|

Śrīla Prabhupāda Līlambṛta - — Śrīla Prabhupāda Līlambṛta

Volume I — A lifetime in preparation — Volumen I — Toda una vida en preparación

<< 1 Childhood >> — << 1 Infancia >>

| “We would be sleeping, and father would be doing ārati. Ding ding ding – we would hear the bell and wake up and see him bowing down before Kṛṣṇa.”

— Śrīla Prabhupāda

| | «Estaríamos durmiendo y mi papá hacía un ārati. Ding ding ding: oíamos la campana y nos despertábamos, lo veíamos inclinándose ante Kṛṣṇa.».

— Śrīla Prabhupāda

|  | IT WAS JANMĀṢṬAMĪ, the annual celebration of the advent of Lord Kṛṣṇa some five thousand years before. Residents of Calcutta, mostly Bengalis and other Indians, but also many Muslims and even some British, were observing the festive day, moving here and there through the city’s streets to visit the temples of Lord Kṛṣṇa. Devout Vaiṣṇavas, fasting until midnight, chanted Hare Kṛṣṇa and heard about the birth and activities of Lord Kṛṣṇa from Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam. They continued fasting, chanting, and worshiping throughout the night.

| | ERA JANMĀṢṬAMĪ, la celebración anual del advenimiento del Señor Kṛṣṇa ocurrida unos cinco mil años antes. Los residentes de Calcuta, en su mayoría bengalíes y otros indios, también muchos musulmanes e incluso algunos británicos, observaban el día festivo, moviéndose aquí y allá por las calles de la ciudad para visitar los templos del Señor Kṛṣṇa. Devotos Vaiṣṇavas, ayunando hasta la medianoche, cantaron Hare Kṛṣṇa y escucharon acerca del nacimiento y las actividades del Señor Kṛṣṇa del Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam. Continuaron ayunando, cantando y haciendo adoración durante la noche.

|  | The next day (September 1, 1896), in a little house in the Tollygunge suburb of Calcutta, a male child was born. Since he was born on Nandotsava, the day Kṛṣṇa’s father, Nanda Mahārāja, had observed a festival in honor of Kṛṣṇa’s birth, the boy’s uncle called him Nandulal. But his father, Gour Mohan De, and his mother, Rajani, named him Abhay Charan, “one who is fearless, having taken shelter at Lord Kṛṣṇa’s lotus feet.” In accordance with Bengali tradition, the mother had gone to the home of her parents for the delivery, and so it was that on the bank of the Ādi Gaṅgā, a few miles from his father’s home, in a small two-room, mud-walled house with a tiled roof, underneath a jackfruit tree, Abhay Charan was born. A few days later, Abhay returned with his parents to their home at 151 Harrison Road.

| | Al día siguiente (1 de septiembre de 1896), en una pequeña casa en el suburbio Tollygunge de Calcuta, nació un niño varón. Como nació en Nandotsava, el día que el padre de Kṛṣṇa, Nanda Mahārāja, realizó un festival en honor del nacimiento de Kṛṣṇa, el tío del niño lo llamó Nandulal. Pero su padre, Gour Mohan De y su madre, Rajani, lo llamaron Abhay Charan, “uno que no tiene miedo, habiéndose refugiado en los pies de loto del Señor Kṛṣṇa”. De acuerdo con la tradición bengalí, la madre fue a la casa de sus padres para el parto, así fue que en la orilla del Ādi Gaṅgā, a unos pocos kilómetros de la casa de su padre, en una pequeña casa de barro de dos habitaciones, casa amurallada con techo de tejas, debajo de un árbol de jaca, nació Abhay Charan. Unos días después, Abhay fue con sus padres a su casa en el 151 de la Calle Harrison.

|  | An astrologer did a horoscope for the child, and the family was made jubilant by the auspicious reading. The astrologer made a specific prediction: When this child reached the age of seventy, he would cross the ocean, become a great exponent of religion, and open 108 temples.

| | Un astrólogo hizo un horóscopo para el niño, la familia se sintió jubilosa por la auspiciosa lectura. El astrólogo hizo una predicción específica: cuando este niño cumpla los setenta años, cruzará el océano, se convertirá en un gran exponente de la religión y abrirá 108 templos.

|  | Abhay Charan De was born into an India dominated by Victorian imperialism. Calcutta was the capital of India, the seat of the viceroy, the Earl of Elgin and Kincardine, and the “second city” of the British Empire. Europeans and Indians lived separately, although in business and education they intermingled. The British lived mostly in central Calcutta, amidst their own theaters, racetracks, cricket fields, and fine European buildings. The Indians lived more in north Calcutta. Here the men dressed in dhotīs and the women in sārīs and, while remaining loyal to the British Crown, followed their traditional religion and culture.

| | Abhay Charan De nació en una India dominada por el imperialismo victoriano. Calcuta era la capital de la India, la sede del virrey, el Conde de Elgin y Kincardine, la “segunda ciudad” del Imperio Británico. Europeos e indios vivían separados, aunque en los negocios y la educación se entremezclaban. Los británicos vivían principalmente en el centro de Calcuta, en medio de sus propios teatros, hipódromos, campos de cricket y hermosos edificios europeos. Los indios vivían más en el norte de Calcuta. Allí los hombres se vestían con dhotīs, las mujeres con sārīs y mientras permanecían leales a la corona británica, seguían su religión y cultura tradicionales.

|  | Abhay’s home at 151 Harrison Road was in the Indian section of north Calcutta. Abhay’s father, Gour Mohan De, was a cloth merchant of moderate income and belonged to the aristocratic suvarṇa-vaṇik merchant community. He was related, however, to the wealthy Mullik family, which for hundreds of years had traded in gold and salt with the British. Originally the Mulliks had been members of the De family, a gotra (lineage) that traces back to the ancient sage Gautama; but during the Mogul period of pre-British India a Muslim ruler had conferred the title Mullik (“lord”) on a wealthy, influential branch of the Des. Then, several generations later, a daughter of the Des had married into the Mullik family, and the two families had remained close ever since.

| | La casa de Abhay en el 151 de la Calle Harrison estaba en la sección india del norte de Calcuta. El padre de Abhay, Gour Mohan De, era un comerciante de telas de ingresos moderados y pertenecía a la comunidad aristocrática de comerciantes suvarṇa-vaṇik. Sin embargo estaba emparentado con la rica familia Mullik, que durante cientos de años comerció con oro y sal con los británicos. Originalmente, los Mullik eran miembros de la familia De, un gotra (linaje) que se remonta al antiguo sabio Gautama; pero durante el período mogol de la India prebritánica, un gobernante musulmán les confirió el título de Mullik ("señor") a una rama rica e influyente de los De. Varias generaciones más tarde, una hija de un De se casó con un miembro de la familia Mullik y las dos familias han permanecido unidas desde entonces.

|  | An entire block of properties on either side of Harrison Road belonged to Lokanath Mullik, and Gour Mohan and his family lived in a few rooms of a three-story building within the Mullik properties. Across the street from the Des’ residence was a Rādhā-Govinda temple where for the past 150 years the Mulliks had maintained worship of the Deity of Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa. Various shops on the Mullik properties provided income for the Deity and for the priests conducting the worship. Every morning before breakfast, the Mullik family members would visit the temple to see the Deity of Rādhā-Govinda. They would offer cooked rice, kacaurīs, and vegetables on a large platter and would then distribute the prasādam to the Deities’ morning visitors from the neighborhood.

| | Un bloque completo de propiedades a ambos lados de la Calle Harrison pertenecía a Lokanath Mullik, Gour Mohan y su familia vivían en algunas habitaciones de un edificio de tres pisos dentro de las propiedades de Mullik. Al otro lado de la calle de la residencia de los De había un templo de Rādhā-Govinda donde durante los últimos 150 años los Mulliks han adorado a la Deidad de Rādhā y Kṛṣṇa. Varias tiendas en las propiedades de los Mullik proporcionaron ingresos para la Deidad y para los sacerdotes que dirigían el culto. Todas las mañanas antes del desayuno, los miembros de la familia Mullik visitaban el templo para ver la Deidad de Rādhā-Govinda. Ofrecían arroz cocido, kacaurīs y verduras en un plato grande, luego distribuían el prasādam a los visitantes matutinos de las Deidades del vecindario.

|  | Among the daily visitors was Abhay Charan, accompanying his mother, father, or servant.

| | Entre los visitantes diarios estaba Abhay Charan, acompañando a su madre y padre o un sirviente.

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda: I used to ride on the same perambulator with Siddhesvar Mullik. He used to call me Moti (“pearl”), and his nickname was Subidhi. And the servant pushed us together. If one day this friend did not see me, he would become mad. He would not go in the perambulator without me. We would not separate even for a moment.

