.

|  | Then I became a guest for fifteen days with a member of the Dalmia family. One of the brothers told me that he wanted to construct a little cottage at his house: “You can live here. I will give you a nice cottage.” I thought, “No, it is not good to be fully dependent and patronized by a viṣayī [materialist].” But I stayed for fifteen days, and he gave me exclusive use of a typewriter for writing my books.

| | Luego fui invitado durante quince días con un miembro de la familia Dalmia. Uno de los hermanos me dijo que quería construir una casita en su casa: “Puedes vivir aquí. Te daré una bonita cabaña. Pensé: “No, no es bueno ser totalmente dependiente y patrocinado por un viṣayī [materialista]". Pero me quedé quince días y él me dio el uso exclusivo de una máquina de escribir para escribir mis libros.

|  | Bhaktivedanta Svāmī made his rounds of the institutions and booksellers in Bombay. He now had an advertisement showing himself with Prime Minister Shastri, and he also had the prime minister’s letter and the Ministry of Education’s purchase order for fifty volumes. Still, he was getting only small orders.

| | Bhaktivedanta Svāmī recorrió las instituciones y libreros de Bombay. Ahora tenía un anuncio que se mostraba con el primer ministro Shastri, también tenía la carta del primer ministro y la orden de compra del Ministerio de Educación por cincuenta volúmenes. Aun así, solo recibía pequeños pedidos.

|  | Then he decided to visit Sumati Morarji, head of the Scindia Steamship Company. He had heard from his Godbrothers in Bombay that she was known for helping sādhus and had donated to the Bombay Gauḍīya Maṭh. He had never met her, but he well remembered the 1958 promise by one of her officers to arrange half-fare passage for him to America. Now he wanted her help for printing Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam.

| | Luego decidió visitar a Sumati Morarji, jefe de la Compañía de Buque Scindia. Había escuchado de sus hermanos espirituales en Bombay que ella era conocida por ayudar a sādhus y que había donado a la Gauḍīya Maṭh de Bombay. Nunca la había conocido, pero recordaba bien la promesa de uno de sus oficiales de 1958 de organizarle un pasaje de media tarifa para él a Estados Unidos. Ahora requería de su ayuda para imprimir el Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam.

|  | But his first attempts to arrange a meeting were unsuccessful. Frustrated at being put off by Mrs. Morarji’s officers, he sat down on the front steps of her office building, determined to catch her attention as she left for the day. The lone sādhu certainly caused some attention as he sat quietly chanting for five hours on the steps of the Scindia Steamship Company building. Finally, late that afternoon, Mrs. Morarji emerged in a flurry of business talk with her secretary, Mr. Choksi. Upon seeing Bhaktivedanta Svāmī, she stopped. “Who is this gentleman sitting here?” she asked Mr. Choksi.

| | Pero sus primeros intentos de concertar una reunión no tuvieron éxito. Frustrado de los oficiales de la Sra. Morarji, se sentó en los escalones del frente de su edificio de oficinas decidido a llamar su atención cuando ella saliera por el día. El solitario sādhu sin duda causó cierta atención mientras permanecía sentado cantando en silencio durante cinco horas en los escalones del edificio de la Compañía de Buques de vapor Scindia. Finalmente, a última hora de la tarde, la Sra. Morarji surgió en una serie de conversaciones de negocios con su secretario, el Sr. Choksi. Al ver a Bhaktivedanta Svāmī, se detuvo. “¿Quién es este caballero sentado aquí?.” le preguntó al señor Choksi.

|  | “He’s been here for five hours,” the secretary said.

| | "Ha estado aquí por cinco horas", dijo el secretario.

|  | “All right, I’ll come,” she said and walked up to where Bhaktivedanta Svāmī was sitting. He smiled and stood, offering namaskāras with his folded palms. “Svāmīji, what can I do for you?” she said.

| | "Está bien, iré", dijo y caminó hacia donde estaba sentado Bhaktivedanta Svāmī. Él sonrió y se puso de pie, ofreciendo namaskāras con sus palmas juntas. “Svāmīji, ¿qué puedo hacer por ti?.” dijo ella.

|  | Bhaktivedanta Svāmī told her briefly of his intentions to print the third volume of his Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam. “I want you to help me,” he said.

| | Bhaktivedanta Svāmī le contó brevemente sus intenciones de imprimir el tercer volumen de su Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam. “Quiero que me ayudes", dijo.

|  | “All right,” Mrs. Morarji replied. “We can meet tomorrow, because it is getting late. Tomorrow you can come, and we will discuss.”

| | "Está bien", respondió la Sra. Morarji. “Podemos encontrarnos mañana, porque se está haciendo tarde. Mañana puedes venir, y lo hablaremos.

|  | The next day, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī met with Mrs. Morarji in her office, where she looked at the typed manuscript and the published volumes. “All right,” she said, “if you want to print it, I will give you the aid. Whatever you want. You can get it printed.”

| | Al día siguiente, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī se reunió con la Sra. Morarji en su oficina, donde mostró el manuscrito mecanografiado y los volúmenes publicados. “Muy bien”, dijo ella, “si quieres imprimirlo, te daré la ayuda. Lo que quieras. Puedes imprimirlo.