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda: Solía viajar en el mismo cochecito de niño con Siddhesvar Mullik. Solía llamarme Moti (“perla”), su apodo era Subidhi. El sirviente nos empujaba juntos. Si un día este amigo no me veía, se volvía loco. No iría en el cochecito sin mí. No nos separaríamos ni por un momento.

|  | As the servant pushed the baby carriage into the wide expanse of Harrison Road, timing his crossing between the bicycles and horse-drawn hackneys, the two children in the pram gazed up at the fair sky and tall trees across the road. Sounds and sights of the hackneys, with their large wheels spinning over the road, caught the fascinated attention of the two children. The servant steered the carriage towards the arched gateway within the red sandstone wall bordering the Rādhā-Govinda Mandira, and as Abhay and his friend rode underneath the ornate metal arch and into the courtyard, they saw high above them two stone lions, the heralds and protectors of the temple compound, their right paws extended.

| | Mientras el sirviente empujaba el cochecito de bebé por la amplia extensión de la Calle Harrison, cronometrando su cruce entre las bicicletas y los carruajes tirados por caballos, los dos niños en el cochecito miraban hacia el cielo claro y los altos árboles al otro lado de la calle. Los sonidos y las imágenes de los coches de alquiler, con sus grandes ruedas girando sobre la carretera, captaron la atención fascinada de los dos niños. El sirviente condujo el carruaje hacia la entrada arqueada dentro del muro de piedra arenisca roja que bordeaba el Mandira de Rādhā-Govinda, cuando Abhay y su amigo cabalgaron por debajo del arco de metal adornado y entraron al patio, vieron muy por encima de ellos dos leones de piedra, los heraldos y protectores del recinto del templo con sus patas derechas extendidas.

|  | In the courtyard was a circular drive, and on the oval lawn were lampposts with gaslights, and a statue of a young woman in robes. Sharply chirping sparrows flitted in the shrubs and trees or hopped across the grass, pausing to peck the ground, while choruses of pigeons cooed, sometimes abruptly flapping their wings overhead, sailing off to another perch or descending to the courtyard. Voices chattered as Bengalis moved to and fro, dressed in simple cotton sārīs and white dhotīs. Someone paused by the carriage to amuse the golden-skinned boys, with their shining dark eyes, but mostly people were passing by quickly, going into the temple.

| | En el patio había un camino circular y en el césped ovalado había farolas con luces de gas y una estatua de una mujer joven con túnica. Los gorriones que cantaban agudamente revoloteaban entre los arbustos y los árboles o saltaban sobre la hierba, deteniéndose para picotear el suelo, mientras coros de palomas arrullaban, a veces batiendo bruscamente sus alas sobre su cabeza, volando hacia otra percha o descendiendo al patio. Las voces charlaban mientras los bengalíes se movían de un lado a otro, vestidos con sencillos saris de algodón y dhotis blancos. Alguien se detuvo junto al carruaje para entretener a los muchachos de piel dorada, con sus brillantes ojos oscuros, pero la mayoría de la gente pasaba rápidamente, entrando al templo.

|  | The heavy double doors leading into the inner courtyard were open, and the servant eased the carriage wheels down a foot-deep (30 cm) step and proceeded through the foyer, then down another step and into the bright sunlight of the main courtyard. There they faced a stone statue of Garuḍa, perched on a four-foot (1.20 m) column. This carrier of Viṣṇu, Garuḍa, half man and half bird, kneeled on one knee, his hands folded prayerfully, his eagle’s beak strong, and his wings poised behind him. The carriage moved ahead past two servants sweeping and washing the stone courtyard. It was just a few paces across the courtyard to the temple.

| | Las pesadas puertas dobles que conducían al patio interior estaban abiertas, el sirviente bajó las ruedas del carruaje un peldaño de treinta centímetros de profundidad y atravesó el vestíbulo, luego bajó otro escalón y salió a la brillante luz del sol del patio principal. Allí se enfrentaron a una estatua de piedra de Garuḍa, encaramada en una columna de un metro y veinte centímetros. Este portador de Viṣṇu, Garuḍa, mitad hombre y mitad pájaro, estaba arrodillado sobre una rodilla, con las manos cruzadas en actitud de oración, su fuerte pico de águila y sus alas suspendidas detrás de él. El carruaje pasó delante de dos sirvientes que barrían y lavaban el patio de piedra. Sólo unos pocos pasos a través del patio hasta el templo.

|  | The temple area itself, open like a pavilion, was a raised platform with a stone roof supported by stout pillars fifteen feet (4.5 m) tall. At the left end of the temple pavilion stood a crowd of worshipers, viewing the Deities on the altar. The servant pushed the carriage closer, lifted the two boys out, and then, holding their hands, escorted them reverentially before the Deities.

| | El área del templo en sí, abierta como un pabellón, era una plataforma elevada con un techo de piedra sostenido por robustos pilares de cuatro metros y medio de altura. En el extremo izquierdo del pabellón del templo se encontraba una multitud de devotos, contemplando las Deidades en el altar. El sirviente empujó el carruaje más cerca, sacó a los dos niños, entonces tomándolos de la mano, los escoltó con reverencia ante las Deidades.

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda: I can remember standing at the doorway of Rādhā-Govinda temple saying prayers to Rādhā-Govinda mūrti. I would watch for hours together. The Deity was so beautiful, with His slanted eyes.

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda: Recuerdo estar de pie en la entrada del templo de Rādhā-Govinda rezando oraciones al mūrti de Rādhā-Govinda. Mirarbamos juntos durante horas. La Deidad era tan hermosa, con Sus ojos rasgados.

|  | Rādhā and Govinda, freshly bathed and dressed, now stood on Their silver throne amidst vases of fragrant flowers. Govinda was about eighteen (45 cm) inches high, and Rādhārāṇī, standing to His left, was slightly smaller. Both were golden. Rādhā and Govinda both stood in the same gracefully curved dancing pose, right leg bent at the knee and right foot placed in front of the left. Rādhārāṇī, dressed in a lustrous silk sārī, held up Her reddish right palm in benediction, and Kṛṣṇa, in His silk jacket and dhotī, played on a golden flute.

| | Rādhā y Govinda, recién bañados y vestidos, ahora estaban de pie en Su trono de plata en medio de jarrones de fragantes flores. Govinda medía unos cuarenta y cinco centímetros de alto, y Rādhārāṇī, de pie a Su izquierda, era un poco más pequeña. Ambos eran dorados. Rādhā y Govinda de pié en la misma pose de baile graciosamente curvada, la pierna derecha doblada a la altura de la rodilla y el pie derecho colocado delante del izquierdo. Rādhārāṇī, vestida con un lustroso sārī de seda, con Su palma derecha rojiza en señal de bendición y Kṛṣṇa, con Su chaqueta de seda y Su dhotī, tocando una flauta dorada.

|  | At Govinda’s lotus feet were green tulasī leaves with pulp of sandalwood. Hanging around Their Lordships’ necks and reaching down almost to Their lotus feet were several garlands of fragrant night-blooming jasmine, delicate, trumpetlike blossoms resting lightly on Rādhā and Govinda’s divine forms. Their necklaces of gold, pearls, and diamonds shimmered. Rādhārāṇī’s bracelets were of gold, and both She and Kṛṣṇa wore gold-embroidered silk cādaras about Their shoulders. The flowers in Their hands and hair were small and delicate, and the silver crowns on Their heads were bedecked with jewels. Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa were slightly smiling.

| | A los pies de loto de Govinda había hojas verdes de tulasī con pulpa de sándalo. Colgando del cuello de Sus Señorías y llegando casi hasta Sus pies de loto había varias guirnaldas de fragantes jazmines que florecían de noche, delicadas flores parecidas a trompetas que descansaban suavemente sobre las formas divinas de Rādhā y Govinda. Sus collares de oro, perlas y diamantes brillaban. Los brazaletes de Rādhārāṇī eran de oro y tanto Ella como Kṛṣṇa llevaban cādaras de seda bordadas en oro sobre Sus hombros. Las flores en Sus manos y cabello eran pequeñas y delicadas y las coronas de plata sobre Sus cabezas estaban adornadas con joyas. Rādhā y Kṛṣṇa sonreían levemente.

|  | Beautifully dressed, dancing on Their silver throne beneath a silver canopy and surrounded by flowers, to Abhay They appeared most attractive. Life outside, on Harrison Road and beyond, was forgotten. In the courtyard the birds went on chirping, and visitors came and went, but Abhay stood silently, absorbed in seeing the beautiful forms of Kṛṣṇa and Rādhārāṇī, the Supreme Lord and His eternal consort.

| | Bellamente vestidos, bailando en Su trono plateado bajo un dosel plateado y rodeados de flores, a Abhay le parecieron sumamente atractivos. La vida en el exterior, en la Calle Harrison y más allá, quedó en el olvido. En el patio, los pájaros seguían cantando y los visitantes iban y venían, pero Abhay permaneció en silencio, absorto en ver las hermosas formas de Kṛṣṇa y Rādhārāṇī, el Señor Supremo y Su eterna consorte.

|  | Then the kīrtana began, devotees chanting and playing on drums and karatālas. Abhay and his friend kept watching as the pūjārīs offered incense, its curling smoke hanging in the air, then a flaming lamp, a conchshell, a handkerchief, flowers, a whisk, and a peacock fan. Finally the pūjārī blew the conchshell loudly, and the ārati ceremony was over.

| | Entonces comenzó el kīrtana, los devotos cantaban y tocaban tambores y karatālas. Abhay y su amigo siguieron observando cómo los pūjārīs ofrecían incienso, su humo ondulante flotando en el aire, luego una lámpara encendida, una caracola, un pañuelo, flores, una chamara y un abanico de plumas de pavo real. Finalmente, el pūjārī hizo sonar la caracola con fuerza y la ceremonia ārati terminó.

|  | When Abhay was one-and-a-half years old, he fell ill with typhoid. The family physician, Dr. Bose, prescribed chicken broth.

| | Cuando Abhay tenía un año y medio, enfermó de fiebre tifoidea. El médico de la familia, el Dr. Bose, le recetó caldo de pollo.

|  | No, Gour Mohan protested, I cannot allow it.

Yes, otherwise he will die.

But we are not meat-eaters, Gour Mohan pleaded. We cannot prepare chicken in our kitchen.

Don’t mind, Dr. Bose said. I shall prepare it at my house and bring it in a jar, and you simply …

Gour Mohan assented. If it is necessary for my son to live. So the doctor came with his chicken broth and offered it to Abhay, who immediately began to vomit.

All right, the doctor admitted. Never mind, this is no good. Gour Mohan then threw the chicken broth away, and Abhay gradually recovered from the typhoid without having to eat meat.

| | No, protestó Gour Mohan, no puedo permitirlo.

Sí, de lo contrario morirá.

Pero no somos carnívoros, suplicó Gour Mohan. No podemos preparar pollo en nuestra cocina.

No importa, dijo el Dr. Bose. Yo lo prepararé en mi casa, lo traeré en un frasco y tú simplemente...

Gour Mohan asintió. Si es necesario para que mi hijo viva. Entonces el doctor vino con el caldo de pollo y se lo ofreció a Abhay, quien inmediatamente comenzó a vomitar.

Muy bien, admitió el doctor. No importa, esto no es bueno. Gour Mohan tiró el caldo de pollo y Abhay se recuperó gradualmente de la fiebre tifoidea sin tener que comer carne.

|  | On the roof of Abhay’s maternal grandmother’s house was a little garden with flowers, greenery, and trees. Along with the other grandchildren, two-year-old Abhay took pleasure in watering the plants with a sprinkling can. But his particular tendency was to sit alone amongst the plants. He would find a nice bush and make a sitting place.

| | En el techo de la casa de la abuela materna de Abhay había un pequeño jardín con flores, vegetación y árboles. Junto con los otros nietos, Abhay, de dos años, se complacía en regar las plantas con una regadera. Pero su particular tendencia era sentarse solo entre las plantas. Encontraba un buen arbusto y hacía un lugar para sentarse.

|  | One day when Abhay was three, he narrowly escaped a fatal burning. He was playing with matches in front of his house when he caught his cloth on fire. Suddenly a man appeared and put the fire out. Abhay was saved, although he retained a small scar on his leg.

| | Un día, cuando Abhay tenía tres años, escapó por poco de una quemadura fatal. Estaba jugando con fósforos frente a su casa cuando se incendió su ropa. De repente apareció un hombre y apagó el fuego. Abhay se salvó, aunque conservó una pequeña cicatriz en la pierna.

|  | In 1900, when Abhay was four, a vehement plague hit Calcutta. Dozens of people died every day, and thousands evacuated the city. When there seemed no way to check the plague, an old bābājī organized Hare Kṛṣṇa saṅkīrtana all over Calcutta. Regardless of religion, Hindu, Muslim, Christian, and Parsi all joined, and a large party of chanters traveled from street to street, door to door, chanting the names Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa, Hare Hare / Hare Rāma, Hare Rāma, Rāma Rāma, Hare Hare. The group arrived at Gour Mohan’s house at 151 Harrison Road, and Gour Mohan eagerly received them. Although Abhay was a little child, his head reaching only up to the knees of the chanters, he also joined in the dancing. Shortly after this, the plague subsided.

| | En 1900, cuando Abhay tenía cuatro años, una violenta plaga golpeó a Calcuta. Decenas de personas morían todos los días y miles evacuaban la ciudad. Cuando parecía que no había manera de controlar la plaga, un anciano bābājī organizó un saṅkīrtana Hare Kṛṣṇa por todo Calcuta. Independientemente de la religión, se unieron hindúes, musulmanes, cristianos y parsis, un gran grupo de cantores viajó de calle en calle, de puerta en puerta, cantando los nombres Hare Kṛṣṇa, Hare Kṛṣṇa, Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa, Hare Hare / Hare Rāma, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. El grupo llegó a la casa de Gour Mohan en el 151 de la Calle Harrison y Gour Mohan los recibió con entusiasmo. Aunque Abhay era un niño pequeño, su cabeza llegaba solo a las rodillas de los cantores, también se unió al baile. Poco después de esto, la plaga terminó.

|  | Gour Mohan was a pure Vaiṣṇava, and he raised his son to be Kṛṣṇa conscious. Since his own parents had also been Vaiṣṇavas, Gour Mohan had never touched meat, fish, eggs, tea, or coffee. His complexion was fair and his disposition reserved. At night he would lock up his cloth shop, set a bowl of rice in the middle of the floor to satisfy the rats so that they would not chew the cloth in their hunger, and return home. There he would read from Caitanya-caritāmṛta and Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, the main scriptures of Bengali Vaiṣṇavas, chant on his japa beads, and worship the Deity of Lord Kṛṣṇa. He was gentle and affectionate and would never punish Abhay. Even when obliged to correct him, Gour Mohan would first apologize: You are my son, so now I must correct you. It is my duty. Even Caitanya Mahāprabhu’s father would chastise Him, so don’t mind.

| | Gour Mohan fue un vaiṣṇava puro y crió a su hijo para que fuera consciente de Kṛṣṇa. Como sus propios padres también fueron vaiṣṇavas, Gour Mohan nunca probó la carne, el pescado, los huevos, el té o el café. Su tez era blanca y su disposición reservada. Por la noche cerraba su tienda de telas, ponía un tazón de arroz en el medio del piso para satisfacer a las ratas para que no masticaran la tela por su hambre y regresaba a casa. Allí leía del Caitanya-caritāmṛta y del Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, las principales escrituras de los vaiṣṇavas bengalíes, rezaba en sus cuentas de japa y adoraba a la Deidad del Señor Kṛṣṇa. Era gentil y cariñoso, nunca castigó a Abhay. Incluso cuando estuvo obligado a corregirlo, Gour Mohan primero se disculpaba: Eres mi hijo, así que ahora debo corregirte. Es mi deber. Incluso el padre de Caitanya Mahāprabhu Lo castigaba, así que no te molestes.

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda: My father’s income was no more than 250 rupees, but there was no question of need. In the mango season when we were children, we would run through the house playing, and we would grab mangoes as we were running through. And all through the day we would eat mangoes. We wouldn’t have to think, “Can I have a mango?” My father always provided food – mangoes were one rupee a dozen.

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda: Los ingresos de mi padre no superaban las 250 rupias, pero no había carencias. En la temporada del mango cuando éramos niños, corríamos por la casa jugando y agarrábamos mangos mientras corríamos. Comíamos mangos durante todo el día. No teníamos que pensar: “¿Puedo tener un mango?” Mi padre siempre proporcionaba comida: los mangos costaban una rupia la docena.

|  | Life was simple, but there was always plenty. We were middle class but receiving four or five guests daily. My father gave four daughters in marriage, and there was no difficulty for him. Maybe it was not a very luxurious life, but there was no scarcity of food or shelter or cloth. Daily he purchased two and a half kilograms of milk. He did not like to purchase retail but would purchase a year’s supply of coal by the cartload.

| | La vida era sencilla, pero siempre había abundancia. Éramos de clase media pero recibíamos a cuatro o cinco invitados al día. Mi padre dio cuatro hijas en matrimonio y no hubo dificultad para él. Tal vez no era una vida muy lujosa, pero no había escasez de comida, techo o ropa. Diariamente compraba dos kilos y medio de leche. No le gustaba comprar al por menor, compraría el suministro de carbón para un año por carretadas.

|  | We were happy – not that because we did not purchase a motorcar we were unhappy. My father used to say, God has ten hands. If He wants to take away from you, with two hands how much can you protect? And when He wants to give to you with ten hands, then with your two hands how much can you take?

| | Éramos felices; no porque no compráramos un automóvil, no eramos felices. Mi padre solía decir: Dios tiene diez manos. Si Él quiere quitarte algo, ¿con dos manos cuánto puedes proteger? Y cuando Él quiere darte con diez manos, entonces ¿con tus dos manos cuánto puedes tomar?

|  | My father would rise a little late, around seven or eight. Then, after taking bath, he would go purchasing. Then, from ten o’clock to one in the afternoon, he was engaged in pūjā. Then he would take his lunch and go to business. And in the business shop he would take a little rest for one hour. He would come home from business at ten o’clock at night, and then again he would do pūjā. Actually, his real business was pūjā. For livelihood he did some business, but pūjā was his main business. We would be sleeping, and father would be doing ārati. Ding ding ding – we would hear the bell and wake up and see him bowing down before Kṛṣṇa.

| | Mi padre se levantaba un poco tarde, alrededor de las siete u ocho. Después de bañarse, iba de compras, desde las diez en punto hasta la una de la tarde, estaba ocupado en la pūjā. Luego tomaba su almuerzo e iba a los negocios. En la tienda de negocios descansaba un poco por una hora. Llegaba a casa del negocio a las diez de la noche y volvía a hacer pūjā. En realidad, su verdadera ocupación era la pūjā. Para ganarse la vida hizo algunos negocios, pero la pūjā era su ocupación principal. Estabamos durmiendo y papá estaba haciendo ārati. Ding ding ding: escuchamos la campana, nos despertabamos y lo veíamos inclinarse ante Kṛṣṇa.

|  | Gour Mohan wanted Vaiṣṇava goals for his son; he wanted Abhay to become a servant of Rādhārāṇī, to become a preacher of the Bhāgavatam, and to learn the devotional art of playing mṛdaṅga. He regularly received sādhus in his home, and he would always ask them, “Please bless my son so that Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī may be pleased with him and grant him Her blessings.”

| | Gour Mohan tenía objetivos vaiṣṇavas para su hijo; quería que Abhay se convirtiera en un sirviente de Rādhārāṇī, que se convirtiera en un predicador del Bhāgavatam y que aprendiera el arte devocional de tocar mṛdaṅga. Regularmente recibía sadhus en su casa y siempre les pedía: “Por favor, bendiga a mi hijo para que Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī esté complacida con él y le conceda Sus bendiciones”.

|  | Enjoying each other’s company, father and son used to walk as far as ten miles (16 km), saving the five-paisa tram fare. On the beach they used to see a yogī who for years had sat in one spot without moving. One day the yogī’s son was sitting there, and people had gathered around; the son was taking over his father’s sitting place. Gour Mohan gave the yogīs a donation and asked their blessings for his son.