|  | With Mrs. Morarji’s guarantee, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī was free to return to Vṛndāvana to finish writing the manuscript. As with the previous volumes, he set a demanding schedule for writing and publishing. The third volume would complete the First Canto. Then, with a supply of impressive literature, he would be ready to go to the West. Even with volumes One and Two he was getting a better reception in India. Already he had seen the vice president and prime minister. He had successfully approached a big business magnate of Bombay, and within a few minutes of presenting the book, he had received a large donation. The books were powerful preaching.

| | Con la garantía de la Sra. Morarji, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī fue libre de regresar a Vṛndāvana para terminar de escribir el manuscrito. Al igual que con los volúmenes anteriores, estableció un calendario exigente para escribir y publicar. El tercer volumen completaría el Primer Canto. Luego, con un suministro de literatura impresionante, estaría listo para ir a Occidente. Incluso con los volúmenes uno y dos estaba recibiendo una mejor recepción en la India. Ya había visto al vicepresidente y al primer ministro. Se había acercado con éxito a un magnate de las grandes empresas de Bombay, y a los pocos minutos de presentar el libro recibió una gran donación. Los libros son una prédica poderosas.

|  | Janmāṣṭamī was drawing near, and Bhaktivedanta Svāmī was planning a celebration at the Rādhā-Dāmodara temple. He wanted to invite Biswanath Das, the governor of Uttar Pradesh, to preside over the ceremony honoring Lord Kṛṣṇa’s appearance. Śrī Biswanath had received a copy of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam Volume One and had written a favorable review. Although a politician, he was known for his affection and respect for sādhus. He regularly invited recognized sādhus to his home, and once a year he would visit all the important temples of Maṭhurā and Vṛndāvana. Bhaktivedanta Svāmī asked Vṛndāvana’s municipal president, Mangalal Sharma, to invite the governor to the Janmāṣṭamī celebration at Rādhā-Dāmodara temple. The governor readily accepted the invitation.

| | Janmāṣṭamī se estaba acercando y Bhaktivedanta Svāmī estaba planeando una celebración en el templo Rādhā-Dāmodara. Quería invitar a Biswanath Das, el gobernador de Uttar Pradesh a presidir la ceremonia en honor a la aparición del Señor Kṛṣṇa. Sri Biswanath había recibido una copia del Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam Volumen Uno y escribió una crítica favorable. Aunque político, era conocido por su afecto y respeto por los sādhus. Invitaba regularmente a sādhus reconocidos a su hogar, una vez al año visitaba todos los templos importantes de Maṭhurā y Vṛndāvana. Bhaktivedanta Svāmī le pidió al presidente municipal de Vṛndāvana, Mangalal Sharma, que invitara al gobernador a la celebración de Janmāṣṭamī en el templo de Rādhā-Dāmodara. El gobernador aceptó fácilmente la invitación.

|  | Bhaktivedanta Svāmī printed a flyer announcing:“On the Occasion of JANMASTAMI ceremony at

The Samadhi ground of Srila Rupa and Jeeva Gosvāmī

SRI SRI RADHA DAMODAR TEMPLE

Sebakunj, Vrindaban.

Goudiya Kirtan Performances

In the Presence of

His Excellency Sri Biswanath Das

GOVERNOR OF UTTAR PRADESH

&

The chief Guest SRI G. D. SOMANI of Bombay

Trustee of Sri Ranganathji Temple, Vrindaban.

Dated at Vrindaban Sunday the 31st August, 1964 at 7-30 to 8-30 p.m.”

| | Bhaktivedanta Svāmī imprimió un volante anunciando:«Con motivo de la ceremonia de JANMASTAMI en

El terreno del Samadhi de Srila Rupa y Jiva Gosvāmī

EL TEMPLO DE SRI SRI RADHA DAMODAR

Sebakunj, Vrindaban.

Actuaciones del Goudiya Kirtan

En la presencia de

Su Excelencia Sri Biswanath Das

GOBERNADOR DE UTTAR PRADESH

Y

El jefe invitado SRI G. D. SOMANI de Bombay

Fideicomisario del Templo Sri Ranganathji, Vrindaban.

Fechado en Vrindaban el domingo 31 de agosto de 1964 a las 7-30 para 8-30 p.m.».

|  | The flyer contained an advertisement for the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam series, to be completed in sixty volumes. Bhajanas to be sung on the occasion – “Śrī Kṛṣṇa Caitanya Prabhu,” “Nitāi-pada-kamala,” the “Prayers to the Six Gosvāmīs,” and other favorite songs of the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavas – were printed in Bengali as a songbook.

| | El volante contenía un anuncio de la serie del Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, que se completará en sesenta volúmenes. En la ocasión se cantaban bhajanas: “Śrī Kṛṣṇa Caitanya Prabhu",. “Nitāi-pada-kamala", las. “Oraciones a los seis Gosvāmīs.” y otras canciones favoritas de los vaiṣṇavas gauḍīya, se imprimieron en bengalí como un cancionero.

|  | The program was successful. A large crowd attended and sang songs to Lord Kṛṣṇa and took prasādam. Bhaktivedanta Svāmī lectured on a verse from Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam describing the Age of Kali as an ocean of faults that had but one saving quality: the chanting of Hare Kṛṣṇa. After leading Hare Kṛṣṇa kīrtana, Bhaktivedanta Svāmī presented a copy of his second volume of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam to the governor and spoke of his plans to preach all over the world.