| | Disfrutando de la compañía del otro, padre e hijo solían caminar hasta dieciséis kilómetros, ahorrándose el boleto de cinco paisas del tranvía. En la playa solían ver a un yoguī que durante años se sentó en un lugar sin moverse. Un día, el hijo del yoguī estaba sentado allí y la gente se reunió alrededor; el hijo estaba ocupando el lugar donde se sentaba su padre. Gour Mohan hizo una donación a los yoguīs y les pidió bendiciones para su hijo.

|  | When Abhay’s mother said she wanted him to become a British lawyer when he grew up (which meant he would have to go to London to study), one of the Mullik “uncles” thought it was a good idea. But Gour Mohan would not hear of it; if Abhay went to England he would be influenced by European dress and manners. He will learn drinking and women-hunting, Gour Mohan objected. I do not want his money.

| | Cuando la madre de Abhay dijo que quería que él se convirtiera en abogado británico cuando creciera (lo que significaba que tendría que ir a Londres a estudiar), uno de los “tíos” de Mullik pensó que era una buena idea. Pero Gour Mohan no quiso ni oír hablar de ello; si Abhay va a Inglaterra, estaría influenciado por la vestimenta y los modales europeos. Aprenderá a beber y a cazar mujeres, objetó Gour Mohan. No quiero su dinero.

|  | From the beginning of Abhay’s life, Gour Mohan had introduced his plan. He had hired a professional mṛdaṅga player to teach Abhay the standard rhythms for accompanying kīrtana. Rajani had been skeptical: What is the purpose of teaching such a young child to play the mṛdaṅga? It is not important. But Gour Mohan had his dream of a son who would grow up singing bhajans, playing mṛdaṅga, and speaking on Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam.

| | Desde el comienzo de la vida de Abhay, Gour Mohan introdujo su plan. Contrató a un músico profesional de mṛdaṅga para que le enseñara a Abhay los ritmos estándares para acompañar el kīrtana. Rajani se mostró escéptico: ¿Cuál es el propósito de enseñar a un niño tan pequeño a tocar la mṛdaṅga? No es importante. Pero Gour Mohan soñaba con un hijo que crecería cantando bhajans, tocando mṛdaṅga y hablando sobre el Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam.

|  | When Abhay sat to play the mṛdaṅga, even with his left and right arms extended as far as he could, his small hands would barely reach the drumheads at the opposite ends of the drum. With his right wrist he would flick his hand just as his teacher instructed, and his fingers would make a high-pitched sound – tee nee tee nee taw – and then he would strike the left drumhead with his open left hand – boom boom. With practice and age he was gradually learning the basic rhythms, and Gour Mohan looked on with pleasure.

| | Cuando Abhay se sentaba a tocar la mṛdaṅga, incluso con los brazos izquierdo y derecho extendidos tanto como podía, sus pequeñas manos apenas alcanzaban los parches en los extremos opuestos del tambor. Con la muñeca derecha, movía la mano tal como le indicaba su maestro y sus dedos hacían un sonido agudo: tee nee tee nee taw, luego golpeaba el parche izquierdo con la mano izquierda abierta: boom boom. Con la práctica y la edad fue aprendiendo poco a poco los ritmos básicos, Gour Mohan lo miraba con placer.

|  | Abhay was an acknowledged pet child of both his parents. In addition to his childhood names Moti, Nandulal, Nandu, and Kocha, his grandmother called him Kacaurī-mukhī because of his fondness for kacaurīs (spicy, vegetable-stuffed fried pastries, popular in Bengal). Both his grandmother and mother would give him kacaurīs, which he kept in the many pockets of his little vest. He liked to watch the vendors cooking on the busy roadside and accept kacaurīs from them and from the neighbors, until all the inside and outside pockets of his vest were filled.

| | Abhay fue un hijo consentido por sus padres. Además de sus nombres de infancia Moti, Nandulal, Nandu y Kocha, su abuela lo llamó Kacaurī-mukhī debido a su afición por los kacaurīs (pasteles fritos muy condimentados rellenos de vegetales, populares en Bengala). Tanto su abuela como su madre le regalaban kacaurīs, que guardaba en los múltiples bolsillos de su pequeño chaleco. Le gustaba ver a los vendedores cocinar en la concurrida calle y aceptar kacaurīs de ellos y de los vecinos, hasta llenar todos los bolsillos interiores y exteriores de su chaleco.

|  | Sometimes when Abhay demanded that his mother make him kacaurīs, she would refuse. Once she even sent him to bed. When Gour Mohan came home and asked, Where is Abhay? Rajani explained how he had been too demanding and she had sent him to bed without kacaurīs. No, we should make them for him, his father replied, and he woke Abhay and personally cooked purīs and kacaurīs for him. Gour Mohan was always lenient with Abhay and careful to see that his son got whatever he wanted. When Gour Mohan returned home at night, it was his practice to take a little puffed rice, and Abhay would also sometimes sit with his father, eating puffed rice.

| | A veces, cuando Abhay exigía que su madre le hiciera kacaurīs, ella se negaba. Una vez incluso lo mandó a la cama. Cuando Gour Mohan llegó a casa y preguntó: ¿Dónde está Abhay?, Rajani explicó que él fue demasiado exigente y que ella lo envió a la cama sin kacaurīs. No, debemos prepararlos para él, respondió su padre, despertó a Abhay y personalmente le preparó purīs y kacaurīs. Gour Mohan siempre fue indulgente con Abhay y se aseguró de que su hijo obtuviera todo lo que quería. Cuando Gour Mohan regresaba a casa por la noche, era su práctica tomar un poco de arroz inflado, a veces, Abhay también se sentaba con su padre a comer arroz inflado.

|  | Once, at a cost of six rupees, Gour Mohan bought Abhay a pair of shoes imported from England. And each year, through a friend who traveled back and forth from Kashmir, Gour Mohan would present his son a Kashmiri shawl with a fancy, hand-sewn border.

| | Una vez, a un costo de seis rupias, Gour Mohan le compró a Abhay un par de zapatos importados de Inglaterra. Y cada año, a través de un amigo que viajaba de un lado a otro de Cachemira, Gour Mohan le regalaba a su hijo un chal de Cachemira con un elegante borde cosido a mano.

|  | One day in the market, Abhay saw a toy gun he wanted. His father said no, and Abhay started to cry. All right, all right, Gour Mohan said, and he bought the gun. Then Abhay wanted another gun. You already have one, his father said. Why do you want another one?

| | Un día en el mercado, Abhay vio una pistola de juguete que quería. Su padre dijo que no y Abhay comenzó a llorar. Está bien, está bien, dijo Gour Mohan y compró el arma. Entonces Abhay quiso otra arma. Ya tienes una, dijo su padre. ¿Por qué quieres otra?

|  | One for each hand, Abhay cried, and he lay down in the street, kicking his feet. When Gour Mohan agreed to get the second gun, Abhay was pacified.

| | Una para cada mano, gritó Abhay y se tumbó en la calle, pataleando. Cuando Gour Mohan accedió a comprar la segunda arma, Abhay se tranquilizó.

|  | Abhay’s mother, Rajani, was thirty years old when he was born. Like her husband, she came from a long-established Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava family. She was darker-skinned than her husband, and whereas his disposition was cool, hers tended to be fiery. Abhay saw his mother and father living together peacefully; no deep marital conflict or complicated dissatisfaction ever threatened home. Rajani was chaste and religious-minded, a model housewife in the traditional Vedic sense, dedicated to caring for her husband and children. Abhay observed his mother’s simple and touching attempts to insure, by prayers, by vows, and even by rituals, that he continue to live. Whenever he was to go out even to play, his mother, after dressing him, would put a drop of saliva on her finger and touch it to his forehead. Abhay never knew the significance of this act, but because she was his mother he stood submissively “like a dog with its master” while she did it.

| | La madre de Abhay, Rajani, tenía treinta años cuando él nació. Al igual que su esposo, ella provenía de una familia Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava establecida desde hace mucho tiempo. Ella tenía la piel más oscura que su marido, mientras que la disposición de él era tranquila, la de ella tendía a ser fogosa. Abhay vio a su madre y a su padre viviendo juntos en paz; ningún conflicto marital profundo o insatisfacción complicada amenazó jamás el hogar. Rajani fue casta y de mente religiosa, una ama de casa modelo en el sentido védico tradicional, dedicada al cuidado de su esposo e hijos. Abhay observó los intentos sencillos y conmovedores de su madre para asegurar, mediante oraciones, votos e incluso rituales, que él continuara con vida. Siempre que salía aunque fuera a jugar, su madre, después de vestirlo, le ponía una gota de saliva en el dedo y le tocaba la frente con ella. Abhay nunca supo el significado de este acto, pero como ella era su madre, permaneció sumiso “como un perro con su amo” mientras ella lo hacía.

|  | Like Gour Mohan, Rajani treated Abhay as the pet child; but whereas her husband expressed his love through leniency and plans for his son’s spiritual success, she expressed hers through attempts to safeguard Abhay from all danger, disease, and death. She once offered blood from her breast to one of the demigods with the supplication that Abhay be protected on all sides from danger.

| | Al igual que Gour Mohan, Rajani trató a Abhay como un niño mimado; pero mientras que su esposo expresó su amor a través de la indulgencia y los planes para el éxito espiritual de su hijo, ella expresó el suyo a través de los intentos de salvaguardar a Abhay de todo peligro, enfermedad y muerte. Una vez ofreció sangre de su pecho a uno de los semidioses con la súplica de que Abhay fuera protegido por todos lados del peligro.

|  | At Abhay’s birth, she had made a vow to eat with her left hand until the day her son would notice and ask her why she was eating with the wrong hand. One day, when little Abhay actually asked, she immediately stopped. It had been just another prescription for his survival, for she thought that by the strength of her vow he would continue to grow, at least until he asked her about the vow. Had he not asked, she would never again have eaten with her right hand, and according to her superstition he would have gone on living, protected by her vow.

| | Cuando nació Abhay, ella hizo la promesa de comer con la mano izquierda hasta el día en que su hijo se diera cuenta y le preguntara por qué estaba comiendo con la mano equivocada. Un día, cuando el pequeño Abhay directamente le preguntó, ella dejó de hacerlo de inmediato. Esta fue solo otra receta para su supervivencia, porque ella pensaba que por la fuerza de su voto él seguiría creciendo, al menos hasta que le preguntara sobre el voto. Si él no se lo hubiera preguntado, ella nunca más habría comido con su mano derecha y según su superstición, él habría seguido viviendo protegido por su voto.

|  | For his protection she also put an iron bangle around his leg. His playmates asked him what it was, and Abhay self-consciously went to his mother and demanded, “Open this bangle!” When she said, “I will do it later,” he began to cry, “No, now!” Once Abhay swallowed a watermelon seed, and his friends told him it would grow in his stomach into a watermelon. He ran to his mother, who assured him he didn’t have to worry; she would say a mantra to protect him.

| | Para su protección, también le puso un brazalete de hierro alrededor de la pierna. Sus compañeros de juego le preguntaron qué era, Abhay conscientemente fue hacia su madre y le exigió: “¡Abre este brazalete!”. Cuando ella dijo: “Lo haré más tarde”, él comenzó a llorar: “¡No, ahora!”. Una vez, Abhay se tragó una semilla de sandía y sus amigos le dijeron que crecería en su estómago hasta convertirse en una sandía. Corrió hacia su madre, quien le aseguró que no tenía por qué preocuparse; ella diría un mantra para protegerlo.

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda: Mother Yaśodā would chant mantras in the morning to protect Kṛṣṇa from all dangers throughout the day. When Kṛṣṇa killed some demon she thought it was due to her chanting. My mother would do a similar thing with me.

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda: Madre Yaśodā cantaba mantras por la mañana para proteger a Kṛṣṇa de todos los peligros durante el día. Cuando Kṛṣṇa mató a algún demonio, ella pensó que se debía a su canto. Mi madre hizo algo similar conmigo.

|  | His mother would often take him to the Ganges and personally bathe him. She also gave him a food supplement known as Horlicks. When he got dysentery, she cured it with hot purīs and fried eggplant with salt, though sometimes when he was ill Abhay would show his obstinacy by refusing to take any medicine. But just as he was stubborn, his mother was determined, and she would forcibly administer medicine into his mouth, though sometimes it took three assistants to hold him down.

| | Su madre lo llevaba a menudo al Ganges y lo bañaba personalmente. También le dio un complemento alimenticio conocido como Horlicks. Cuando le dio disentería, ella se la curó con purīs calientes y berenjenas fritas con sal, aunque a veces, cuando estaba enfermo, Abhay mostraba su obstinación negándose a tomar algún medicamento. Pero así como él era obstinado, su madre estaba decidida y le administraba los medicamentos a la fuerza en la boca, aunque a veces se necesitaban tres asistentes para sujetarlo.

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda: I was very naughty when I was a boy. I would break anything. When I was angry, I would break the glass hookah pipes, which my father kept to offer to guests. Once my mother was trying to bathe me, and I refused and knocked my head on the ground, and blood came out. They came running and said, “What are you doing? You shall kill the child.”

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda: Yo era muy travieso cuando era niño. Rompía cualquier cosa. Cuando estaba enojado, rompía las pipas de vidrio para narguiles que mi padre guardaba para ofrecer a los invitados. Una vez mi madre trataba de bañarme, me negué y golpeé mi cabeza contra el suelo y salió sangre. Vinieron corriendo y le dijeron: “¿Qué estás haciendo? Matarás al niño.”

|  | Abhay was present when his mother observed the ceremony of Sādha-hotra during the seventh and ninth months of her pregnancies. Freshly bathed, she would appear in new clothing along with her children and enjoy a feast of whatever foods she desired, while her husband gave goods in charity to the local brāhmaṇas, who chanted mantras for the purification of the mother and the coming child.

| | Abhay estuvo presente cuando su madre observó la ceremonia de Sādha-hotra durante el séptimo y noveno mes de su embarazo. Recién bañada, aparecía con ropa nueva junto con sus hijos y disfrutaba de un festín de los alimentos que deseaba, mientras su esposo daba bienes en caridad a los brāhmaṇas locales, quienes cantaban mantras para la purificación de la madre y el niño que estaba por nacer.

|  | Abhay was completely dependent on his mother. Sometimes she would put his shirt on backwards, and he would simply accept it without mentioning it. Although he was sometimes stubborn, he felt dependent on the guidance and reassurance of his mother. When he had to go to the privy, he would jump up and down beside her, holding her sārī and saying, Urine, mother, urine.

| | Abhay dependía completamente de su madre. A veces ella le ponía la camisa al revés y él simplemente lo aceptaba sin mencionarlo. Aunque a veces era terco, se sentía dependiente de la guía y el consuelo de su madre. Cuando tenía que ir al retrete, saltaba arriba y abajo junto a ella, tomándola de su sārī y diciendo: Orina, madre, orina.

|  | Who is stopping you? she would ask. Yes, you can go. Only then, with her permission, would he go.

| | ¿Quién te detiene? Preguntaba ella. Sí, puedes ir. Sólo entonces, con su permiso, él iba.

|  | Sometimes, in the intimacy of dependence, his mother became his foil. When he lost a baby tooth and on her advice placed it under a pillow that night, the tooth vanished, and some money appeared. Abhay gave the money to his mother for safekeeping, but later, when in their constant association she opposed him, he demanded, I want my money back! I will go away from home. Now you give me my money back!

| | A veces, en la intimidad de la dependencia, su madre se convertía en su contraste. Cuando perdió un diente de leche y siguiendo el consejo de ella, lo colocó debajo de una almohada esa noche, el diente desapareció y apareció algo de dinero. Abhay le dio el dinero a su madre para que lo guardara, pero más tarde, cuando en su constante asociación ella se opuso a él, exigió: ¡Quiero que me devuelvas mi dinero! me iré de casa. ¡Ahora devuélveme mi dinero!

|  | When Rajani wanted her hair braided, she would regularly ask her daughters. But if Abhay were present he would insist on braiding it himself and would create such a disturbance that they would give in to him. Once he painted the bottoms of his feet red, imitating the custom of women who painted their feet on festive occasions. His mother tried to dissuade him, saying it was not for children, but he insisted, No, I must do it, also!

| | Cuando Rajani quería que le trenzaran el pelo, se lo pedía regularmente a sus hijas. Pero si Abhay estaba presente, insistía en trenzarlo él mismo y creaba tal alboroto que se rendían ante él. Una vez se pintó las plantas de los pies de rojo, imitando la costumbre de las mujeres que se pintaban los pies en ocasiones festivas. Su madre trató de disuadirlo diciéndole que no era para niños, pero él insistió: No, ¡también yo debo hacerlo!

|  | Abhay was unwilling to go to school. Why should I go? he thought. I will play all day. When his mother complained to Gour Mohan, Abhay, sure that his father would be affectionate, said, No, I shall go tomorrow.

| | Abhay no estaba dispuesto a ir a la escuela. ¿Por qué debo ir? pensó. Jugaré todo el día. Cuando su madre se quejó con Gour Mohan, Abhay, seguro de que su padre sería cariñoso, dijo: No, iré mañana.

|  | All right, he will go tomorrow, said Gour Mohan. That’s all right. But the next morning Abhay complained that he was sick, and his father indulged him.

| | Está bien, irá mañana, dijo Gour Mohan. Está bien. Pero a la mañana siguiente, Abhay se quejó de estar enfermo y su padre lo toleró.

|  | Rajani became upset because the boy would not go to school, and she hired a man for four rupees to escort him there. The man, whose name was Damodara, would tie Abhay about the waist with a rope – a customary treatment – take him to school, and present him before his teacher. When Abhay would try to run away, Damodara would pick him up and carry him in his arms. After being taken a few times by force, Abhay began to go on his own.

| | Rajani se molestó porque el niño no iba a la escuela y contrató a un hombre por cuatro rupias para que lo acompañara hasta allí. El hombre, cuyo nombre era Damodara, ataba a Abhay por la cintura con una cuerda, un trato habitual, lo llevaba a la escuela y lo presentaba ante su maestro. Cuando Abhay intentaba huir, Damodara lo levantaba y lo cargaba en sus brazos. Después de ser llevado a la fuerza varias veces, Abhay comenzó a ir por su cuenta.

|  | Abhay proved an attentive, well-behaved student, though sometimes he was naughty. Once when the teacher pulled his ear, Abhay threw a kerosene lantern to the floor, accidentally starting a fire.

| | Abhay demostró ser un estudiante atento y de buen comportamiento, aunque a veces era travieso. Una vez, cuando el maestro le jaló la oreja, Abhay arrojó una lámpara de queroseno al piso, provocando un incendio accidentalmente.

|  | In those days any common villager, even if illiterate, could recite from the Rāmāyaṇa, Mahābhārata, or Bhāgavatam. Especially in the villages, everyone would assemble in the evening to hear from these scriptures. It was for this purpose that Abhay’s family would sometimes go in the evening to his maternal uncle’s house, about ten miles (16 km) away, where they would assemble and hear about the Lord’s transcendental pastimes. They would return home discussing and remembering them and then go to bed and dream Rāmāyaṇa, Mahābhārata, and Bhāgavatam.

| | En aquellos días, cualquier aldeano común, incluso si era analfabeto, podía recitar el Rāmāyaṇa, el Mahābhārata o el Bhāgavatam. Especialmente en las aldeas, todos se reunían por la noche para escuchar estas escrituras. Era con este propósito que la familia de Abhay a veces iba por la noche a la casa de su tío materno, a unos dieciseis kilómetros de distancia, donde se reunían y escuchaban acerca de los pasatiempos trascendentales del Señor. Regresaban a casa disertándolos y recordándolos, luego se iban a la cama y soñaban sobre el Rāmāyaṇa, el Mahābhārata y el Bhāgavatam.

|  | After his afternoon rest and bath, Abhay would often go to a neighbor’s house and look at the black-and-white pictures in Mahābhārata. His grandmother asked him daily to read Mahābhārata from a vernacular edition. Thus by looking at pictures and reading with his grandmother, Abhay imbibed Mahābhārata.

| | Después de su descanso y baño de la tarde, Abhay solía ir a la casa de un vecino y mirar las imágenes en blanco y negro del Mahābhārata. Su abuela le pedía diariamente que leyera el Mahābhārata de una edición vernácula. Así, mirando imágenes y leyendo con su abuela, Abhay absorbió el Mahābhārata.

|  | In Abhay’s childhood play, his younger sister Bhavatarini was often his assistant. Together they would go to see the Rādhā-Govinda Deities in the Mulliks’ temple. In their play, whenever they encountered obstacles, they would pray to God for help. “Please, Kṛṣṇa, help us fly this kite,” they would call as they ran along trying to put their kite into flight.

| | En la obra de teatro infantil de Abhay, su hermana menor, Bhavatarini, solía ser su asistente. Juntos iban a ver las Deidades de Rādhā-Govinda en el templo de los Mullik. En su juego, cada vez que encontraban obstáculos, rezaban a Dios para pedir ayuda. “Por favor, Kṛṣṇa, ayúdanos a volar esta cometa”, gritaban mientras corrían tratando de ponerla en vuelo.

|  | Abhay’s toys included two guns, a wind-up car, a cow that jumped when Abhay squeezed the rubber bulb attached, and a dog with a mechanism that made it dance. The toy dog was from Dr. Bose, the family physician, who gave it to him when treating a minor wound on Abhay’s side. Abhay sometimes liked to pretend that he was a doctor, and to his friends he would administer “medicine,” which was nothing more than dust.

| | Los juguetes de Abhay incluían dos pistolas, un coche de cuerda, una vaca que saltaba cuando Abhay apretaba la perilla de goma que se le había acoplado y un perro con un mecanismo que lo hacía bailar. El perro de juguete era del Dr. Bose, el médico de la familia, quien se lo dio cuando trataba una herida menor en el costado de Abhay. A Abhay a veces le gustaba fingir que era médico y a sus amigos les administraba “medicina”, que no era más que polvo.

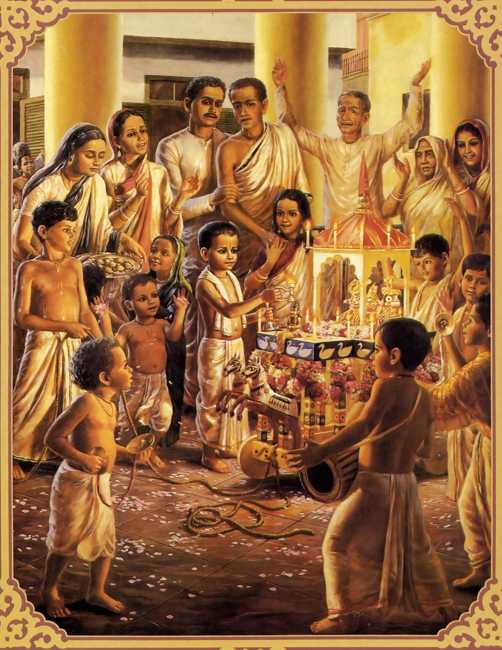

|  | Abhay was enamored with the Ratha-yātrā festivals of Lord Jagannātha, held yearly in Calcutta. The biggest Calcutta Ratha-yātrā was the Mulliks’, with three separate carts bearing the deities of Jagannātha, Baladeva, and Subhadrā. Beginning from the Rādhā-Govinda temple, the carts would proceed down Harrison Road for a short distance and then return. The Mulliks would distribute large quantities of Lord Jagannātha’s prasādam to the public on this day.

| | Abhay estaba enamorado de los festivales de Ratha-yātrā del Señor Jagannātha, que se celebran anualmente en Calcuta. El Ratha-yātrā más grande de Calcutta era el de los Mullik, con tres carros separados que llevaban las deidades de Jagannātha, Baladeva y Subhadrā. Comenzando desde el templo de Rādhā-Govinda, los carros continuaban por la Calle Harrison por una corta distancia y luego regresaban. Los Mullik distribuirían ese día al público grandes cantidades de prasādam del Señor Jagannātha.

|  | Ratha-yātrā was held in cities all over India, but the original, gigantic Ratha-yātrā, attended each year by millions of pilgrims, took place three hundred miles (480 km) south of Calcutta at Jagannātha Purī. For centuries at Purī, three wooden carts forty-five feet (13 m) high had been towed by the crowds along the two-mile (3.2 km) parade route, in commemoration of one of Lord Kṛṣṇa’s eternal pastimes. Abhay had heard how Lord Caitanya Himself, four hundred years before, had danced and led ecstatic chanting of Hare Kṛṣṇa at the Purī Ratha-yātrā festival. Abhay would sometimes look at the railway timetable or ask about the fare to Vṛndāvana and Purī, thinking about how he would collect the money and go there.

| | El Ratha-yātrā se lleva a cabo en ciudades de toda la India, pero el original y gigantesco Ratha-yātrā, al que asisten cada año millones de peregrinos, se lleva a cabo a cuatreocientos ochenta kilómetros al sur de Calcuta en Jagannātha Purī. Durante siglos en Purī, la multitud remolca tres carretas de madera de trece metros de altura a lo largo de la ruta del desfile de poco más de tres kilómetros, en conmemoración de uno de los pasatiempos eternos del Señor Kṛṣṇa. Abhay escuchó cómo el propio Señor Caitanya, cuatrocientos años antes, bailó y dirigió el canto extático de Hare Kṛṣṇa en el festival del Ratha-yātrā de Purī. A veces Abhay miraba el horario del tren o preguntaba sobre el viaje a Vṛndāvana y Purī, pensando en cómo recolectar el dinero e ir allí.

|  | Abhay wanted to have his own cart and to perform his own Ratha-yātrā, and naturally he turned to his father for help. Gour Mohan agreed, but there were difficulties. When he took his son to several carpenter shops, he found that he could not afford to have a cart made. On their way home, Abhay began crying, and an old Bengali woman approached and asked him what the matter was. Gour Mohan explained that the boy wanted a Ratha-yātrā cart but they couldn’t afford to have one made. Oh, I have a cart, the woman said, and she invited Gour Mohan and Abhay to her place and showed them the cart. It looked old, but it was still operable, and it was just the right size, about three feet (1 m) high. Gour Mohan purchased it and helped to restore and decorate it. Father and son together constructed sixteen supporting columns and placed a canopy on top, resembling as closely as possible the ones on the big carts at Purī. They also attached the traditional wooden horse and driver to the front of the cart. Abhay insisted that it must look authentic. Gour Mohan bought paints, and Abhay personally painted the cart, copying the Purī originals. His enthusiasm was great, and he became an insistent organizer of various aspects of the festival. But when he tried making fireworks for the occasion from a book that gave illustrated descriptions of the process, Rajani intervened.

| | Abhay quería tener su propio carro y realizar su propio Ratha-yātrā, naturalmente, recurrió a su padre en busca de ayuda. Gour Mohan estuvo de acuerdo, pero hubo dificultades. Cuando llevó a su hijo a varios talleres de carpintería, descubrió que no podía permitirse el lujo de hacer un carro. De camino a casa, Abhay empezó a llorar, una anciana bengalí se le acercó y le preguntó qué le pasaba. Gour Mohan explicó que el niño quería un carro de Ratha-yātrā pero que no podían permitirse el lujo de hacerlo. Oh, yo tengo un carro, dijo la mujer, e invitó a Gour Mohan y a Abhay a donde lo guardaba para mostrarles el carro. Parecía viejo, pero aún funcionaba y tenía el tamaño justo, aproximadamente un metro de altura. Gour Mohan lo compró, ayudó a restaurarlo y decorarlo. Padre e hijo juntos construyeron dieciséis columnas de soporte y colocaron un dosel en la parte superior, pareciéndose lo más posible a las de los grandes carros en Purī. También colocaron el tradicional caballo de madera y al conductor en la parte delantera del carro. Abhay insistió en que debía parecer auténtico. Gour Mohan compró pinturas y Abhay pintó personalmente el carrito, copiando los originales de Purī. Su entusiasmo era grande y se convirtió en un organizador insistente de varios aspectos del festival. Pero cuando intentó hacer fuegos artificiales para la ocasión a partir de un libro que brindaba descripciones ilustradas del proceso, intervino Rajani.

|  | Abhay engaged his playmates in helping him, especially his sister Bhavatarini, and he became their natural leader. Responding to his entreaties, amused mothers in the neighborhood agreed to cook special preparations so that he could distribute the prasādam at his Ratha-yātrā festival.

| | Abhay involucró a sus compañeros de juegos para que lo ayudaran, especialmente a su hermana Bhavatarini, se convirtió en su líder natural. Respondiendo a sus súplicas, las divertidas madres del vecindario acordaron cocinar preparaciones especiales para que él pudiera distribuir el prasādam en su festival de Ratha-yātrā.

|  | Like the festival at Purī, Abhay’s Ratha-yātrā ran for eight consecutive days. His family members gathered, and the neighborhood children joined in a procession, pulling the cart, playing drums and karatālas, and chanting. Wearing a dhotī and no shirt in the heat of summer, Abhay led the children in chanting Hare Kṛṣṇa and in singing the appropriate Bengali bhajana, Ki kara rāi kamalinī.

| | Al igual que el festival de Purī, el Ratha-yātrā de Abhay duró ocho días consecutivos. Los miembros de su familia se reunieron y los niños del vecindario se unieron en una procesión, tirando del carro, tocando tambores, karatālas y cantando. Vistiendo un dhotī y sin camisa en el calor del verano, Abhay dirigió a los niños en el canto de Hare Kṛṣṇa y en el canto del bhajana bengalí apropiado, Ki kara rāi kamalinī.

|  | What are You doing, Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī?

Please come out and see.

They are stealing Your dearmost treasure –

Kṛṣṇa, the black gem.

If the young girl only knew!

The young boy Kṛṣṇa,

Treasure of Her heart,

Is now forsaking Her.

| | ¿Qué estás haciendo, Śrīmatī Rādhārāṇī?

Por favor, sal y mira.

Están robando Tu tesoro más querido –

Kṛṣṇa, la gema negra.

¡Si la joven lo supiera!

El joven Kṛṣṇa,

Tesoro de Su corazón,

ahora la está abandonando.

|  | Abhay copied whatever he had seen at adult religious functions, including dressing the deities, offering the deities food, offering ārati with a ghī lamp and incense, and making prostrated obeisances. From Harrison Road the procession entered the circular road inside the courtyard of the Rādhā-Govinda temple and stood awhile before the Deities. Seeing the fun, Gour Mohan’s friends approached him: Why haven’t you invited us? You are holding a big ceremony, and you don’t invite us? What is this?

| | Abhay copió todo lo que había visto en las funciones religiosas para adultos, incluido el vestir a las deidades, ofrecerles comida a las deidades, ofrecer ārati con una lámpara de ghī e incienso y hacer reverencias postradas. Desde la Calle Harrison, la procesión entró en el camino circular dentro del patio del templo de Rādhā-Govinda y se detuvo un rato ante las Deidades. Al ver la diversión, los amigos de Gour Mohan se le acercaron: ¿Por qué no nos has invitado? ¿Vas a celebrar una gran ceremonia y no nos invitas? ¿Qué es esto?

|  | They are just children playing, his father replied.

Oh, children playing? the men joked. You are depriving us by saying that this is only for children?

| | Son solo niños jugando, respondió su padre.

Oh, ¿niños jugando? bromearon los hombres. ¿Nos estás privando al decir que esto es solo para niños?

|  | While Abhay was ecstatically absorbed in the Ratha-yātrā processions, Gour Mohan spent money for eight consecutive days, and Rajani cooked various dishes to offer, along with flowers, to Lord Jagannātha. Although everything Abhay did was imitation, his inspiration and steady drive for holding the festival were genuine. His spontaneous spirit sustained the eight-day children’s festival, and each successive year brought a new festival, which Abhay would observe in the same way.

| | Mientras Abhay estaba absorto en éxtasis en las procesiones del Ratha-yātrā, Gour Mohan gastó dinero durante ocho días consecutivos y Rajani cocinó varios platos para ofrecer, junto con flores, al Señor Jagannātha. Aunque todo lo que hizo Abhay fue una imitación, su inspiración y firme impulso para celebrar el festival fueron genuinos. Su espíritu espontáneo sostuvo el festival infantil de ocho días y cada año sucesivo trajo un nuevo festival, que Abhay observó de la misma manera.

|  | When Abhay was about six years old, he asked his father for a Deity of his own to worship. Since infancy he had watched his father doing pūjā at home and had been regularly seeing the worship of Rādhā-Govinda and thinking, When will I be able to worship Kṛṣṇa like this? On Abhay’s request, his father purchased a pair of little Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa Deities and gave Them to him. From then on, whatever Abhay ate he would first offer to Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa, and imitating his father and the priests of Rādhā-Govinda, he would offer his Deities a ghī lamp and put Them to rest at night.

| | Cuando Abhay tenía unos seis años, le pidió a su padre unas Deidades propias para adorar. Desde la infancia vió a su padre hacer pūjā en casa, asistió regularmente a la adoración de Rādhā-Govinda y pensó: ¿Cuándo podré adorar a Kṛṣṇa de esta manera? A pedido de Abhay, su padre compró un par de pequeñas Deidades de Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa y se las dio. A partir de ese momento, todo lo que Abhay comía lo ofrecía primero a Rādhā y Kṛṣṇa, e imitando a su padre y a los sacerdotes de Rādhā-Govinda, ofrecía a sus Deidades una lámpara de ghī y las ponía a descansar por la noche.

|  | Abhay and his sister Bhavatarini became dedicated worshipers of the little Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa Deities, spending much of their time dressing and worshiping Them and sometimes singing bhajanas. Their brothers and sisters laughed, teasing Abhay and Bhavatarini by saying that because they were more interested in the Deity than in their education they would not live long. But Abhay replied that they didn’t care.

| | Abhay y su hermana Bhavatarini se convirtieron en adoradores dedicados de las pequeñas Deidades de Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa, pasando gran parte de su tiempo vistiéndolas, adorándolas y algunas veces cantando bhajanas. Sus hermanos y hermanas se reían, burlándose de Abhay y Bhavatarini diciendo que debido a que estaban más interesados en la Deidad que en su educación, no vivirían mucho tiempo. Pero Abhay respondió que no les importaba eso.

|  | Once a neighbor asked Abhay’s mother, How old is your little son?

| | Una vez, un vecino le preguntó a la madre de Abhay: ¿Qué edad tiene su hijo pequeño?

|  | He’s seven, she said, as Abhay listened with interest. He had never heard anyone discuss his age before; but now he understood for the first time: I am seven.

| | Tiene siete años, dijo, mientras Abhay escuchaba con interés. Nunca antes había escuchado a nadie hablar sobre su edad; pero ahora entendió por primera vez: Tengo siete años.

|  | In addition to the education Abhay received at the kindergarten to which he had at first been forcibly dragged, he also received private tutoring at home from his fifth year to his eighth. He learned to read Bengali and began learning Sanskrit. Then in 1904, when he was eight years old, Abhay entered the nearby Mutty Lall Seal Free School, on the corner of Harrison and Central roads.

| | Además de la educación que Abhay recibió en el jardín de infancia al que primero lo arrastraron a la fuerza, también recibió clases privadas en su casa desde el quinto hasta el octavo año. Aprendió a leer bengalí y comenzó a aprender sánscrito. Luego, en 1904, cuando tenía ocho años, Abhay ingresó a la cercana Mutty Lall Seal Free School, en la esquina de las calles Harrison y Central.

|  | Mutty Lall was a boys’ school founded in 1842 by a wealthy suvarṇa-vaṇik Vaiṣṇava. The building was stone, two stories, and surrounded by a stone wall. The teachers were Indian, and the students were Bengalis from local suvarṇa-vaṇik families. Dressed in their dhotīs and kurtās, the boys would leave their mothers and fathers in the morning and walk together in little groups, each boy carrying a few books and his tiffin. Inside the school compound, they would talk together and play until the clanging bell called them to their classes. The boys would enter the building, skipping through the halls, running up and down the stairs, coming out to the wide front veranda on the second floor, until their teachers gathered them all before their wooden desks and benches for lessons in math, science, history, geography, and their own Vaiṣṇava religion and culture.

| | Mutty Lall era una escuela de niños fundada en 1842 por un rico Vaiṣṇava suvarṇa-vaṇik. El edificio era de piedra, de dos pisos, estaba rodeado por un muro de piedra. Los maestros eran indios y los estudiantes bengalíes de familias locales suvarṇa-vaṇik. Vestidos con sus dhotīs y kurtās, los niños dejaban a sus padres y madres por la mañana y caminaban juntos en pequeños grupos, cada niño cargando unos cuantos libros y su almuerzo. Dentro del recinto de la escuela, hablaban y jugaban hasta que el sonido de la campana los llamaba a sus clases. Los niños entraban al edificio, saltaban por los pasillos, subían y bajaban corriendo las escaleras, salían a la amplia terraza delantera en el segundo piso, hasta que sus maestros los reunían a todos delante de sus escritorios y bancas de madera para las lecciones de matemáticas, ciencias, historia, geografía y su propia religión y cultura vaiṣṇava.

|  | Classes were disciplined and formal. Each long bench held four boys, who shared a common desk, with four inkwells. If a boy were naughty his teacher would order him to “stand up on the bench.” A Bengali reader the boys studied was the well-known Folk Tales of Bengal, a collection of traditional Bengali folk tales, stories a grandmother would tell local children – tales of witches, ghosts, Tantric spirits, talking animals, saintly brāhmaṇas (or sometimes wicked ones), heroic warriors, thieves, princes, princesses, spiritual renunciation, and virtuous marriage.

| | Las clases eran disciplinadas y formales. Cada banca larga albergaba a cuatro niños, que compartían un escritorio común, con cuatro tinteros. Si un niño era travieso, su maestro le ordenaría que “se pusiera de pie en la banca”. Un libro de lectura bengalí que estudiaron los niños era el conocido Folk Tales of Bengal, una colección de cuentos tradicionales bengalíes, historias que una abuela les contaba a los niños locales: cuentos de brujas, fantasmas, espíritus tántricos, animales que hablan, brāhmaṇas santos (o, a veces, algunos malvados), guerreros heroicos, ladrones, príncipes, princesas, renuncia espiritual y matrimonio virtuoso.

|  | In their daily walks to and from school, Abhay and his friends came to recognize, at least from their childish viewpoint, all the people who regularly appeared in the Calcutta streets: their British superiors traveling about, usually in horse-drawn carriages; the hackney drivers; the bhaṅgīs, who cleaned the streets with straw brooms; and even the local pickpockets and prostitutes who stood on the street corners.

| | En sus caminatas diarias hacia y desde la escuela, Abhay y sus amigos llegaron a reconocer, al menos desde su punto de vista infantil, a todas las personas que aparecían regularmente en las calles de Calcuta: sus superiores británicos viajando, generalmente en carruajes tirados por caballos; los conductores de coches de alquiler; los bhaṅgīs, que limpiaban las calles con escobas de paja; e incluso los carteristas y prostitutas locales que se paraban en las esquinas de las calles.

|  | Abhay turned ten the same year the rails were laid for the electric tram on Harrison Road. He watched the workers lay the tracks, and when he first saw the trolley car’s rod touching the overhead wire, it amazed him. He daydreamed of getting a stick, touching the wire himself, and running along by electricity. Although electric power was new in Calcutta and not widespread (only the wealthy could afford it in their homes), along with the electric tram came new electric streetlights – carbon-arc lamps – replacing the old gaslights. Abhay and his friends used to go down the street looking on the ground for the old, used carbon tips, which the maintenance man would leave behind. When Abhay saw his first gramophone box, he thought an electric man or a ghost was inside the box singing.

| | Abhay cumplió diez años el mismo año en que se colocaron los rieles del tranvía eléctrico en la Calle Harrison. Observó a los trabajadores colocar las vías, cuando vio por primera vez que la varilla del tranvía tocaba el cable aéreo, se quedó asombrado. Soñaba despierto con conseguir un palo, tocar él mismo el cable y correr por la electricidad. Aunque la energía eléctrica era nueva en Calcuta y no estaba muy extendida (solo los ricos podían pagarla en sus hogares), junto con el tranvía eléctrico llegaron nuevas farolas eléctricas (lámparas de arco de carbón) que reemplazaron a las viejas luces de gas. Abhay y sus amigos solían ir por la calle buscando en el suelo las viejas puntas de carbón usadas, que el hombre de mantenimiento dejaba atrás. Cuando Abhay vio su primera caja de gramófono, pensó que dentro de la caja había un hombre eléctrico o un fantasma cantando.

|  | Abhay liked to ride his bicycle down the busy Calcutta streets. Although when the soccer club had been formed at school he had requested the position of goalie so that he wouldn’t have to run, he was an avid cyclist. A favorite ride was to go south towards Dalhousie Square, with its large fountains spraying water into the air. That was near Raj Bhavan, the viceroy’s mansion, which Abhay could glimpse through the gates. Riding further south, he would pass through the open arches of the Maidan, Calcutta’s main public park, with its beautiful green flat land spanning out towards Chowranghī and the stately buildings and trees of the British quarter. The park also had exciting places to cycle past: the racetrack, Fort William, the stadium. The Maidan bordered the Ganges (known locally as the Hooghly), and sometimes Abhay would cycle home along its shores. Here he saw numerous bathing ghāṭas, with stone steps leading down into the Ganges and often with temples at the top of the steps. There was the burning ghāṭa, where bodies were cremated, and, close to his home, a pontoon bridge that crossed the river into the city of Howrah.

| | A Abhay le gustaba andar en bicicleta por las concurridas calles de Calcuta. Aunque cuando se formó el club de fútbol en el colegio solicitó el puesto de portero para no tener que correr, era un ávido ciclista. Uno de sus paseos favoritos era ir hacia el sur, hacia la Plaza Dalhousie, con sus grandes fuentes que arrojaban agua al aire. Eso está cerca de Raj Bhavan, la mansión del virrey, que Abhay podía vislumbrar a través de las puertas. Cabalgando más al sur, pasaba a través de los arcos abiertos de Maidan, el principal parque público de Calcuta, con su hermoso terreno verde y llano que se extiende hacia Chowranghī y los majestuosos edificios y árboles del barrio británico. El parque también tenía lugares emocionantes para pasar en bicicleta: la pista de carreras, el Fuerte William, el estadio. El Maidan bordeaba el Ganges (conocido localmente como el Hooghly), a veces, Abhay volvía a casa en bicicleta a lo largo de sus orillas. Allí vio numerosos ghāṭas para bañarse, con escalones de piedra que conducen al Ganges y a menudo, con templos en la parte superior de los escalones. Estaba el ghāṭa en llamas, donde se incineraban los cuerpos y cerca de su casa, había un puente de pontones que cruzaba el río hacia la ciudad de Howrah.

|  | At age twelve, though it made no deep impression on him, Abhay was initiated by a professional guru. The guru told him about his own master, a great yogī, who had once asked him, What do you want to eat?

| | A los doce años, aunque no le causó una gran impresión, Abhay fue iniciado por un guru profesional. El guru le habló de su propio maestro, un gran yogi, que una vez le preguntó: ¿Qué quieres comer?

|  | Abhay’s family guru had replied, Fresh pomegranates from Afghanistan.

| | El guru de la familia de Abhay respondió: Granadas frescas de Afganistán.

|  | All right, the yogī had replied. Go into the next room. And there he had found a branch of pomegranates, ripe as if freshly taken from the tree. A yogī who came to see Abhay’s father said that he had once sat down with his own master and touched him and had then been transported within moments to the city of Dvārakā by yogic power.

| | Muy bien, respondió el yogī. Pasa a la habitación de al lado. Y allí encontró una rama de granada, madura como recién arrancada del árbol. Un yogī que vino a ver al padre de Abhay dijo que una vez se sentó con su propio maestro, lo tocó y luego fue transportado en unos instntes a la ciudad de Dvārakā por su poder yóguico.

|  | Gour Mohan did not have a high opinion of Bengal’s growing number of so-called sādhus – the nondevotional impersonalist philosophers, the demigod worshipers, the gāñjā smokers, the beggars – but he was so charitable that he would invite the charlatans into his home. Every day Abhay saw many so-called sādhus, as well as some who were genuine, coming to eat in his home as guests of his father, and from their words and activities Abhay became aware of many things, including the existence of yogic powers. At a circus he and his father once saw a yogī tied up hand and foot and put into a bag. The bag was sealed and put into a box, which was then locked and sealed, but still the man came out. Abhay, however, did not give these things much importance compared with the devotional activities his father had taught him, his worship of Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa, and his observance of Ratha-yātrā.

| | Gour Mohan no tenía una positiva opinión del creciente número de los llamados sādhus de Bengala (los filósofos impersonalistas no devotos, los adoradores de los semidioses, los fumadores de gāñjā, los mendigos), pero era tan caritativo que invitaba a los charlatanes a su casa. Todos los días, Abhay vio a muchos de los llamados sādhus, así como a algunos que eran genuinos, que venían a comer a su casa como invitados de su padre, por sus palabras y actividades, Abhay se dio cuenta de muchas cosas, incluida la existencia de poderes yóguicos. En un circo, él y su padre vieron una vez a un yogī atado de pies y manos y metido en una bolsa. La bolsa fue sellada y puesta en una caja, que luego fue cerrada con llave y sellada, pero aun así el hombre salió. Sin embargo Abhay no le dio mucha importancia a estas cosas en comparación con las actividades devocionales que su padre le enseñó, su adoración de Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa y su observancia del Ratha-yātrā.

|  | Hindus and Muslims lived peacefully together in Calcutta, and it was not unusual for them to attend one another’s social and religious functions. They had their differences, but there had always been harmony. So when trouble started, Abhay’s family understood it to be due to political agitation by the British. Abhay was about thirteen years old when the first Hindu-Muslim riot broke out. He did not understand exactly what it was, but somehow he found himself in the middle of it.

| | Hindúes y musulmanes vivían juntos en paz en Calcuta y no era raro que asistieran a las funciones sociales y religiosas de los demás. Tenían sus diferencias, pero siempre hubo armonía. Entonces, cuando comenzaron los problemas, la familia de Abhay entendió que se debía a la agitación política de los británicos. Abhay tenía unos trece años cuando estalló el primer conflicto hindú-musulmán. No entendía exactamente qué era, pero de alguna manera se encontró en medio de eso.

|  | Śrīla Prabhupāda: All around our neighborhood on Harrison Road were Muhammadans. The Mullik house and our house were respectable; otherwise, it was surrounded by what is called kasbā and bastī. So the riot was there, and I had gone to play. I did not know that the riot had taken place in Market Square. I was coming home, and one of my class friends said, “Don’t go to your house. That side is rioting now.”

| | Śrīla Prabhupāda: Por todo nuestro vecindario en la Calle Harrison Road había mahometanos. La casa Mullik y nuestra casa eran respetables; del otro lado, estaba rodeado por lo que se llama kasbā y bastī. Entonces el conflicto estaba ahí, yo había ido a jugar. No sabía que el motín estaba ocurriendo en la Plaza Market. Regresaba a casa y uno de mis compañeros de clase dijo: “No vayas a tu casa. Ese lado se está rebelando ahora”.

|  | We lived in the Muhammadan quarter, and the fighting between the two parties was going on. But I thought maybe it was something like two guṇḍās [hoodlums] fighting. I had seen one guṇḍā once stabbing another guṇḍā, and I had seen pickpockets. They were our neighbor-men. So I thought it was like that: this is going on.

| | Vivíamos en el barrio mahometano, la lucha entre las dos partes continuaba. Pero pensé que tal vez era algo así como dos guṇḍās [matones] peleando. Una vez ví a un guṇḍā apuñalar a otro guṇḍā, también había visto carteristas. Eran nuestros vecinos. Así que pensé que era así: esto está pasando.